|

The Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) has been slowly making its way into

the Midwest from the Eastern United States. In 2014, Logan County

was officially added to the EAB quarantine list along with Sangamon

and Menard Counties. According to Scott Schirmer with the Illinois

Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Environmental Programs, in the

city of Lincoln four EAB traps were set last year, and of the four,

three resulted in collecting the undesirable insect. The Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) has been slowly making its way into

the Midwest from the Eastern United States. In 2014, Logan County

was officially added to the EAB quarantine list along with Sangamon

and Menard Counties. According to Scott Schirmer with the Illinois

Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Environmental Programs, in the

city of Lincoln four EAB traps were set last year, and of the four,

three resulted in collecting the undesirable insect.

The meeting Thursday was hosted by the University of Illinois

Extension Educator Jennifer Fishburn. Guest speakers included

Schirmer, Aaron Schulz; a Certified Arborist with King Tree

Specialists, Inc. from Tremont, and Reinee Hildebrandt, a State

Urban Forester for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

Jennifer Fishburn, Universtiy of Illinois Extension Educator for

Logan, Menard and Sangamon Counties

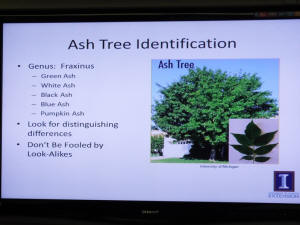

Fishburn began the morning talking about tree identification. She

noted that there are several species of tree that have strong

similarities to the vulnerable ashes, and there are also ash tree

classifications that are not affected by EAB.

Fishburn said that

folks should not automatically assume they have it. She said, often,

the first step is to figure out for sure if a tree is a vulnerable

Ash species. She said, for example, the Mountain Ash tree is not a

true Ash tree. Fishburn said the trees that may be affected are the

Green Ash, White Ash, Black Ash, and Blue Ash. In this area, most of

the true Ash trees will be either Green or White.

She talked about identifying the tree in winter with no foliage as

well as in the summer when the trees are leafed out.

In looking at a defoliated tree, look for a compound leaf stem. On a

twig from the tree, there will be bud scales. She said the bud scale

on the Green Ash will look like capital letter “D” turned on its

side. The White Ash bud scale will appear to look more like a grin

or smiley face.

When the trees are leafed out, the leaf will be in a cluster of

seven with three sets being directly across from one another and a

single leaf on the tip.

The bark of the Ash tree will be light and have somewhat of a

diamond shape texture.

Fishburn also pointed out the varieties of “look-alike’s” that often

confuse homeowners. She said trees such as Shagbark Hickory, Pecan,

Mountain Ash, Dogwood, and Chestnut are often mistaken for Ash

trees.

Scott Schirmer with the Illinois Department of Agriculture’s

Bureau of Environmental Programs

Scott Schirmer was the next speaker of the morning. He said that to

date, ash tree deaths in the United States is exceeding 350 million.

In Illinois, approximately 290 communities have been identified as

having an EAB presence. Currently, the scope of the infestation in

the U.S. includes a geographical area eastward from New York State

to Iowa and southward from Michigan to Tennessee.

Schrimer explained that the EAB is an Asian insect that has come

across the ocean through various exported items. He said that part

of the problem is that the Asian countries don’t do as good a job of

monitoring the wood products they use for pallets and shipping

materials. A number of insect species have entered the United States

by that means. He warned that there would certainly be more in the

future. He also noted that the Eastern European countries are more

careful than Asian countries, and the U.S. sees fewer problems from

that part of the world.

Once the insects make their way to the U.S., they search out living

trees in which to take up residency. A chain reaction or cycle then

begins where that the insects spread across an area via domestic

wood products such as firewood.

Schrimer discussed the role of the Illinois Department of

Agriculture’s role in monitoring the EAB. He said that the USDA

identifies the situation as an EAB Emergency Program. The components

of the emergency program include surveying and identifying the

presence of the EAB. The agency is responsible for quarantining

affected areas and monitoring quarantine compliance. The USDA also

provides community education and outreach as well as doing research

on the control and eventual eradication of the EAB.

He spoke of identifying a problem through the typical “D” shaped

openings going into a tree and noted that these are hard to find.

Other symptoms of EAB will more than likely be noticed before the

“D”, and also after it is too late to do much to save the tree.

The EAB causes its damage by burrowing under the bark of the Ash

tree where it lays its eggs for the next generation. It is the

larvae that do the actual damage by eating the layer under the bark

that transfers nutrients from the root system to the upper portions

of the tree. The larvae travel upward in a snaking pattern that

interrupts the nutrient transfer.

Schrimer said that it would take a large infestation of the EAB to

cause significant damage. He said 10, 20, or even 30 individual

larvae won’t kill a tree, which is why early detection is the most

important aspect of saving a tree.

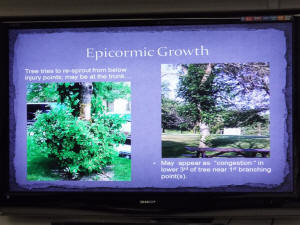

Schrimer pointed out some signs that a tree is in trouble. One

significant indicator is Epicormic Growth. In that scenario, the

tree will try to save itself by growing branches and leafing out

below the EAB damage on the truck. Another significant sign is

woodpecker damage. He said woodpeckers will go in search of the

larvae that they know is there. The result is, they will completely

peck apart the trunk of a tree.

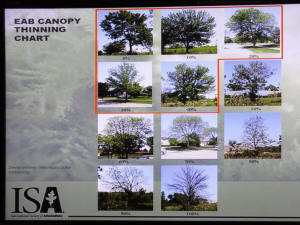

And finally the tree will tell you it is in trouble through

reduction of the leaf canopy. Schrimer said the reduction of the

canopy will begin at the top and spread downward in most all cases.

He offered a slide showing reduction of the canopy by percentages, 0

through 100. He told the group that trees with 10, 20, 30, or even

40 percent reduction can still be saved. When the reduction reaches

50 percent or more, he said the best action would be to fell the

tree and replace it.

[to top of second column] |

He also cautioned that when one is trying to determine

whether or not to save or destroy, consideration has to be given

not only to the cost of each solution, but also to public

safety. With several members of the Lincoln Street Department

on hand, Schrimer said that as the damage spreads, a tree will

become brittle. Because of this, branches will break and fall

easily, there are perils for workers in trying to trim the dead

material from the trees, and catastrophes can happen.

Addressing the city staff, Schrimer said that it is very important

for municipalities to have tree inventory records. He showed

examples of inventory records. On the records, he identified the

tree species, its location, and its condition. He uses a ranking

system to help him know what stage of life the tree is in with a

class 1.0 being a newly planted young tree to class 5.0 being a

mature, but dead tree that needs removed.

It was also suggested that a municipality use a wide variety of tree

species with population percentages on any one variety not exceed 10

percent or so.

He noted that EAB is not the first tree killer to come into the

United States, and it will not be the last. He said there are other

threats right now that will more than likely eventually become an

issue in the Midwest. He specifically named the European Gypsy Moth

and Asian Gypsy Moth that prey on Oak trees and the Gold Spotted Oak

Borer, which he said was the "EAB of the Oak."

Aaron Schulz, Certified Arborist with King Tree Specialists, Inc.

Aaron Schulz was the third speaker. He discussed means of

controlling EAB through the use of pesticides. As a professional who

specializes in this area, he talked primarily about professional

grade insecticides and how they are applied.

Like Schrimer, he cautioned that there is a point when treatment is

not the best answer. Using the same slide Schrimer used, he told the

group that he would not treat a tree that has exceeded 40 percent

canopy loss.

Also, when considering treatment or removal, cost is going to be a

factor he said. The products, Schulz spoke about the most, were

Xytect, Safari, and Tree-age. The products are applied either as a

drench at the base of the tree, soil drench or an injection into the

trunk collar.

To determine the treatment cost; the tree is measured in diameter at

4.5 feet above the soil level. This measurement is then identified

as the “DBH.” Pesticide treatment can cost between $6 and $12/one

inch DBH depending on the type of treatment.

Removal of a tree includes a number of costs, from cutting and

removal to stump removal and depending on the size of the tree can

be very costly. Schulz said that for younger trees that have less

than 40 percent EAB damage, annual or bi-annual treatments can be

administered for a number of years before the cost would exceed the

cost of removal.

Reinee Hildebrandt, a State Urban Forester for the Illinois

Department of Natural Resources

Reinee Hildebrandt was the final speaker of the day. As a member of

the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, she was representing

the Tree City USA certification program. She noted that the city of

Lincoln is already a Tree City and applauded the city for the

investment it makes each year in sustaining its urban forest.

She noted that the city of Lincoln spends $5.41 per capita on its

urban forest. She said the figure is well above national figures but

below the state average. She too talked about the importance of

having a tree inventory and also of having a wide variety of trees

in that forest.

She suggested that the city create a volunteer tree board to assist

in the inventory and management of the tree population. She also

noted that the city's tree ordinance may need to be tweaked a bit.

She specifically suggested that the ordinance not name the trees

that are allowed or not allowed within city limits.

Currently, the city ordinance has a short list of approved for

planting and a list of forbidden trees. Hildebrandt said the city

should remove those conditions and replace it with “for a list

contact the city forestry department.” She said this would give the

forestry department the opportunity to amend the list as needed

without having to go through the time and expense of amending the

ordinance.

Finally, she talked about grant and other funding opportunities to

help support the cost of EAB control. She suggested that there are

grants available through the IDNR as well as a private corporation

called Treefund.org. She said that the Illinois Financial Authority

has low-interest loans available. She also suggested soliciting

local groups and clubs such as garden clubs, 4-H and Boy Scouts. She

noted that an urban forest project could be a great one for a Scout

working toward Eagle status.

During the discussion period, one of the most significant questions

came from the Lincoln Street Department and pertained to disposal of

the trees once they are cut.

Once cut, it is safe to run the trees through a wood chipper for

mulch, and it is also acceptable to burn the trees.

Another question: Once a tree is cut, how long would it take the

insects to move out of the tree and into another?

The answer: When the tree is cut with the insect in its larvae

stage, it cannot move. Eggs are laid in the fall, so if trees are

cut and destroyed in the late fall, there would be no opportunity

for the insect to escape to another tree.

[Nila Smith]

The University of Illinois has a vast

amount of information, including illustrations, to assist homeowners

in identifying EAB in their landscapes. To view the website follow

this link:

http://web.extension.illinois.edu/firewood/eab.cfm

Past related

article

Emerald Ash Borer Found In Logan, Menard, and Sangamon Counties

By John Fulton |