|

Qatar's recruited athletes stir debate on citizenship

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[August 25, 2016]

By Tom Finn [August 25, 2016]

By Tom Finn

DOHA (Reuters) - When 39 athletes from

Qatar qualified for the Rio Olympics, the most in the tiny Gulf

state's history, Noor al-Shalaby celebrated the achievement in a

Facebook post.

"Qatar! You are in my blood and my soul," wrote the 34-year-old

accountant.

The small team delivered the country's first silver medal at the Rio

Olympics.

And the Olympians - at least 23 of whom were born outside Qatar and

brought in to help the country flourish athletically - are a source

of pride for Egyptian-born Shalaby, who was raised in Qatar.

But their status is also a reminder of restrictive citizenship laws

that have complicated Shalaby's life and made her future uncertain.

Qatar has for years used its immense oil and gas wealth to recruit

sportspeople from around the world, part of an ambitious vault onto

the world sporting stage by the wealthy Arab state which will host

the soccer World Cup in 2022.

Kenyan runners and Bulgarian weightlifters granted citizenship to

compete internationally for Qatar are compared by outsiders to

'mercenaries' sent to win medals for Doha and promote its standing

abroad.

But the practice of handing passports to these athletes has stirred

a debate about national identity inside Qatar where residents like

Shalaby who have lived in the country for decades, and whose

expertise may be needed in a post-oil economy, have no obvious path

to citizenship.

"I was born in Doha... my friends are Qatari and, in my heart, I am

too." she said. "Of course it hurts that I am not a citizen."

LAWS 'OUTDATED'

The influx of foreigners into the once-impoverished Gulf states goes

back to the discovery of oil in the 1930s.

The growth of hydrocarbon industries brought in thousands of Arab

workers, including Syrians and Palestinians, to bolster small local

populations.

Many secured jobs and settled in the Gulf among local Sunni Muslim

populations who had traditionally lived in the desert or in small

coastal towns, living off pearling and trade.

But as numbers of foreign residents rose and millions of South Asian

laborers were brought in to power construction booms, tightly-knit

Gulf populations saw demographic change as a threat to their way of

life.

Attuned to this, Gulf authorities have kept heavily guarded rights

to nationality.

Qatar, a former backwater that is the world's largest LNG exporter,

is home to a vast foreign population that ranges from low-paid

construction laborers living in camps outside cities to top

executives who receive generous tax-free salaries.

No legal provisions exist allowing foreigners, who account for

around 90% of Qatar's 2.3 million population, to become permanent

residents.

Instead a handful of foreigners who must speak Arabic and have

resided in the country for at least 25 consecutive years are

absorbed into Qatar’s citizenry on a case by case basis that

requires approval from the emir.

A Qatar government spokesperson was not immediately available to

comment. Officials, including the former emir, Sheikh Hamad bin

Khalifa al-Thani, have said nationality is given to people who apply

and fulfill regulations.

[to top of second column] |

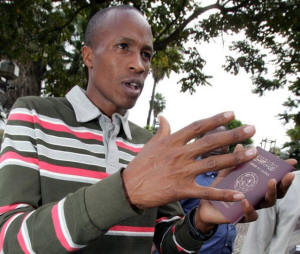

Saif Saaeed Shaheen, Qatar's 3,000 metres steeplechase world

champion, speaks to the media in Kenya's capital Nairobi September

20, 2006. REUTERS/Antony Njuguna/File Photo

"ADDING VALUE"

But some younger Qataris are now questioning the laws controlling

citizenship, calling them outdated.

"If these guys [athletes] get naturalized then what about doctors,

scientists, engineers, academics and artists? Don't they add more

value to society?," Hamad al-Khater, a public sector employee,

tweeted after the Olympic debut of Qatar's handball team, 11 out of

14 of whom are naturalized athletes.

A prominent Emirati commentator argued in a 2013 op-ed for

citizenship to be opened to long-time foreign residents including

entrepreneurs, scientists and academics who have contributed to

society.

But many remain deeply apprehensive about relaxing citizenship laws:

they fear the added expense - Qatar spends billions of dollars each

year on free education, healthcare, and housing loans for its

estimated 300,000 citizens - and question whether naturalized

citizens could ever become true Qataris.

"Even without naturalizing people, our identity is in a kind of

crisis. Giving out passports would complicate things," said

businessman Abdullah al-Mohannadi, 32.

There is concern too that foreigners might have an adverse influence

on Qatar's dynastic political system and conservative culture -

based on deep-rooted tribal values that are already considered under

threat.

"What happens down the line when these individuals and their

descendants call for change and go against Qatar’s political

stability?" said Faisal al-Shadi, a Lebanese student born in Qatar.

"These citizens might come together and challenge the status quo".

After growth peaks and Qatar moves toward a post-oil economy,

analysts say, the economic rationale for restricting citizenship

could change.

"Qatar will need to attract long-term residents who can contribute

to the tax base and support what will eventually become an aging

population," said a Doha-based university lecturer.

"Residency rights are one way to entice professionals to stay in the

country for longer."

(Editing by William Maclean and Richard Balmforth)

[© 2016 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

Copyright 2016 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed. |