|

Column: Can insider

trading case at SCOTUS help Leon Cooperman?

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[September 23, 2016]

By Alison Frankel [September 23, 2016]

By Alison Frankel

NEW YORK (Reuters) - On Oct. 5, the

U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on a question that has

created considerable confusion in lower courts: When the government

claims a corporate outsider has profited from trading illegally on

inside information, what must it prove about the motive of the

insider who supplied the tip?

The Securities and Exchange Commission, meanwhile, just brought its

biggest insider trading case in years, against hedge fund manager

Leon Cooperman of Omega Advisors.

The SEC’s complaint, filed in federal district court in

Philadelphia, accuses the legendary investor of earning about $4

million in illicit profits from trading in Atlas Pipeline Partners

after a corporate insider gave him confidential information about a

big divestiture.

Cooperman has declared his innocence Wednesday in a five-page letter

to investors and a widely reported conference call.

The SEC has framed its case, as I’ll explain, to avoid the question

at the Supreme Court. But I think there is a way Cooperman’s lawyers

at Paul Weiss Rifkind Wharton & Garrison can take advantage of the

case before the justices. My theory takes a bit of explaining, so

first, some background.

ALL IN THE FAMILY

In the case at the Supreme Court, Salman v. U.S., Bassam Salman was

convicted of trading illegally on the basis of information that

originated with a Citigroup investment banker. The banker talked to

his brother about companies in play. His brother, in turn, passed

tips to Salman, who matched his trades to those of the banker’s

brother.

Insider trading law is quirky. Congress has never defined insider

trading in a statute, so the law has been shaped by judges watching

over federal prosecutors and Securities and Exchange Commission

regulators asserting violations of securities fraud statutes.

As the law has developed - most notably in the 1983 Supreme Court

case Dirks v. SEC - to prove insider trading by a corporate

outsider, the government must show that the insider who leaked

confidential information benefited from supplying the tip.

Otherwise, courts have held, there’s no fraud.

In the Salman case, the justices have been asked to decide how

tangible the tipster’s benefit must be. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court

of Appeals, which affirmed Salman’s conviction, held the close

family relationship between the Citi banker and the brother he

tipped is enough to establish the banker’s personal benefit.

The 2nd Circuit suggested in a landmark 2014 decision, U.S. v.

Newman, that the government must prove tipsters received a benefit

“that is objective, consequential, and represents at least a

potential gain of a pecuniary or similarly valuable nature.” The

justices will have to reconcile the two circuit court standards.

MISAPPROPRIATION THEORY

The SEC contends its suit against Cooperman case falls into a

different category than tipster cases. Cooperman, according to the

commission, was the beneficial owner of more than 9 percent of Atlas

Pipeline in 2010. As such, he had much easier access to top

corporate officials than ordinary shareholders, the SEC alleges.

Through the first half of 2010, that access apparently did not give

him much confidence in the company. Cooperman dumped holdings worth

millions of dollars and allegedly told an Omega consultant that

Atlas was a “shitty business.”

In July 2010, however, an Atlas executive allegedly told Cooperman

that the company planned to sell an important operating facility for

more than $700 million. The SEC claims that the unnamed Atlas

official believed Cooperman had an obligation not to use the

information to trade Atlas securities. According to its complaint,

“Cooperman explicitly agreed that he could not and would not use the

confidential information … to trade.”

The SEC, of course, alleges that Cooperman did, in fact, trade on

his advance word of the divestiture, reaping about $4 million in

profits in various Omega funds. The SEC claims Cooperman committed

securities fraud by misappropriating information given to him in

confidence by an insider who trusted him not to use the information

for his own trading.

The U.S. Supreme Court gave its blessing to the government’s

so-called misappropriation theory of insider trading in the 1997

case U.S. v. O’Hagan, when the justices upheld the conviction of a

Dorsey & Whitney lawyer who traded options in a firm client that was

about to place a tender offer. In broad strokes, the

misappropriation theory presumes that corporate insiders are

disclosing confidential information only to those with a duty to

protect the corporation’s secrets.

In those cases, insiders are victims of fraudulent misappropriation

so their personal benefit for supplying confidential information

doesn’t come into play. The government’s burden is to show the

alleged fraudster violated the trust of the corporate insider, not

the trust of the company.

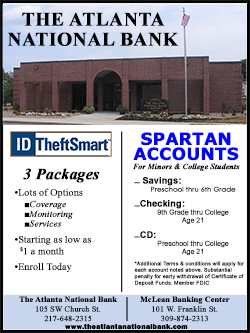

[to top of second column] |

Leon G. Cooperman Chairman, Omega Advisors, speaks on a panel

discussion at the annual Skybridge Alternatives Conference (SALT) in

Las Vegas May 9, 2013. REUTERS/Rick Wilking

The O’Hagan case, of course, involved a lawyer who breached a

fiduciary duty when he traded a client’s securities based on inside

information. The SEC and the Justice Department have also brought

misappropriation cases against defendants with no fiduciary duty to

the insider who disclosed confidential information.

The SEC’s case against billionaire Mark Cuban, for instance, alleged

circumstances very similar to those described in the Cooperman

complaint. Cuban received advance word of a private placement by an

Internet search company in which he held a large stake. Despite

supposedly telling the company he wouldn’t reveal the confidential

information, Cuban sold shares before the offering was announced to

avoid losses when his ownership stake was diluted.

Cuban persuaded the trial judge in his case that he never agreed not

to trade on the basis of the advance tip he received. The case was

dismissed, then revived by the 5th Circuit, which said that Cuban

obtained additional inside information about the private placement

after telling the company he wasn’t going to sell his shares.

Ultimately, a federal jury in Dallas cleared Cuban of wrongdoing.

In the 3rd Circuit, where the SEC filed its case against Cooperman,

the appeals court recently upheld the SEC’s expansive view of who

can be liable under the misappropriation theory. A defendant named

Timothy McGee found out about an impending corporate deal from a

buddy he’d befriended at Alcoholics Anonymous, who confided in McGee

when the stress of the deal led him to start drinking again. McGee

said he owed no duty of confidentiality to his friend, but the 3rd

Circuit affirmed his conviction.

DID ATLAS WANT TO INFLUENCE COOPERMAN?

Believe it or not, all of the preceding is necessary background for

how the Salman case may be useful to Cooperman. We know from the

McGee and Cuban cases that courts (if not juries) are open to the

idea that the government need not show a fiduciary relationship

between a corporate insider and an alleged fraudster who

misappropriates inside information. That’s bad news for Cooperman.

But what if the insider at Atlas tipped Cooperman about the

divestiture to influence the hedge fund manager’s trading in the

company? Remember, Cooperman was dumping shares until he heard about

the planned sale of the facility and I’m sure Atlas executives were

not thrilled about a sell off by the owner of a nearly 10 percent

stake in the company. It’s not unreasonable to wonder if Atlas was

hoping news of the big deal would change Cooperman’s mind about his

stake. (Interestingly, holding onto shares because you’ve gotten a

tip they will rise in value is not securities fraud, which requires

buying or selling securities.)

To be sure, the SEC complaint explicitly said Atlas gave Cooperman

inside information under the proviso that he not use it to trade. I

suspect Cooperman’s lawyers are going to probe exactly what was said

in the conversations between the hedge fund manager and Atlas

insiders.

And if they can show Atlas tipped Cooperman to influence his trading

decisions, then this case could turn on whether the tipper received

a personal benefit from supplying information – the issue before the

Supreme Court in Salman. If the justices come up with a very

restrictive definition of what constitutes a personal benefit for a

tipster, that could help Cooperman.

I know this hypothetical depends on a big pile of ifs but it’s worth

thinking about. It’s also worth a reminder that insider trading law

would be a lot clearer if Congress enacted a statute.

(Reporting by Alison Frankel. Editing by Alessandra Rafferty.)

[© 2016 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2016 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

|