|

Missing hyphens will make it hard for

some people to vote in U.S. election

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[April 12, 2018]

By Tim Reid and Grant Smith [April 12, 2018]

By Tim Reid and Grant Smith

ATLANTA/NEW YORK (Reuters) - Fabiola Diaz,

18, sits in the food court of her Georgia high school and meticulously

fills out a voter registration form.

Driver’s license in one hand, she carefully writes her license number in

the box provided, her first name, last name, address, her eyes switching

from license to the paper form and back again to ensure every last

detail, down to hyphens and suffixes, is absolutely correct.

Diaz, and the voting rights activists holding a voter registration drive

at South Cobb High School in northern Atlanta, know why it is so

important not to make an error.

A law passed by the Republican-controlled Georgia state legislature last

year requires that all of the letters and numbers of the applicant's

name, date of birth, driver’s license number and last four digits of

their Social Security number exactly match the same letters and numbers

in the motor vehicle department or Social Security databases.

The tiniest discrepancy on a registration form places them on a

“pending” voter list that could deter people from voting. A Reuters

analysis of Georgia's pending voter list, obtained through a public

records request, found that black voters landed on the list at a far

higher rate than white voters even though a majority of Georgia's voters

are white.

Both voting rights activists and Georgia's state government say the

reason for this is that blacks more frequently fill out paper forms than

whites, who are more likely to do them online. Paper forms are more

prone to human error, both sides agree. But they disagree on whether the

errors are made by those filling out the forms or officials processing

the forms.

Republicans say the aim of the "exact match" law is to prevent voter

fraud. Voting rights groups, however, object to an inadvertent error

creating an obstacle to a person’s fundamental right to vote.

Democrats and voting rights groups say the exact match law could make

the difference in a tight congressional election, like the one in

Georgia's 6th congressional district in November, as blacks tend to vote

for the Democratic Party. If Democrats can gain 24 seats they will be

able to win control of the U.S. House of Representatives and block

President Donald Trump's legislative agenda.

A few thousand votes could decide the race in the 6th district. In a

special election there last year, Republican Karen Handel defeated

Democrat Jon Ossoff by just over 9,000 votes, out of about 260,000 cast.

Trump won the northern Atlanta district by 1 percent of the vote in

2016.

DISPARITY

The Democratic Party has said that changes to voting laws in

Republican-controlled states are part of a concerted effort to reduce

turnout among particular groups of voters on election day. Republicans

deny that the voting laws are discriminatory and say they are intended

to reduce fraudulent votes.

In Georgia, exact match was state policy for several years. The state

was sued over the policy and settled the case in February 2017. Later in

the year the Republican-controlled statehouse made it law, with some

changes. That new law will be in effect for the first time in statewide

elections this November.

Under the new law, voters placed on the list do have 26 months to

rectify any error, and if they present a valid ID card at a polling

place, they can vote. But voting activists say many people may not

realize they are on the pending list in the first place.

When a voter on a pending list checks their personal voter page on the

Georgia Secretary of State’s website, it tells them to check their

status with county officials. Nowhere does it inform the voter that they

have been placed in pending status.

Voting groups say some minority voters don’t have access to the state’s

website as they do not own computers. Additionally, based on past

experiences with exact match, they say temporary poll workers sometimes

do not know how to fix errors or what pending status actually means.

[to top of second column]

|

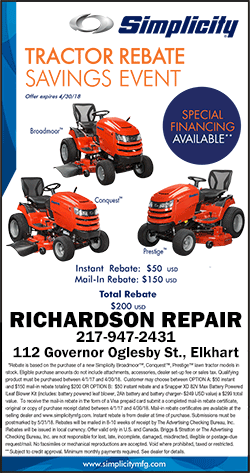

South Cobb High School senior Fabiola Diaz, 18, carefully

double-checks the details on her driver's license as she registers

to vote during a registration drive by voting rights group New

Project Georgia in Austell, Georgia, U.S. February 6, 2018. Picture

taken February 6, 2018. REUTERS/Chris Aluka Berry

Ohio and Florida are the only other states to implement exact match

provisions since 2008, according to the non-partisan Brennan Center

for Justice at NYU School of Law, which advocates for voting rights

and fair elections.

More than 82 percent of the roughly 56,000 voter registrants given

“pending” voter status in Georgia between August 2013 and February

2018 were there because they had fallen foul of the exact match

policy, according to state data reviewed by Reuters. (Graphic

https://tmsnrt.rs/2H9ZFZ7)

In a state where roughly 31 percent of residents are African

American, nearly 72 percent of those on that list were African

American. Just under 10 percent of the people on the list were white

although, according to 2016 U.S. Census data, 54 percent of

Georgia's population are white non-Hispanics.

Voting rights groups say based on their experience of previous

elections, the practice of exact match sows confusion, suppressing

turnout, and that overstretched county workers are more likely to

add a voter to a pending list to save time and meet deadlines.

Brian Kemp, Georgia's Republican secretary of state, manages the

state's elections. He argues the state's exact-match law is fair.

Candice Broce, a spokesperson for Kemp, said more blacks end up on

the pending voter list than whites because black voters used paper

registrations more often than white voters.

THE PROBLEM WITH PAPER

Georgia contends that more than twice as many black residents

registered to vote by paper than did white residents, and that

substantially all of the pending voters came from paper

registrations.

Broce blamed voter registration groups such as the New Georgia

Project, which held the registration drive at Diaz's high school,

for registering voters predominately with paper forms, and then

turning in "incomplete, illegible, or fraudulent forms," which skews

the data.

Broce added there was no significant racial disparity in voters

landing on the pending list when they registered online. She said

the issue "is limited to paper applications."

Nse Ufot, executive director of New Georgia Project, called Broce's

comments "ridiculous" and said the problem was most likely caused by

human error during the state's transcription of the data on the

paper forms to a computer. Errors occur because the counties, who

record registrations, are short-staffed, workers are improperly

trained, and often in a hurry to make election deadlines, she said.

Voting rights could become a flashpoint in this November’s race for

governor in Georgia.

Kemp, the secretary of state, is running for office, as is Stacey

Abrams, the former Democratic House minority leader in Georgia’s

state assembly and the founder of the New Georgia Project. The two

have clashed in the past, with Kemp accusing the group of voter

fraud, and Abrams accusing Kemp of voter suppression.

(Reporting by Tim Reid and Grant Smith; Editing by Damon Darlin and

Ross Colvin)

[© 2018 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

Copyright 2018 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |