|

How the families of 10 massacred Rohingya

fled Myanmar

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[April 12, 2018]

By Andrew R.C. Marshall [April 12, 2018]

By Andrew R.C. Marshall

KUTUPALONG REFUGEE CAMP, Bangladesh

(Reuters) - Rehana Khatun dreamed her husband came home. He appeared

without warning in their village in western Myanmar, outside their

handsome wooden house shaded by mango trees. "He didn't say anything,"

she said. "He was only there for a few seconds, and then he was gone."

Then Rehana Khatun woke up.

She woke up in a shack of ragged tarpaulin on a dusty hillside in

Bangladesh. Her husband, Nur Mohammed, is never coming home. He was one

of 10 Rohingya Muslim men massacred last September by Myanmar soldiers

and Rakhine Buddhists at the coastal village of Inn Din.

(FOR AN INTERACTIVE VERSION OF THIS STORY - click

https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/myanmar-massacre-survivors/)

Rehana Khatun's handsome wooden house is gone, too. So is everything in

it. The Rohingya homes in Inn Din were burned to the ground, and what

was once a close-knit community, with generations of history in Myanmar,

is now scattered across the world's largest refugee camp in Bangladesh.

A Reuters investigation in February revealed what happened to the 10

Rohingya men. On September 1, soldiers snatched them from a large group

of Rohingya villagers detained by a beach near Inn Din. The next

morning, according to eyewitnesses, the men were shot by the soldiers or

hacked to death by their Rakhine Buddhist neighbors. Their bodies were

dumped in a shallow grave.

The relatives the 10 men left behind that afternoon wouldn't learn of

the killings for many months - in some cases, not until Reuters

reporters tracked them down in the refugee camps and told them what had

happened. The survivors waited by the beach with rising anxiety and

dread as the sun set and the men didn't return.

This is their story. Three of them fled Inn Din while heavily pregnant.

All trekked north in monsoon rain through forests and fields. Drenched

and terrified, they dodged military patrols and saw villages abandoned

or burning. Some saw dead bodies. They walked for days with little food

or water.

They were not alone. Inn Din's families joined nearly 700,000 Rohingya

escaping a crackdown by the Myanmar military, launched after attacks by

Rohingya militants on August 25. The United Nations called it "a

textbook example of ethnic cleansing," which Myanmar has denied.

On Tuesday, the military said it had sentenced seven soldiers to long

prison terms for their role in the Inn Din massacre. Myanmar government

spokesman Zaw Htay told Reuters the move was a "very positive step" that

showed the military "won't give impunity for those who have violated the

rules of engagement." Myanmar, he said, doesn't allow systematic human

rights abuses.

Reuters was able to corroborate many but not all details of the personal

accounts in this story.

The Rohingya streamed north until they reached the banks of the Naf

River. On its far shore lay Bangladesh, and safety. Many Inn Din women

gave boatmen their jewelry to pay for the crossing; others begged and

fought their way on board. They made the perilous crossing at night,

vomiting with sickness and fear.

Now in Bangladesh, they struggle to piece together their lives without

husbands, fathers, brothers and sons. Seven months have passed since the

massacre, but the grief of Inn Din's survivors remains raw. One mother

told Reuters her story, then fainted.

Like Rehana Khatun, they all say they dream constantly about the dead.

Some dreams are bittersweet - a husband coming home, a son praying in

the mosque - and some are nightmares. One woman says she sees her

husband clutching a stomach wound, blood oozing through his fingers.

Daytime brings little relief. They all remember, with tormenting

clarity, the day the soldiers took their men away.

"ALLAH SAVED ME"

Abdul Amin still wonders why he was spared.

Soldiers had arrived at Inn Din on August 27 and started torching the

houses of Rohingya residents with the help of police and Rakhine

villagers. Amin, 19, said he and his family sought refuge in a nearby

forest with more than a hundred other Rohingya.

Four days later, as Inn Din burned and the sound of gunfire crackled

through the trees, they made a dash for the beach, where hundreds of

villagers gathered in the hope of escaping the military crackdown. Then

the soldiers appeared, said Amin, and ordered them to squat with their

heads down.

Amin crouched next to his mother, Nurasha, who threw her scarf over his

head. The soldiers ignored Amin, perhaps mistaking him for a woman, but

dragged away his brother Shaker Ahmed. "I don't know why they chose him

and not me," Amin said. "Allah saved me."

The soldiers, according to Amin and other witnesses, said they were

taking the men away for a "meeting." Their distraught families waited by

the beach in vain. As night fell, they returned to the forest where, in

the coming days, they made the decision that haunts many of them still:

to save themselves and their families by fleeing to Bangladesh - and

leaving the captive men behind.

Abdu Shakur waited five days for the soldiers to release his son Rashid

Ahmed, 18. By then, most Rohingya had set out for Bangladesh and the

forest felt lonely and exposed. Abdu Shakur said he wanted to leave,

too, but his wife, Subiya Hatu, refused.

"I won't go without my son," she said.

"You must come with me," he said. "If we stay here, they'll kill us

all." They had three younger children to bring to safety, he told her.

Rashid was their oldest, a bright boy who loved to study; he would

surely be released soon and follow them. He didn't. Rashid was one of

the 10 killed in the Inn Din massacre.

"We did the right thing," says Abdu Shakur today, in a shack in the

Kutupalong camp. "I feel terrible, but we had to leave that place." As

he spoke, his wife sat behind him and sobbed into her headscarf.

"DAY OF JUDGMENT"

By now, the northward exodus was gathering pace. The Rohingya walked in

large groups, sometimes thousands strong, stretching in ragged columns

along the wild Rakhine coastline. At night, the men stood guard while

women and children rested beneath scraps of tarpaulin. Rain often made

sleep impossible.

Amid this desperate throng was Shaker Ahmed's wife, Rahama Khatun, who

was seven months pregnant, and their eight children, aged one to 18.

Like many Rohingya, they had escaped Inn Din with little more than the

clothes they wore. "We brought nothing from the house, not even a single

plate," she said.

[to top of second column]

|

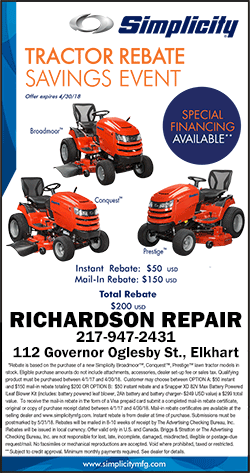

From left: Hasina Khatun, Marjan, Nurjan, Abdu Shakur, Shuna Khatu,

Nurjan, Rahama Khatun, Amina Khatun, Settara, Hasina Khatun;

relatives of ten Rohingya men killed by Myanmar security forces and

Buddhist villagers on September 2, 2017, pose for a group photo in

Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, March 23, 2018. REUTERS/Mohammad Ponir

Hossain

They survived the journey by drinking from streams and scrounging

food from other refugees. Rahama said she heaved herself along

slippery paths as quickly as she could. She was scared about the

health of her unborn child, but terrified of getting left behind.

Rahama's legs swelled up so much that she couldn't walk. "My

children carried me on their shoulders. They said, 'We've lost our

father. We don't want to lose you.'" Then they reached the beach at

Na Khaung To, and a new ordeal began.

Na Khaung To sits on the Myanmar side of the Naf River. Bangladesh

is about 6 km (4 miles) away. For Rohingya from Inn Din and other

coastal villages, Na Khaung To was the main crossing point.

It was also a bottleneck. There were many Bangladeshi fishing boats

to smuggle Rohingya across the river, but getting on board depended

on the money or valuables the refugees could muster and the mercy of

the boatmen. Some were stranded at Na Khaung To for weeks.

The beach was teeming with sick, hungry and exhausted people,

recalled Nurjan, whose son Nur Mohammed was one of the 10 men killed

at Inn Din. "Everyone was desperate," Nurjan said. "All you could

see was heads in every direction. It was like the Day of Judgment."

CROSSING THE NAF

Bangladesh was perhaps a two-hour ride across calm estuarine waters.

But the boatmen wanted to avoid any Bangladesh navy or border guard

vessels that might be patrolling the river. So they set off at

night, taking a more circuitous route through open ocean. Most boats

were overloaded. Some sank in the choppy water, drowning dozens of

people.

The boatmen charged about 8,000 taka (about $100) per person. Some

women paid with their earrings and nose-rings. Others, like Abdu

Shakur, promised to reimburse the boatman upon reaching Bangladesh

with money borrowed from relatives there.

He and his wife, Subiya Hatu, who had argued over leaving their

oldest son behind at Inn Din, set sail for Bangladesh. Another boat

of refugees sailed along nearby. Both vessels were heaving with

passengers, many of them children.

In deeper water, Abdu Shakur watched with horror as the other boat

began to capsize, spilling its passengers into the waves. "We could

hear people crying for help," he said. "It was impossible to rescue

them. Our boat would have sunk, too."

Abdu Shakur and his family made it safely to Bangladesh. So did the

other families bereaved by the Inn Din massacre. During the

crossing, some realized they would never see their men again, or

Myanmar.

Shuna Khatu wept on the boat. She felt she already knew what the

military had done to her husband, Habizu. She was pregnant with

their third child. "They killed my husband. They burned my house.

They destroyed our village," she said. "I knew I'd never go back."

THE ONLY PHOTO

Two months later, in a city-sized refugee camp in Bangladesh, Shuna

Khatu gave birth to a boy. She called him Mohammed Sadek.

Rahama Khatun, who fled Myanmar on the shoulders of her older

children while seven months pregnant, also had a son. His name is

Sadikur Rahman.

The two women were close neighbors in Inn Din. They now live about a

mile apart in Kutupalong-Balukhali, a so-called "mega-camp" of about

600,000 souls. Both survive on twice-a-month rations of rice,

lentils and cooking oil. They live in flimsy, mud-floored shacks of

bamboo and plastic that the coming monsoon could blow or wash away.

It was here, as the families struggled to rebuild their lives, that

they learned their men were dead. Some heard the news from Reuters

reporters who had tracked them down. Others saw the Reuters

investigation of the Inn Din massacre or the photos that accompanied

it.

Two of those photos showed the men kneeling with their hands behind

their backs or necks. A third showed the men's bodies in a mass

grave. The photos were obtained by Reuters reporters Wa Lone and

Kyaw Soe Oo, who were arrested in December while investigating the

Inn Din massacre. The two face charges, and potentially 14-year jail

sentences, under Myanmar's Official Secrets Act.

Rahama Khatun cropped her husband's image from one of the photos and

laminated it. This image of him kneeling before his captors is the

only one she has. Every other family photo was burned along with

their home at Inn Din.

(Reporting by Andrew R.C. Marshall. Edited by Peter Hirschberg.)

[© 2018 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

Copyright 2018 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|