|

Hate speech seeps into U.S. mainstream

amid bitter campaign

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[November 08, 2016]

By Peter Eisler [November 08, 2016]

By Peter Eisler

KOKOMO, Indiana (Reuters) - The lettering

is crude, scrawled in black spray paint on the sidewalk in front of

Karen Peters’ neatly kept home in the quiet, working class neighborhood

where she’s lived most of her life. But the contempt is clear.

"KKK Bitch.”

The racially charged graffiti appeared in mid-October on cars, homes and

telephone poles in the small city of Kokomo, Indiana. Many victims, like

Peters, were African American, though some were not. Many also had lawn

signs for Democratic candidates in this week’s presidential election,

and the signs at several homes were painted over with the Ku Klux Klan’s

notorious initials.

“I think it’s a political thing; it’s getting out of hand,” said Peters,

who believes the heated tenor of the presidential campaign – and

especially the aggressive, nativist rhetoric of Republican candidate

Donald Trump – has emboldened extremists.

“When you have (candidates) saying ignorant things, maybe other people

think it’s ok to do this stuff, and that’s pretty doggone sad ... It

seems like our country is going backwards.”

Police have no suspects in the attacks. Democrats, including the mayor

and local party officials, believe they were politically motivated.

Local Republicans are skeptical, suggesting the damage is the work of

ignorant hooligans with no place in the party.

Across the United States, the inflammatory and confrontational tone of

political rhetoric is creeping into public discourse and polarizing the

electorate.

It’s hard to quantify the impact; there is no national data that tracks

politically motivated crimes or incendiary speech.

However, the percentage of voters who believe insulting political

opponents is “sometimes fair game” has climbed over the campaign season,

from 30 percent in March to 43 percent in October, according to surveys

by the non-partisan Pew Research Center. A majority of voters for both

parties have “very unfavorable” views of the other party – a first since

Pew began asking the question in 1992 – and trust in government is

hovering near all-time lows.

“These indicators reflect inter-group tensions that can translate into

everything from coarse discourse or low levels of aggression all the way

up to extremist acts,” said Brian Levin, director of the Center for the

Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University.

While much of the venom has been aimed at immigrants, African Americans

and other groups typically aligned with Democratic presidential

candidate Hillary Clinton, Republicans also have faced vitriol and

hostility.

Much of the debate over extremism has focused on the so-called

Alt-Right, a loose-knit movement of white nationalists, anti-Semites and

immigration foes that has emerged from the political shadows to align

itself with the Trump campaign.

Trump’s vows to build a wall on the Mexican border, deport millions of

illegal immigrants and scrutinize Muslims for ties to terrorism have

energized the Alt-Right community.

Such rhetoric has helped legitimize the Alt-Right’s concerns about an

erosion of the country’s white, Christian majority, said Michael Hill, a

self-described white supremacist, anti-Semite and xenophobe who heads

the League of the South, a “Southern Nationalist” group dedicated to

creating an independent “white man’s land.”

“The general political climate that sort of surrounds his campaign has

been very fruitful, not only for us, but for other right-wing groups,”

Hill said.

Similar nationalist undercurrents have stirred other countries, from

Russia to Japan to Britain. Last summer, as Britain’s debate over

leaving the European Union reached a fever pitch, Jo Cox, a pro-EU

lawmaker, was shot and stabbed in the street. Murder suspect Thomas Mair

proclaimed “death to traitors, freedom for Britain.”

In the United States, reports of hostile political displays, vandalism

and violence are cropping up regularly.

In Mississippi, a black church was burned and painted with “Vote Trump.”

In North Carolina, a county Republican office was set ablaze last month

and a nearby building spray painted with “Nazi Republicans leave town.”

In Ohio, a truck load of manure was dumped at a Democratic campaign

office. In Utah, a man displaying Trump yard signs found KKK graffiti on

his car. In Wisconsin, a fan at a college football game wore a President

Barack Obama mask with a noose on his neck.

[to top of second column] |

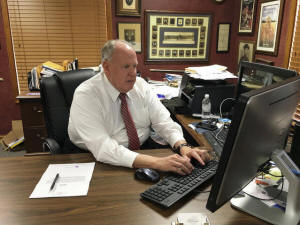

Craig Dunn, Republican party chairman for Howard County, Indiana

works at his desk in Kokomo, Indiana, U.S. November 1, 2016.

REUTERS/Peter Eisler

Neither the Trump nor the Clinton campaigns responded to requests

for comment.

EXTREMISM GOES MAINSTREAM

Trump's positions are consistent with the Alt-Right goal of “slowing

the dispossession of whites,” said Jared Taylor, a white nationalist

whose website, American Renaissance, is a movement favorite. But the

media is over-hyping his support within the Alt-Right “in an attempt

to discredit him,” Taylor added.

Trump has been criticized by both Democrats and some Republicans for

being slow to condemn the more extreme elements of the political

right. But when a leading KKK newspaper ran a pro-Trump story on its

front page last week, his campaign immediately issued a statement

rejecting the “repulsive” article.

Taylor, Hill and other Alt-Right figures say they don’t advocate or

condone vandalism or violence. They dismiss the notion that their

rhetoric constitutes hate speech, arguing that their vilification by

the left is far more hateful.

Left-wing extremists do have a history of aggressive confrontation

with people or groups seen as fascist or racist, says Heidi Beirich,

of the Southern Poverty Law Center, an organization that monitors

extremist movements. “There’s usually more violence from the

anti-racists than the racists,” she said.

The free speech provisions of the U.S. Constitution’s First

Amendment grant broad protections for inflammatory rhetoric. But

state and federal statutes do give law enforcement agencies

authority to investigate and prosecute “hate crimes” motivated by

bias against a race, ethnicity, religion, disability or sexual

orientation.

A 6 percent increase in hate crimes documented last year by the

California State University researchers showed relatively little

underlying change in attacks against most minority groups. But

crimes against Muslims rose 86 percent.

Some who study and work in the political arena believe there has

been a general erosion in civility that began long before the start

of the current presidential race.

Craig Dunn, Republican party chairman for Howard County, Indiana,

which includes Kokomo, says that a minority of extreme voices are

being amplified over the Internet and social media, fueling “a

general breakdown in civility.”

Local officials worry about how their community is being affected.

"The atmosphere is “more volatile, there’s more tension,” said

Kokomo Mayor Greg Goodnight, a Democrat. The graffiti attacks were

deeply troubling, he adds. “I don’t remember anything like this ever

happening here.”

Monica Fowler, 43, who had “KKK” sprayed on her Democratic yard

signs, is struggling with the attacks. “It’s okay to disagree,” she

says. “But if what you’re doing is going to scare or harm another

person, how dare you.”

(This story corrects in the ninth paragraph to state that trust, not

distrust, in government is near all-time lows Note: paragraph 2

contains language that may offend some readers)

(Additional reporting by Tim Reid in Los Angeles and Guy

Faulconbridge in London. Editing by Stuart Grudgings.)

[© 2016 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

Copyright 2016 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

|