|

After a perilous journey to Europe, a

young migrant learns his fate

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[December 30, 2016]

By Selam Gebrekidan [December 30, 2016]

By Selam Gebrekidan

TOREKOV, Sweden (Reuters) - For more than a

year, Girmay Mehari dreaded his 18th birthday next February.

The teenager escaped from an Eritrean jail two years ago after he was

sentenced to an indefinite term for evading national service or plotting

to escape the country. The police never spelled out the charges.

With money his brothers raised in New York and Israel, Girmay smuggled

himself across the border, traveled thousands of miles through the

Sahara, and made it across the Mediterranean to Italy.

He arrived in Malmo, Sweden's third largest city, in September 2015, one

of nearly 35,000 migrant children to settle alone in Sweden that year.

In many ways, the luck that buoyed him through his grueling journey has

endured.

He arrived in Sweden just before Europe's borders slammed shut. Today,

he lives with 10 other children in a quiet village called Torekov, in a

villa that was once a bed & breakfast. Nearby are the pristine Swedish

beaches immortalized in Ingmar Bergman's film, "The Seventh Seal."

The scars on Girmay's skin, from illness and torture he endured in

Libya, have largely faded. He has grown about 4 centimeters (1.5 inches)

in 12 months and has put on weight, thanks to the Coke he guzzles

throughout the day. He has dyed the top of his hair a flaming red and

learned a bit of Swedish. But his future long remained uncertain.

When he turns 18 in late February, he will become an adult in the eyes

of Swedish law. That change of status, Girmay thought, could hurt his

chances of getting asylum.

"I don't have any regrets about coming here," he said in September. "But

I would love Sweden a lot more if I had my papers."

Questions kept him up at night. Would he be forced to move to an adult

shelter? Could he continue to go to school? And most worrying, would the

slow slog of his asylum application grind to a halt the day he becomes

an adult?

Girmay was not alone. Uncertainty pervades the lives of most migrants.

So many people have sought asylum in Western Europe in recent years that

even the most welcoming nations, like Sweden, have tightened their

rules.

Nearly two-thirds of the unaccompanied children who came to Sweden in

2015 are still awaiting a decision from the government, according to

data from the Swedish Migration Agency. The median asylum-processing

time for unaccompanied minors from Afghanistan, Syria and Eritrea –

three of the largest groups seeking refuge in Sweden – has increased to

nine months in 2016 from under six months in 2015.

The Swedish government says it tries to prioritize cases like Girmay's,

where the applicant is about to turn 18. But the results have fallen far

short of the goal because of a large increase in the number of

applications and complexities of individual cases, said Linn Nilson, a

spokeswoman for the Migration Agency.

In Girmay's case, a year elapsed between his first intake interview and

a second, more probing one that decided the outcome of his asylum

request.

FROM MILAN TO MALMO

Girmay arrived in Sweden when the refugee crisis was convulsing Europe.

As many as 153,000 refugees, about a tenth of them unaccompanied

children, arrived on Italy's shores last year. Girmay was one of them.

When a rescue boat brought him to Messina, on the northeastern tip of

Sicily, in early September, Girmay was emaciated. He had not had a

decent meal for months, he said. Sores had erupted on his body from the

scabies he contracted in a Libyan jail.

[to top of second column] |

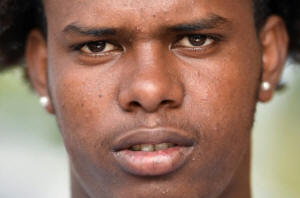

Eritrean migrant Girmay Mehari poses for a photograph in Bastad,

Sweden, September 9, 2016. Picture taken September 9, 2016.

REUTERS/Fabian Bimmer

Italian authorities brought him to a refugee camp in Verona for

treatment, Girmay said. But worried he would be forcibly

fingerprinted, he snuck out of the camp with his friend. That day,

the two teenagers ran into a Nigerian woman who took them in, fed

them, and lent them her phone.

Girmay called his older brother, Habtay, in Tel Aviv, who then

reached out to another brother, Tesfom, in Albany, New York. The

older siblings told Girmay to take a local train to Milan. He spent

the next week at a shelter near Milan's central train station,

recuperating and preparing for the last leg of his journey.

In Milan, Habtay sent Girmay 750 euros ($780) through a hawala

money-transfer agent. Girmay used the money to buy a pair of jeans,

a sweatshirt, a Nokia phone, a SIM card and a train ticket for

Munich, Germany.

German immigration officers checked him into a hospital in Munich

but Girmay says they let him leave when he insisted on heading north

to Sweden. He spent a night in Frankfurt before heading to Malmo,

from where he called his mum for the first time in five months.

"My mother did not believe my brothers when they told her I was

alive," he said. "She didn't trust that I could cross all of these

miles by myself." Reuters was not able to reach Girmay's mother.

NEW LIFE

Girmay has come a long way since then. He moved to Torekov a year

ago. He goes to school in Bastad, a wealthy resort town that hosts

the Swedish Tennis Open every summer. He says he has a lot of

catching up to do. He takes a few hours of maths, geography and

history at the junior high school but spends most of the school day

in intensive language classes. The local government looks after his

needs and he gets a 700 crown ($76) stipend every month.

At night, he uses his Macbook Air, a loan from the school district,

to watch Youtube videos of Swedish and English lessons. He plays

soccer video games with his roommates and watches American rap

videos. Wiz Khalifa is a favorite.

"I learned so much after I became a refugee," Girmay said. "If you

stay in your village ... you won't understand what the world is

about, what society is about. But once you leave, you're determined

to make it ... You want to extend your horizon as much as you can."

In late December, Girmay received an envelope from the Swedish

Migration Agency. Inside was a pink card that granted him the right

to live and work in Sweden for the next five years. The wait was

finally over.

(Edited by Alessandra Galloni and Simon Robinson)

[© 2016 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

Copyright 2016 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed. |