|

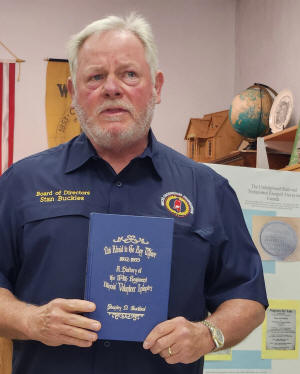

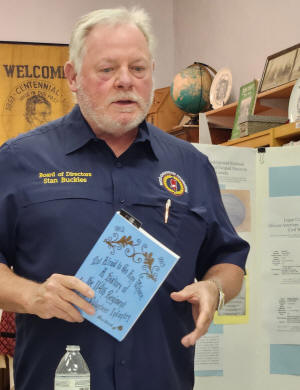

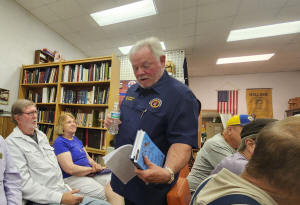

LCGHS members hear about the 114th

Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War

[June 20, 2025]

At the June 16 Logan County

Genealogical and Historical Society meeting, the program was about

Civil War soldiers from Logan County. Stan Buckles of Mt. Pulaski

presented the program.

LCGHS program chair Marla Blair introduced Buckles, who wrote a book

called Not Afraid to go Anywhere. 1862-1865. A History of the 114th

Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry. Blair said the book talks

about Logan County men who became soldiers and fought in the Civil

War.

As Buckles started his

presentation, he asked if anyone there was a Civil War buff. A few

people nodded their heads. Buckles’ interest in the Civil War began

when he was ten and visited Vicksburg, Gettysburg and other Civil

War sites.

When Buckles started college, he first went to Bradley University

then transferred to Millikin University where he got a degree in

history. He has worked for the Department of Conservation as an

interpreter, at Mt. Pulaski Courthouse and at Postville Courthouse.

In 1979, Buckles joined the reactivated regiment to get a feel for

what the average soldier did, what they ate, what they carried and

things like that.

Buckles always wanted to write a book but was not thinking about

regiment history. He was actually researching to write a biography

of John A. Mclernen, but someone else beat him to that.

Therefore, Buckles began

researching the 114th regiment. Reactivations of the regiment

started in 1969. Tuesday nights during the summer, the group does a

flag lowering ceremony at Lincoln’s tomb. Buckles said they are the

only group in the country who does anything like it.

2019 was the 50th anniversary of the reactivated regiment and

Buckles discovered nothing special had been planned. He found out

most of the reenactors knew nothing about the original regiment.

In just eight months, Buckles

researched and wrote a book about the 114th regiment. He

self-published, which took a lot of work. Buckles only published 200

copies of the first edition. He said they are almost sold out, but

can be found at Books on the Square.

For the second edition, Buckles did

a paperback copy, added an index and made some minor corrections.

After the book was first published, Buckles said people contacted

him and said they have pictures and letters from family members who

were in the regiment. Unfortunately, not many of the regiment’s

letters survive.

The 114th (Sangamo) regiment was

formed in September 1862 when Abraham Lincoln called for an

additional 500,000 troops. Members of the regiment were from

Sangamon, Cass, Menard and Logan Counties. Buckles said Logan County

had fewer in the regiment than the other counties. Many from Logan

County joined the 106th Regiment under Colonel Robert Latham and did

not see much action.

James W, Judy, an auctioneer from Tallulah, was the Colonel of the

regiment but resigned after they fought in Vicksburg. Buckles said

Judy was fighting both the Confederacy and the U.S. War Department.

Colonel Judy had to pay for his men’s food and lodging to get to

Camp Butler and tried to get reimbursed. An attorney told Judy to

contact the war department and file a claim.

Unfortunately, Buckles said what Judy did was not the proper

procedure. Judy should have gone to Governor Richard Yates and

fought that way. The U.S. War Department not only held Judy’s pay

but also were taking him to court for trying to bilk the U.S.

government.

As Judy tried to get everything straightened on, he talked to Grant,

Sherman and Ralph Bucklin from Ohio, but Buckles said none of them

could get anything done. Finally, in 1867, Judy was compensated.

Lieutenant Colonel John F. King from Clearlake was the next officer

to lead the regiment. King was a competent man, but Buckles said he

was sick quite a bit.

Something Buckles learned as he did research was that not everyone

who fought for the Union was a friend of Abraham Lincoln. Many in

the regiment knew Lincoln personally, but did not agree with

Lincoln’s politics. Several of the soldiers were Democrats.

There was one man from Springfield named John Gibson who hated

Lincoln with a passion. Buckles said Gibson was fighting the war to

put down the confederacy and wanted nothing to do with freeing the

slaves.

Gibson spoke strongly against the Emancipation Proclamation and

Lincoln. Buckles read one of Gibson’s angrily worded statements that

was filled with swearing. Gibson wanted to get out of the service

and did not even care if he was dishonorably discharged.

Buckles said Private Gersham Greening and another buddy heard

Gibson’s diatribe and reported what Gibson said to Lieutenant

Colonel King. Others refused to serve with Gibson.

King filed charges and went all the way up the ranks to General

[William T.] Sherman, who said the officer needed to learn to keep

their mouths shut whether they agree with what the president said or

did. Sherman said when you work with the army, you do what we tell

you and keep your mouths shut.

Gibson was placed in solitary

confinement in a tent until after the Vicksburg Campaign. Buckles

said Grant then convened a court martial. Gibson was stripped of his

rank and dishonorably discharged.

Most who did not agree with the Emancipation Proclamation often just

left. Buckles said some soldiers went to find those who left and

brought the deserters back in chains. Some rejoined the regiment and

got an honorable discharge after coming up with a believable story.

Buckles said others did hard labor at the military prison in Alton.

The Battle at Vicksburg was baptism by fire for the regiment though

they performed well there. Buckles said Brice’s Crossroads was a

“whole different animal.”

Sherman was beginning his march to Atlanta and did not want

[Confederate Major General Nathan Bedford] Forrest getting on his

supply lines and busting up his railroad.

Therefore, Sherman picked fellow West Pointer [Brigadier General]

Samuel Sturgis to lead the expedition. Buckles said Sturgis did well

at Fredericksburg and was at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek after

General Lion was killed. Sturgis and John Scofield helped manage the

retreat decently.

Buckles said the problem with Sturgis was that he was an alcoholic

who was drinking and carousing at a hotel in Memphis the night

before the regiment was to leave.

Another leader named Colonel William McMillen was also drunk. The

next morning, two of McMillen’s aides had to hold him up. Buckles

said the aides had to take McMillen to a house to sober up before

leading the troops to Atlanta.

Benjamin Grierson of Jacksonville led the cavalry, but Buckles said

Grierson hated Sturgis with a passion. Grierson was a raider and not

a fighter. Buckles said when Grierson had a grudge, he stuck his

head in the sand and ignored problems.

[to top of second column] |

The 114th regiment

marched to the Mobile and Ohio Railroad to tear it up. Buckles

said when General [Robert E.] Lee got wind of it, he told the

regiment to get the men to Tupelo, Mississippi.

It took the regiment

ten days to for the Union infantry and cavalry to march down to

Brice’s Crossroads. Buckles said there was about 8500 troops

altogether.

The battle was doomed from the beginning. Buckles said the infantry

started marching from the camps around Lagrange, Tennessee. The

skies opened up and it started pouring. From Tennessee on, there was

rain every day. For eight days, the men had to walk in mud that was

sometimes knee deep. Buckles said they were losing their brogans

[boots] in the mud and some were barefoot. Some had so much mud on

their wool pants that the men cut them off so they could walk.

The temperatures were in the 90s and

humidity was 100 percent. Buckles said these men were dying as they

were marching.

Forrest planned a strategy, which Buckles said was West Point to a

T. Forrest sucked the men in to Brice’s Crossroads, saying he was

going to get their cavalry and take them out. It stirred Sturgis’

troops up to move faster. The soldiers ran on the muddy roads about

three to five miles from the battlefield. Some fell off on the side

the road and others were dying of heatstroke. Buckles said the

regiment lost a quarter of its men.

Grierson showed up and Buckles said the infantry tried to save the

day. King was told by the drunk McMillen not to shoot the guys in

front of them because they were Union Cavalry pot shotting with

Confederate Cavalry.

It turns out the information was not true. Buckles said the men

looked like Union soldiers because Confederates had stolen Union

uniforms and put them on. Because Sturgis’ soldiers were being shot

at, they wanted to shoot back. Finally, Sturgis told his men to fire

at will.

Forrest told the men to flank the enemy, but Buckles said thick

foliage hid their enemies. Fortunately, the enemies’ dark uniforms

were visible.

When King retreated to Brice’s Crossroads, Buckles said it was utter

chaos as other units fell back for the same reason. There was smoke,

humidity, yelling, screaming and artillery going off and there was

utter confusion.

McMillen rides up to King and told King to hold the Crossroads at

all cost, so King planted the color guard right in the middle of the

crossroads.

The men were surrounded by confederate soldiers and cavalry. Buckles

said one of King’s captains said if they stayed five minutes longer,

they would be going up. King started to order the retreat, but the

color guard did not hear when they were told to retreat.

The color guard stood at the crossroads and Buckles said it was

literally them against the Confederate Army. The regiment still had

soldiers on their left and their right.

Finally, Gershom Greening realized they were the only unit there.

The men were getting shot at, the flag was getting riddled and the

uniforms had bullet holes in them. Buckles said the guy to

Greening’s left took a bullet and went down, so Greening decided to

get out of there. Sturgis led the retreat to Memphis and the men

were furious.

Buckles said Sturgis’s favorite

line was if Mr. Forrest will leave me alone, I will leave him alone.

Forrest continued to dog the men until Collierville, which is near

Memphis.

Though it had taken ten days to get there, Buckles said it took the

men just two days to get back. A lot of the 114th were captured. The

regiment ended up splitting at Ripley, Mississippi with part of them

following King and others following the column.

The 114th Regiment was in the first division under Alexander Wilkin,

formerly a colonel in Minnesota. Buckles called Wilkin a brilliant

man who decided not to go with “the rest of those idiots” and

instead took their own route back.

It was a good thing they took a different route, because Buckles

said they probably would not have survived otherwise. The group tied

in with two other "colored" units, the 55th and the 59th USCT and

they covered the rear. He said the black soldiers changed a lot the

minds of the 114th. Though the 114th had not wanted anything to do

with those units until then, without those units, the 114th would

not have made it back.

John Meyer, a 114th Regiment member from Mt. Pulaski, had once hired

Abraham Lincoln as an attorney to settle some business. Buckles has

photos of Meyer and would love to know more about him.

Buckle’s dad was a boy scout, and boys would call Meyer Uncle

Johnny. Meyer would sit on the square and tell the boys he survived

at Andersonville after being captured at Brice’s Crossroad. Meyer

said, “the reason I survived is because I always boiled my water

before I drank it and I always cooked my food before I ate it.”

Buckles said Meyer was transferred out of Andersonville when the

Confederates thought he was dying and was sent to the Naval hospital

in Annapolis, Maryland.

When Meyer got home, he weighed under 98 pounds and his own mother

carried him up the lane. Buckles said Meyer appears to have been the

last survivor of the 114th Regiment and also the last Mt. Pulaski

resident to personally know Abraham Lincoln. Meyer died in 1940 at

age 99.

Something Buckles works with is an organization called the Brice’s

Crossroads Foundation. The group put up a monument at Brice’s

Crossroads to honor the 114th Regiment. They later put up monuments

to honor all the Illinois regiments who fought shoulder to shoulder

in the area.

Eventually, Buckles said the foundation hopes to get artillery

pieces put in. The foundation published a battlefield guide with

maps of how the battle progressed. Buckles said the foundation is

getting help from other organizations in Mississippi. He thinks it

could soon be the premier battlefield site.

Once Buckles had finished his presentation, he asked if anyone had

questions.

LCGHS member Diane Farmer asked if

there was a directory of regiment members and whether they were all

from the area. She wondered if her great great grandfather was in

the regiment.

Buckles said there is an Adjutant General’s Report has an online

directory, though it is not completely accurate. No one from the

regiment appears to have been from Lincoln. He said it was not

likely that her ancestor was in the regiment, but was probably in

the 72nd or 117th Regiment.

LCGHS member Tom Larson asked whether there are archives available

In Washington, D.C.

Though there are archives available, Buckles said it is costly to

get access to them. You have to make reservations to get in to see

the archives.

LCGHS President Bill Donath said the National Park Service has a

registry of the 114th Regiment you can find online.

Next, there was a question about how far south the Illinois troops

got.

Buckles said the troops got to Nashville, Vicksburg and Mobile.

Because of their illustrious service, A.J. Smith made the 114th

pontoniers and took them off the front lines. The regiment had heavy

casualties in Nashville. There is a monument to them on Shy’s Hill.

LCGHS member Curt Fox asked about the original point of the battle

[at Brice’s Crossroads].

Buckles said they wanted to keep Forrest off of Sherman’s supply

lines by keeping him occupied. The troops accomplished it, but not

the way they had planned.

After the war, Buckles said Sturgis tried to become head of a

soldiers’ home in Washington, D.C. A physician from the 72nd in Ohio

who heard about it was livid and convinced people to write letters

to keep Sturgis from getting the position. King wrote about seeing

Sturgis sitting on a porch with a bottle of whiskey on the table as

the men were loading their muskets and getting ready to go into

battle.

John Meacham, originally from New

Holland said he had a distant relative in the 114th Regiment who

died of wounds he received at Nashville. Meacham has some of the

relative’s letters and showed them to Buckles.

In July, Blair said Jeff Salsberry, manager of the David Davis

Mansion in Bloomington will be speaking. David Davis was a judge and

good friend of Abraham Lincoln. Next month’s meeting will be Monday,

July 21 at 6:30 in the LCGHS building.

[Angela Reiners]

|