|

Struebing is a Master Gardener and Master Naturalist

and knows the land of central Illinois.

Logan County is at

the heart of the tall grass prairie in Illinois.

“Illinois is known as the prairie state, but not

everyone knows where that name came from,” said Struebing. When the

first French traveled to Illinois in the 16th and 17th centuries,

they saw a landscape that is very different from what we see today.

Those explorers saw a seeming ocean of tall grass waving in the wind

when they first arrived, like the waves on the sea. There were no

trees in central Illinois on the very flat land. The word prairie is

a French word to describe the illusion of waves that stretched

before them.

But what created this topography?

The glacial period of the earth when the mountains of ice moved

south out of what is now Canada created the very flat areas of

Illinois. The massive weight of the Wisconsin and Illinois glaciers

moving forward and back as they grew and melted scraped the land

flat creating our current landscape.

The glaciers also ground up the rock in their way and created

gravel. When the glaciers retreated, they left a flat land in most

of Illinois. It is easy to see where the glaciers ended their march

south. The descending land between Atlanta and Lincoln marks the

so-called terminal moraine of the Wisconsin glacier, the farthest

south it traveled. The descent of topography on Interstate 155 near

Delavan is the end of the Illinois glacier. The result of glacial

movement was the flat land covered with crushed rock. The Illinois

glacier moved the farthest south of the two.

Once the glaciers retreated north, melting because of the warming

climate, there were some spruce trees left in their wake. The land

was a sort of tundra, or frozen ground.

The next change to occur was wind from the west blowing fine silt

into the area. This silt was called loess and created the rich soil

in central Illinois, covering the gravel sometimes to a depth of 200

feet.

As the climate warmed, the spruce trees died out and the first of

the grasses started to grow on this flat land, between eight and ten

thousand years ago.

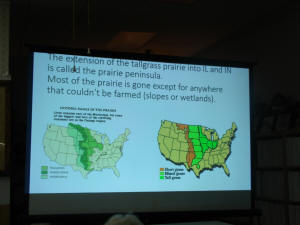

The center of the United States was once a sea of prairie grass from

Ohio to a swath of states extending from Canada to Texas.

Because of rain fall totals, Illinois, Indiana and

Ohio had the tallest of the grasses growing on their land. The

states west of Illinois had shorter grasses, while the grass in

Nebraska and Kansas was shorter yet, due to reduced rainfall.

At one time, Illinois had twenty-two million acres of grassland

within its borders. Only a fraction of that remains today. The rich

soil, plentiful rain, and frequent fires were the perfect

environment for growing these grasses, sometimes reaching heights of

eight feet.

[to top of second column] |

Huge herds of buffalo tilled the land with their

wanderings, adding to the factors that produced the perfect

environment. “There were ten kinds of grasses and thirty types of

flowering grasses. The most common tall grasses in the so-called

prairie peninsula were Big Blue Stem and Indian Grass,” said

Struebing. When the first explorers arrived this is what they saw,

the waving grasses that resembled ocean waves, and they named it

prairie.

They also found a land of deep rich soil that was

very difficult to farm. The grasses had deep roots that bound the

soil together.

The land was also very wet, a remnant of the tundra left by the

glaciers and the warming climate.

The biography of Illinois now gives way to technology. An inventor

named John Deere developed a plow with a sharp smooth metal blade

that tore through the soil, and a creative Irishman named Scully

came up with a way to drain the land.

The waving grasses of the prairie gave way to the waving corn fields

we see today.

The grass prairie is gone

forever, but it had many benefits for the environment.

“There are spots of tall grasses in old cemeteries

and along old railroad right-of-way, but the conditions that created

thousands of years of grasslands in Illinois are gone forever. Only

one tenth of one percent of the original millions of acres of

grassland remains,” said Struebing.

So the history of Illinois has left us with several benefits that we

still enjoy today. The Illinois and Mississippi Rivers are gouged

out remnants of the retreating glaciers. The deep bedrock of gravel

provides building material. The water flowing through the gravel

that is sometimes hundreds of feet deep provides clean drinking

water for millions of people.

And the soil in central Illinois, the rich deep soil provides the

best farming resource in the world.

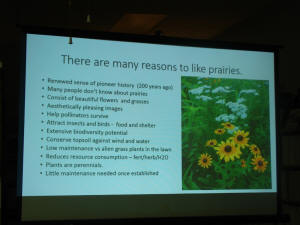

Jim Struebing is passionate about the prairie and what it provided

during its existence. “The factors involved in the development of

the tall grass prairie can no longer be replicated, but there is

something people can do to honor this part of Illinois’ history. I

have several small plots of prairie grasses in my yard and some

flowering prairie grass,” he said. Anyone can have a small piece of

Illinois history in their yard. And the state of Illinois has

discovered the benefits of slow growing prairie grass. The sides of

interstates are seeded with it and now require less mowing.

The flora of Illinois’ early biography can still be with us.

The Logan County Genealogical and Historical Society meets the third

Monday of each month at their research facility across from the

newly remodeled Lincoln Depot at 6:30 p.m. The public is invited to

attend, and they always have an interesting and informative

presentation.

[Curtis Fox] |