|

Other

News... sponsored by Richardson Repair & A-Plus Flooring |

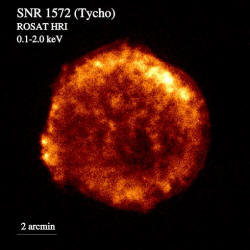

Study illuminates star explosion from 16th century

Study illuminates star explosion from 16th century

[December 04, 2008]

NEW YORK (AP)

--

It's no big surprise. Scientists have known the light came from a supernova, a huge star explosion. But what kind of supernova?

|

A new study confirms that, as expected, it was the common kind that involves the thermonuclear explosion of a white dwarf star with a nearby companion. The research, which analyzed a "light echo" from the long-ago event, is presented in Thursday's issue of the journal Nature by scientists in Germany, Japan and the Netherlands. The story of what's commonly called Tycho's supernova began on Nov. 11, 1572, when Brahe was astonished to see what he thought was a brilliant new star in the constellation Cassiopeia. The light eventually became as bright as Venus and could be seen for two weeks in broad daylight. After 16 months, it disappeared. Working before telescopes were invented, Brahe documented with precision that unlike the moon and the planets, the light's position didn't move in relation to the stars. That meant it lay far beyond the moon. That was a shock to the contemporary view that the distant heavens were perfect and unchanging. The event inspired Brahe to commit himself further to studying the stars, launching a career of meticulous observations that helped lay the foundations of early modern astronomy, said Michael Shank, a professor of the history of science at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The direct light from the supernova swept past Earth long ago. But some of it struck dust clouds in deep space, causing them to brighten. That "light echo" was still observable, and the new study was based on analyzing the wavelengths of light from that. ___ On the Net: Nature: http://www.nature.com/nature/ |