|

Native

Lincolnite publishes article on Lincoln's political rhetoric Native

Lincolnite publishes article on Lincoln's political rhetoric

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[May 08, 2014]

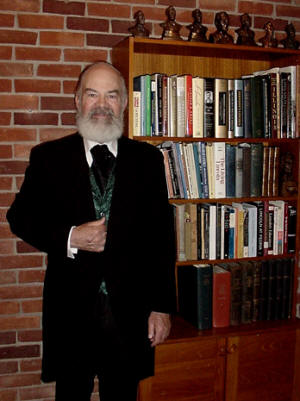

SPRINGFIELD, MO - The lead article in

the recently published issue of the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln

Association (JALA) is an 11,000-word composition by D. Leigh Henson,

professor emeritus of English at Missouri State University. The

title of the article is ďClassical Rhetoric as a Lens for Reading

the Key Speeches of Lincolnís Political Rise, 1852Ė1856.Ē JALA ďis

the only journal devoted exclusively to Lincoln scholarship.Ē JALA,

published twice a year by the University of Illinois Press, selects

only a few article submissions, and articles published have been

revised by their authors according to critiques provided by several

anonymous scholars. Henson, a native of Lincoln, Illinois, attended

Lincoln College and earned undergraduate and graduate degrees in

English at Illinois State University.

|

|

Hensonís article discusses communicative elements in several of

Lincolnís speeches just before, during, and after he began his

celebrated, second political career in 1854. Lincoln returned to

politics after his undistinguished one term in Congress ended in

1849, so that he could oppose efforts to expand slavery into new

territories and the free states. Lincolnís return to politics

involved him in helping to establish the Illinois Republican Party

in 1856. His party leadership in turn led to the 1858

Lincoln-Douglas debates, then to his 1860 presidential election. Hensonís article discusses communicative elements in several of

Lincolnís speeches just before, during, and after he began his

celebrated, second political career in 1854. Lincoln returned to

politics after his undistinguished one term in Congress ended in

1849, so that he could oppose efforts to expand slavery into new

territories and the free states. Lincolnís return to politics

involved him in helping to establish the Illinois Republican Party

in 1856. His party leadership in turn led to the 1858

Lincoln-Douglas debates, then to his 1860 presidential election.

The communicative elements Henson discusses in Lincolnís speeches

derive from classical rhetoricóthe work of Greek and Roman writers

who established the field of study dealing with the theory,

practice, and instruction of discourse. Henson explains that

familiarity with classical rhetoric enables readers to gain a better

understanding of how Lincoln adapted the content, organization, and

style of his speeches to suit his political purposes and audiences.

Some of Lincolnís key speeches of this period refute Senator Stephen

A. Douglasís position that local governments in new territories

should decide whether to allow slavery. Lincoln argued that slavery

is a national, not a local, problem. Lincoln found the solution to

slavery grounded in the principle of the Declaration of Independence

that ďall men are created equal.Ē Lincoln insisted that slavery

should be confined to Southern states, where the Constitution

allowed it and where it would eventually die out. Lincolnís

political rhetoric benefited from his lawyerly ability to expose

contradictions and fallacies in his adversariesí positions.

This article pays special attention to Lincolnís strategies of

organizing his arguments. Henson explains that Lincolnís two-hour,

1854 Peoria address is a textbook example of how to organize a

political speech according to classical rhetoric. Lincolnís

subsequent speeches of this period demonstrate flexible use of

classical organization to suit his message and audience. These

speeches were the first indication of Lincolnís growing

communicative power that enabled him to advance to the White House.

His presidential writing eventually distinguished him as a statesman

and world-renowned man of letters.

This article also explores sources of classical rhetoric that may

have influenced Lincolnís communicative knowledge and skill during

his life-long efforts of self-education. Those sources include

textbooks and anthologies he read in his youth and the speeches he

later studied of Senator Daniel Webster, whose formal education

included the study of classical rhetoric. Henson also notes that

todayís students continue to study rhetoric as an academic field to

help them analyze, evaluate, and create written and spoken

discourse, including communication on the job. He maintains that

this study benefits from the use of writing models with traits

derived from classical rhetoric.

Henson is a fourth-generation link in a chain of historians and

Lincoln buffs from Logan County, Illinois, who passed their interest

in Abraham Lincoln to the next generation. As a student at Jefferson

School in the early 1950s, Henson heard stories of the Lincoln

legend told by E.H. Lukenbill, county superintendent of public

instruction. Hensonís interest in Abraham Lincoln further stems from

a course he took as a freshman at Lincoln College in 1960Ė61. That

course on Lincolnís life and times was taught by the renowned

historian James T. Hickey. For many years Hickey was the curator of

the Lincoln Collection at the Illinois State Historical Library, now

the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. Hickey was a

protťgť of Judge Lawrence B. Stringer, author of the encyclopedic

History of Logan County, Illinois, 1911. It features a chapter on

Abraham Lincolnís legal and political activity in central Illinois

that has been cited by major Lincoln biographers. Stringer drew upon

the friendship and reminiscence of Robert B. Latham, one of the

three founding fathers of Lincoln, Illinois (1853)óthe first

namesake town. Abraham Lincoln was the attorney for the townís

founders, and the town was founded before he became famous. Latham

was also a founder of Lincoln University, now Lincoln College.

Latham was a personal and political friend of Abraham Lincoln and a

Union colonel in the Civil War. Stringer was the first major

benefactor of the newly relocated and enhanced Lincoln Heritage

Museum of Lincoln College.

[to top of second column] |

The Lincolnian seed that Lukenbill and Hickey planted in

Hensonís education lay dormant for forty years. It did not

germinate until after he had completed his formal education at

Illinois State University, had taught high school English for

thirty years in Pekin, Illinois, and was well into his

fourteen-year career of teaching technical communication at

Missouri State University. In 2004 the Illinois State Historical

Society gave a Superior Achievement Award to Hensonís community

history website of Lincoln, Illinois. In 2008Ė09 he was a member

of the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission of that town. He

researched and wrote the play script for the 2008 re-enactment

of the 1858 Republican rally in Lincoln the day after the last

Lincoln-Douglas debate. Lincoln delivered a stump speech at the

rally, but no copy of it has been found. Hensonís play script

features a ďreasonable facsimileĒ of that speech and rally,

including give-and-take with the audience. The re-enactment was

accomplished through collaboration with Paul Beaver, professor

emeritus of history at Lincoln College; Ron Keller, director of

the Lincoln Heritage Museum; and Wanda Lee Rohlfs, civic leader.

In 2008 Henson proposed erecting a statue of Abraham Lincoln the

1858 Senate candidate and a corresponding historical marker,

both to be installed on the lawn of the Logan County Courthouse,

where the 1858 rally took place. Presently a local committee is

raising funds for those purposes. In 2012 Hensonís book titled

The Town Lincoln Warned: The Living Namesake History of Lincoln,

Illinois, received a Superior Achievement Award from the

Illinois State Historical Society. In 2013 he proposed several

additional statues of Lincoln in Lincoln to expand its namesake

heritage, strengthen civic pride, and increase heritage tourism.

Also in 2013 the Lincoln Elementary School District #27 honored

Henson as one of four distinguished alumni. Henson continues to

research Lincolnís political rhetoric.

Henson is an elected member of the Society of Midland Authors.

He is also a member of the Illinois Center for the Book, an

affiliate of the Library of Congress. He shares information

about his Abraham Lincoln research, Illinois history, historic

preservation, and heritage tourism on social media at Facebook

and LinkedIn. His LinkedIn site has links to his various online

publications: http://la.linkedin.com/pub/d-leigh-henson/16/1a5/923.

Access the JALA website at

http://www.abrahamlincolnassociation.org/Journal.aspx. JALA

publishes its articles online six months after they appear in

print. Access an overview and pictorial supplement to Hensonís

article about Lincolnís rhetoric at

http://findinglincolnillinois.com/dlhjalaarticle.html.

[Text received; D. LEIGH HENSON,

Ph.D.]

|