|

Mich. Arborist Looks to Clone Redwoods Mich. Arborist Looks to Clone Redwoods

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[November 01, 2007]

SAN GERONIMO, Calif. (AP) -- When David Milarch first visited Northern California in 1968, he thought he would see avenues of coast redwoods

100 miles long. What he found instead, he said, was a "moonscape."

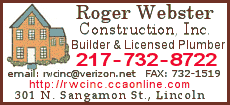

[Caption: David Milarch, co-founder

of the Champion Tree Project, looks over the first cutting taken

from a 1,000-year-old redwood tree at Roy's Redwoods Open Space

Preserve in San Geronimo, Calif., on Tuesday. Expert

tree climbers went up three 1,000-year-old redwoods over 250-feet

tall to collect genetic samples that will be used to create clones

of the ancient trees which will be used to begin to re-establish old

growth redwood forests around California. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)]

|

|

Nearly 40 years later, the Michigan arborist has returned to the region to realize his dream of preserving and restoring the most ancient of these trees using the latest advances in genetic cloning. Nearly 40 years later, the Michigan arborist has returned to the region to realize his dream of preserving and restoring the most ancient of these trees using the latest advances in genetic cloning.

On a foggy Tuesday in Marin County about 25 miles north of San Francisco, Milarch assembled a team of crack tree climbers who used ropes and harnesses to clamber more than

100 feet into the treetops at Roy's Redwoods Preserve.

The workers clipped boughs from some of the preserve's oldest and tallest trees to get genetically pure samples of some of nature's ultimate survivors.

Milarch, 58, said he believes these trees can provide the toughest possible stock for a kind of "genetic savings account" he hopes can be used to restore old-growth redwoods in their native range up and down the state. About 95 percent of the original forest has been cut down over the last few hundred years.

"What does this tree's immune system have in it that it has survived when other trees haven't?" Milarch said, leaning against the massive, shaggy trunk of a redwood he's dubbed "Grandma," which he estimates is at least 800 years old.

David Milarch is co-founder of the Champion Tree Project, based in Copemish, Mich.

He and son Jared created the nonprofit in 1996 to preserve the genetics of what they say are "the last great trees of America."

Average mature redwoods stand between 200 to 240 feet tall and have diameters of

10 to 15 feet. The tallest trees have been measured at more than 370 feet, making coast redwoods the tallest living organisms in the world. The hardiest members of the species can live to be 2,000 years old.

Redwoods have gained a prized status among nature lovers rivaled only by a few other marquee animal species like the panda and the blue whale. But their high-quality timber has also long been favored by home builders seeking the same durability that allows the trees to survive so stubbornly in the wild, which has led to widespread harvesting.

As co-founder of the Champion Tree Project, Milarch has devoted the past

10 years of his life to collecting buds from so-called "champion trees"

-- the tallest, largest and oldest specimens of individual species. He also has taken samples from historic trees found on the estates of Teddy Roosevelt and George Washington.

But Milarch calls redwoods a special case. Because coast redwoods can reproduce themselves through a natural cloning process as well as by mating with other trees, a tree like Grandma could effectively be the latest incarnation of an individual tree that first saw daylight 20,000 years ago, Milarch said.

"If we're going to pick out the strongest, longest-lived genetics, this old gal's a survivor," he said.

Horticulturists and genetic engineers plan to use the samples from the Marin County redwoods to see which of several techniques

-- some traditional, some cutting-edge -- works best to reproduce the trees. Milarch has high hopes for the most advanced approach, known as tissue culturing, which creates exact genetic replicas by manipulating individual cells.

[to top of second column] |

Not everyone agrees that cloning represents the most effective way to preserve redwoods. Conservation groups have traditionally focused on curbing development and logging along the 500-mile stretch from Big Sur to the Oregon border where most coast redwoods grow.

"Protecting the habitat of the species in place -- I think that's the most important approach to conservation," said Deborah Rogers, a redwood geneticist and director of conservation science for the San Diego County-based Center for Natural Lands Management.

According to Rogers, a genetic storehouse that could protect the entire species from an unforeseen cataclysm caused by climate change or an imported disease would require samples from hundreds of trees across the state.

Still, she said, any push to protect redwoods has an important ecological ripple effect.

"When we conserve redwoods in nature, we're sweeping species that don't have any hope of celebrity status along with them," Rogers said.

Milarch hopes that samples from about 20 individual trees taken from ancient redwood stands in five distinct areas will be enough to get his restoration effort under way. Next he plans to solicit landowners and communities for plots of at least five acres where the clones will be planted and, ideally, interbreed.

Even if the cloning plan fails to produce the sweeping stands of towering conifers Milarch envisioned in his younger days, at least one scientist believes more in-depth study of ancient redwood genes could yield discoveries that go beyond trees.

Bill Libby, a professor emeritus of forestry at the University of California, Berkeley, has studied redwoods for 50 years and was one of the first scientists to probe redwood genetics. He joined Milarch on the dimly lit forest floor to observe the project, which he called "darn interesting."

The way trees mature has a lot in common with how humans mature, Libby said. Understanding redwood longevity could offer insight into the human aging process, as well, he said: "There may be real scientific gold here."

___

On the Web:

Champion Tree Project: http://www.championtrees.org/

[Associated Press; By MARCUS WOHLSEN]

Copyright 2007 The Associated Press.

All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast,

rewritten or redistributed.

|