|

Tent city for migrant children puts Texas

border town in limelight

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[June 21, 2018]

By Jon Herskovitz [June 21, 2018]

By Jon Herskovitz

TORNILLO, Texas (Reuters) - A small Texas

farming community near El Paso with no traffic lights, a cotton gin and

two dollar stores has found itself playing the uncomfortable host to a

U.S. government tent city for children suspected of illegal border

crossings.

In a quiet corner of Texas with vast desert spaces, dusty roads and

cotton fields, Tornillo was thrust into the limelight when the first

tents went up last week.

The tent city has come under scrutiny amid outcry at home and abroad

over the Trump administration's policy of separating parents and

children after families cross the border from Mexico illegally.

President Donald Trump, who had staunchly defended the policy and sought

to blame Democrats even though his administration implemented the strict

adherence to immigration law, changed course on Wednesday, signing an

executive order to end the separation.

The order requires immigrant families be detained together when they are

caught entering the country illegally, although it was not immediately

clear for how long.

A local congressman has said that only "unaccompanied minors" were

housed in the Tornillo facility but it was not immediately clear whether

they were apprehended without adults or separated from parents after

apprehension.

Will Hurd, the Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives

whose district includes Tornillo, said in comments prepared by his

office that "these types of tent cities would not be going up" without

the new policy.

Hurd, who said "we should not use children as a deterrent, plain and

simple" in a social media post, last week visited the facility, which is

near a border crossing point. In the statement released by his office,

he said it appeared to be safe and well run.

Each tent can hold 20 children and two adults. Those in the camp are

currently 16 and 17-year-old boys, Hurd said.

Children who traveled with their parents and were then separated when

the adults were apprehended are at the center of the current storm.

In Tornillo, a town of about 1,600 people some 30 miles (50 km)

southeast of El Paso with a large Latino population, it was difficult to

find anyone who would voice support for the policy.

"I wish that Tornillo as a town was not going to be remembered

throughout the nation as the place where there are tents for children,"

said Rosy Vega-Barrio, superintendent of the Tornillo Independent School

District. Tornillo does not have a government or a police department.

The family separations began after Attorney General Jeff Sessions

announced in April the government would prosecute all immigrants

apprehended while crossing the U.S.-Mexico border illegally.

While parents are in custody pending trial, their children are moved

into government-managed facilities, a separation that looked set to end

with Trump's new order. An administration official said the order would

require families to be detained together if they were caught crossing

the border illegally.

Vega-Barrio said a county official described the detention camp to her

as a "mini-prison" and informed her that the children there would not

attend Tornillo's schools.

[to top of second column]

|

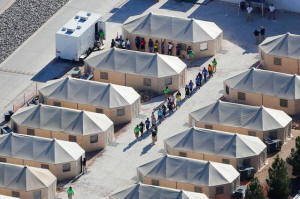

Immigrant children now housed in a tent encampment are shown walking

in single file at the facility near the Mexican border in Tornillo,

Texas, June 19, 2018. REUTERS/Mike Blake

FIGHTING THE HEAT

For many in Tornillo, the facility is a different world, set off a

few miles from the town and staffed by people who live in other

places. Aerial photographs from Reuters show the tent city almost

doubled in size from Monday to Tuesday to house nearly 20 large

tents, each equipped with air conditioning to fight off summer

temperatures that hover above 100 Fahrenheit (38 Celsius) daily.

Children accompanied by guards can be seen walking single file

through the facility, where portable toilets and showers have been

set up. Last week, children could be seen kicking around a soccer

ball on land baked dry by the unrelenting sun. An aerial view showed

that an artificial turf playing field was being constructed.

The tents have bunk beds, according to the Administration for

Children & Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services (HHS), which has a hand in the running the facility.

It has not let in the media to see it.

The HHS did not respond to a request for comment about the camp,

which Hurd said could hold as many as 400 children.

U.S. immigration officials have experience in setting up a tent city

at the facility, which was used in 2016 when there was a surge in

migrants from Central America trying to enter the United States,

U.S. Customs and Border Protection said.

Beto OíRourke, a U.S. Democratic representative for El Paso, said

that U.S. government officials blocked him from seeing the children

housed at the camp. He was at the facility on Sunday in a protest

against the separation policy.

"They let you come in the front door as a member of Congress but

they donít let you see the kids," he said.

For a quarter century, Josie Pogorzelski, 60, has lived in a house a

few yards away from the immigration facility, which has kept to its

side of the fence with little bother to her.

"I didn't know what was happening next door until I saw it on TV

this morning," she said on Tuesday.

(Reporting by Jon Herskovitz; Editing by Frank McGurty, Frances

Kerry and Lisa Shumaker)

[© 2018 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

Copyright 2018 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |