|

In December, Illinois Farm

Bureau President Richard Guebert discussed NAFTA in his presidential

address. He noted that the desire to update the current agreement

was “understandable and commendable,” but said, “Complete

withdrawal from NAFTA would decimate Illinois farmers as well as

rural America.” In December, Illinois Farm

Bureau President Richard Guebert discussed NAFTA in his presidential

address. He noted that the desire to update the current agreement

was “understandable and commendable,” but said, “Complete

withdrawal from NAFTA would decimate Illinois farmers as well as

rural America.”

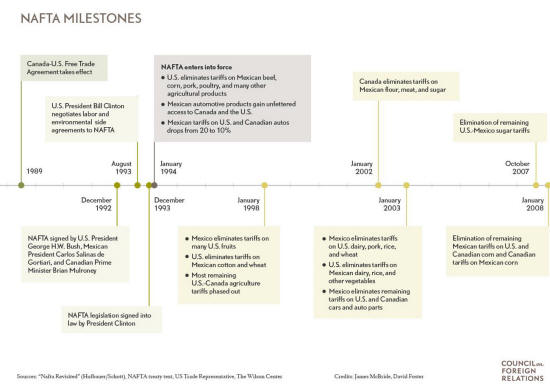

The NAFTA agreement of today originated in 1994, and was put into

place gradually over the next 14 years. In 2008, the plan was

considered to be fully implemented, and its design was intended to

benefit the U.S. and Canada, but to also improve the economic status

in Mexico.

The theory, according to an

article published on the Council on Foreign Relations website by

James McBride and Mohammed Aly Sergie, the agreement was to improve

the economy in Mexico, provide new job opportunities in that

country, and thus reduce the number of Mexican citizens immigrating

into the United States. This was to be accomplished by implementing

free trade between the three countries without tariffs, which would

increase Mexico’s manufacturing industry and make their exports more

competitive in the marketplace.

However, opponents of NAFTA argue that the impact was just the

opposite. Because the agreement lifted tariffs on imports into

Mexico, the United Sates had a new customer for its products,

including agricultural products. The purchase of corn and soybeans

from the United States resulted in the drop of agricultural

production and Ag jobs in Mexico. Thus, Mexican farm workers

continued to cross the borders in order to find work, perhaps more

so than before NAFTA.

Prior to NAFTA, the United States and Canada had a two-party trade

agreement, so there was speculation that NAFTA would not do anything

to improve trade between those two countries. However, the results

belied speculation. After NAFTA, Canada to U.S. export dollars rose

from $110 billion to $346 billion annually, and U.S. to Canada

exports rose at about the same amount. What NAFTA was supposed to do

for Canada though hasn’t exactly worked out. The goal had been to

increase the productivity gap between the two countries and increase

jobs for Canadian’s. However, Canada’s productivity rate remains at

72 percent of the United States.

The NAFTA may have had the greatest impact on the U.S. economy, with

an estimated increase in exports by about $80 billion per year. It

also produced more export related jobs, approximately 200,000, and

an increase in the average pay levels of these jobs.

However, the downside to the NAFTA agreement was the absence of

tariffs and taxes that made it easier for U.S. manufacturers to

relocate to Mexico where labor was cheaper, thus making the profits

for those individual companies higher, without incurring any cost

for returning goods back to the U.S. for distribution.

The biggest down side to this is that now, U.S. blue collar workers

are losing jobs to Mexico, and the country is becoming lopsided with

the best employment opportunities to those with higher-education;

those without education are becoming a big portion of the nation’s

unemployment statistics.

In the article McBride and Sergie state, “The U.S.-Mexico trade

balance swung from a $1.7 billion U.S. surplus in 1993 to a $54

billion deficit by 2014. Economists like the Center for Economic and

Policy Research’s (CEPR) Dean Baker and the Economic Policy

Institute argue that this surge of imports caused the loss of up to

600,000 U.S. jobs over two decades, though they admit that some of

this import growth would likely have happened even without NAFTA.”

From January to the first

portion of March 2018, NAFTA seemed to be a hot topic in Washington,

with explosive tweets from the President that he would imposes taxes

on cars if Mexico put tariffs on steel and aluminum. The President

has even threatened to dissolve NAFTA altogether. But House Ways and

Means Chairman Kevin Brady says that is not going to happen. On

March 6th Brady said that there was good progress being made on

NAFTA, and that the United States would not “scrap NAFTA.”

Since that time there has been little said about NAFTA, and it

appears that the president has turned his attention on China and

imposing tariffs there on goods sold to the United States.

So what is to become of NAFTA? Writer for the Council on Foreign

Relations Shannon K. O'Neil says the agreement has some specific

timelines to meet IF it is to be changed.

[to top of second column] |

O’Neil notes, “On July 1, Mexican citizens will elect a new

president and more than 3,000 officials, including every member of

the House of Representatives, a third of the senators and eight

governors. In this highly contested set of races, the economic model

of the last 30 years, of which NAFTA is an integral part, is in

effect on trial.

That makes the timing of any announced compromise on NAFTA tricky. A

resolution before the election opens the ruling Institutional

Revolutionary Party and its presidential candidate Jose Antonio

Meade (lagging third in the polls) to broadsides from every

direction, with every other aspirant sure to boast they could have

gotten a better deal. Trump will aid these critiques, undoubtedly

crowing about his huge win over Mexico, a country that until he came

along was ‘killing us on jobs and trade.’”

Even if the agreement would come to pass before the Mexico election,

then there is the possibility, even probability that the entire

process and progress made thus far will be scrapped and negotiations

would begin again with a new set of lawmakers in Mexico.

If that does happen, no one can even guess how long it might take to

re-negotiate the re-negotiations. BUT….O’Neil speculates that NAFTA,

could drag out long enough that Trump and his opposing candidates

could use the agreement as a portion of the 2020 presidential

election platforms.

O’Neil offers the following explanation:

Even if today’s Mexican negotiating team

approves a new NAFTA, tomorrow’s Mexican Congress may not. A July

announcement all but pushes the ratification in Mexico to this new

body, which will take its seats September 1 (followed by the

President’s inauguration three months later). A victory by current

front-runner Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, a leftist who has already

called on the government to stop negotiations and wait for

(presumably his) new administration, could make the new legislature

less likely to rubber stamp any agreement reached by the preceding

administration.

A July announcement also runs into the U.S. electoral calendar.

Under current Trade Promotion Authority (which needs to be renewed

in July), after reaching an accord U.S. negotiators need to wait

least 90 days before officially signing. This waiting period is

extended to 180 days if negotiators have made changes to how trade

remedies work (which is likely). Then, before bringing it to a vote

in the Congress, they need to wait up to another 105 days for an

International Trade Commission study on the effects on the U.S.

economy. That would put passage in the hands of a new Congress -

which could be Democratic, at least in the House.

If the original NAFTA fights are any guide, a Democratic-led House

would require significant changes before approving a Trump-led bill,

pushing passage deep into 2019. And in the face of Democratic

opposition, Trump himself might want to keep the NAFTA drama going,

using it as a platform for his 2020 reelection campaign.

O’Neil’s article wraps up with a summation that after all the talks,

all the working groups, and the thousands of hours invested, the end

result may very well be nothing. She adds that what does go right in

this scenario is that those who benefit from the current NAFTA may

stand up and defend it more vigorously than in the past when the

agreement was not in the foreground of politics.

She offers the best conclusion saying, “But what all the talks and

tensions have done is to rally NAFTA's once passive beneficiaries to

its cause. Which means that NAFTA, whether old or new, will likely

continue,” and U.S. grain sales to Mexico will continue.

[Nila Smith]

NAFTA's Biggest Challenge May Come After the

Deal

NAFTA’s Economic Impact

IFB members re-emphasize support of NAFTA

FarmWeekNow.com

|