|

Snake on a plane! Don't

panic, it's probably just a (soft) robot

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[June 19, 2017]

By Jeremy Wagstaff [June 19, 2017]

By Jeremy Wagstaff

SINGAPORE

(Reuters) - Robots are getting softer.

Borrowing from nature, some machines now have arms that curl and grip

like an octopus, others wriggle their way inside an airplane engine or

forage underwater to create their own energy.

This is technology that challenges how we think of, and interact with,

the robots of the not-too-distant future.

Robots are big business: by 2020, the industry will have more than

doubled to $188 billion, predicts IDC, a consultancy. But there's still

a lot that today's models can't do, partly because they are mostly made

of rigid metal or plastic.

Softer, lighter and less reliant on external power, future robots could

interact more safely and predictably with humans, go where humans can't,

and do some of the robotic jobs that other robots still can't manage.

A recent academic conference in Singapore showcased the latest advances

in soft robotics, highlighting how far they are moving away from what we

see as traditional robots.

"The theme here," says Nikolaus Correll of Colorado University, "is a

departure from gears, joints and links."

One robot on display was made of origami paper; another resembled a

rolling colostomy bag. They are more likely to move via muscles that

expand and contract through heat or hydraulics than by electricity. Some

combine sensing and movement into the same component - just as our

fingertips react to touch without needing our brain to make a decision.

These ideas are already escaping from the lab.

SMALL, AGILE

Rolls-Royce, for example, is testing a snake-like robot that can worm

its way inside an aircraft engine mounted on the wing, saving the days

it can take to remove the engine, inspect it and put it back.

Of all the technologies Rolls-Royce is exploring to solve this

bottleneck, "this is the killer one," says Oliver Walker-Jones, head of

communications.

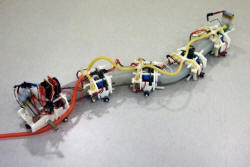

The snake, says its creator, Arnau Garriga Casanovas, is made largely of

pressurized silicone chambers, allowing the controller to propel and

bend it through the engine with bursts of air. Using soft materials, he

says, means it can be small and agile.

For now, much of the commercial action for softer robots is in

logistics, replacing production-line jobs that can't yet be handled by

hard robots.

Food preparation companies and growers like Blue Apron, Plated and

HelloFresh already use soft robotics for handling produce, says Mike

Rocky, of recruiter PrincetonOne.

The challenge, says Cambridge Consultants' Nathan Wrench, is to overcome

the uncertainty when handling something - which humans deal with

unconsciously: figuring out its shape and location and how hard to grip

it, and distinguishing one object from another.

"This is an area robots traditionally can't do, but where (soft robots)

are on the cusp of being able to," said Wrench.

MARINE INSPIRATION

Investors are excited, says Leif Jentoft, co-founder of RightHand

Robotics, because it addresses a major pain point in the logistics

industry. "Ecommerce is growing rapidly and warehouses are struggling to

find enough labor, especially in remote areas where warehouses tend to

be located."

[to top of second column] |

A soft robot designed in the form of a salamander is displayed in

Singapore June 5, 2017. Picture taken June 5, 2017. REUTERS/Edgar Su

Some hope to ditch the idea that robots need hands. German automation

company Festo and China's Beihang University have built a prototype

OctopusGripper, which has a pneumatic tentacle made of silicone that

gently wraps itself around an object, while air is pumped in or out of

suction cups to grasp it.

The ocean has inspired other robots, too.

A soft robot fish from China's Zhejiang University swims by ditching the

usual rigid motors and propellers for an artificial muscle which flexes.

It's lifelike enough, says creator Tiefeng Li, to fool other fish into

embracing it as one of their own, and is being tested to explore or

monitor water salinity.

And Bristol University in the UK is working on underwater robots that

generate electrical energy by foraging for biomatter to feed a chain of

microbial fuel-cell stomachs. Hemma Philamore says her team is talking

to companies and environmental organizations about using its soft robots

to decontaminate polluted waterways and monitor industrial

infrastructure.

This doesn't mean the end of hard-shelled robots.

Part of the problem, says Mark Freudenberg, executive technology

director at frog, a design company, is that soft materials break easily,

noting that most animatronic dolls like Teddy Ruxpin and Furby have

rigid motors and plastic casings beneath their fur exteriors.

To be sure, the nascent soft robot industry lacks an ecosystem of

software, hardware components and standards - and some companies have

already failed. Empire Robotics, one of the first soft robot gripper

companies, closed last year.

RightHand's Jentoft says the problem is that customers don't just want a

robot, but the whole package, including computer vision and machine

learning. "It's hard to be a standalone gripper company," he says.

And even if soft robots find a niche, chances are they still won't

replace all the jobs done by human or hard-shelled robots.

Wrench, whose Cambridge Consultants has built its own fruit picking

robot, says he expects to see soft robots working with humans to harvest

fruit like apples and pears which are harder to damage.

Once the robot has passed through, human pickers would follow to grab

fruit hidden behind leaves and in hard-to-reach spots.

"It's a constant race to the bottom, so there's a pressing business

need," Wrench said.

(Reporting by Jeremy Wagstaff; Editing by Ian Geoghegan)

[© 2017 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2017 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

|