|

Thirty years ago this week, Wall Street

slid into the abyss

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[October 19, 2017]

By Chuck Mikolajczak [October 19, 2017]

By Chuck Mikolajczak

NEW YORK (Reuters) - Thirty years ago,

before heading to work at the New York Stock Exchange, Peter Kenny left

his home in lower Manhattan and made a detour to the nearby Our Lady of

Victory church to pray to St. Jude, the Roman Catholic patron saint of

desperate and lost causes.

The reason was the stock market crash known as "Black Monday" on October

19, 1987.

"Blessed mother get me through this," he prayed.

Kenny, now senior market strategist at Global Markets Advisory Group in

New York, was a newly minted member of the New York Stock Exchange,

having joined the exchange in February that year. He was stunned by the

events that unfolded the previous day, the worst trading day in U.S.

history.

"I don’t think anyone was prepared for what actually transpired in the

overseas markets, which led to the bloodbath on Monday," said Kenny.

When it was over, the Dow Jones Industrial Average <.DJI> had lost 22.6

percent in one day, equivalent to a drop of about 5,200 points in the

index today. The benchmark U.S. S&P 500 index <.SPX> plunged 20.5

percent on Black Monday, equal to a drop of over 520 points today, and

the Nasdaq dropped 11.4 percent, comparable to a drop of about 750

points.

In 1987 U.S. stock prices had climbed steadily all year, as they have in

2017, with each of the three major U.S. indexes hitting record highs in

late August. But September turned into a difficult month, with each

index falling more than 2.0 percent, though not by enough to raise alarm

bells among investors.

But as the calendar flipped to October, the selling in U.S. equity

markets intensified. The Dow Jones Industrial Average <.DJI> and S&P 500

<.SPX> fell more than 9.0 percent in the week before Black Monday.

On the morning of Monday, October 19, 1987, Art Hogan, then a floor

broker at the Boston Stock Exchange, expected a possible rebound for

stock prices. Nothing had prepared him for what was to unfold.

"It was clear in that first hour... this was going to be as bad as we’ve

seen in our lifetimes," said Hogan, now chief market strategist at

Wunderlich Securities in New York.

Many describe the events of Black Monday as the first instance of

computer trading gone haywire, caused by the use of portfolio insurance,

a hedging strategy against market declines that involves selling short

in stock index futures.

The prior week's fall in U.S. stocks led to selling by investors in

Asian markets to limit losses. Those losses then signaled investors in

Europe to sell, which caused increased selling by the time U.S. markets

were to open on Black Monday.

"It was like nobody wanted to question the computer," said Ken Polcari,

director of the NYSE floor division at O’Neil Securities in New York,

who was a 26-year-old in his second year as a member of the NYSE.

[to top of second column] |

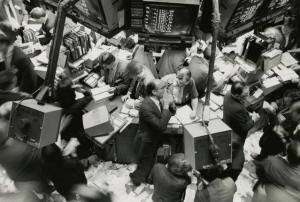

Traders on Black Monday. REUTERS/Courtesy NYSE

"Then what happens is it feeds on itself because as the prices got

worse the risk management software kept spitting out a new message -

You need to sell more," said Polcari.

Portfolio insurance, the short selling of stock index futures to

protect against a decline in value, caused computerized program

trading to issue sell orders as a safeguard against more losses.

Instead, losses intensified, causing even more sell orders in a

feedback loop.

With computer trading in its infancy, the floor of the NYSE was

filled with more members than today, with trades executed by hand on

paper. Thousands of traders scrambled to handle the tidal wave of

selling, with volumes so extreme prices were delayed by hours,

further complicating the process.

"The opening was 90 minutes (delayed), so you knew there was a lot

of influx of orders, the futures (contracts) were down, everything

was down, so we knew we were in for a rough ride," said Peter Costa,

president at Empire Executions Inc in New York, who has been working

on the trading floor since 1981.

The widespread selling and delay in reporting prices also hit the

stock options market, said Gordon Charlop, a managing director at

Rosenblatt Securities in New York who was trading options on the

American Exchange at the time of the crash.

"The options market slowed down to a crawl because nobody could

really figure out how to derive options prices from equities because

we weren’t sure what the equity prices were," said Charlop.

Of the 30 companies whose stocks are in the Dow today, slightly less

than half were in the index at the time. American Express <AXP.N>

lost 26.2 percent on Black Monday, Procter & Gamble <PG.N> plunged

27.8 percent, and Exxon Mobil <XOM.N> tumbled 23.4 percent.

"The price movements in the stocks were not like anything I had ever

seen prior to that day, or since that day, in fact," said Ted

Weisberg, floor trader with Seaport Securities in New York, who has

been a member of the exchange since 1969.

"It was in fact the scariest day, the most emotional day, except

when we came back to work after September 11, that I have ever spent

on the trading floor."

(Reporting by Chuck Mikolajczak; editing by Clive McKeef and Dan

Grebler)

[© 2017 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

Copyright 2017 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed. |