|

Their error was only discovered by chance late last year when

more recent academics removed the lid to the coffin and

discovered the tattered remains of a mummy.

The discovery offers scientists an almost unique opportunity to

test the cadaver.

"We can start asking some intimate questions that those bones

will hold around pathology, about diet, about diseases, about

the lifestyle of that person - how they lived and died," said

Jamie Fraser, senior curator at the Nicholson Museum at the

University of Sydney.

Whole mummies are typically left intact, limiting their

scientific benefits.

Adding to the potential rewards is the possibility that the

remains are those of a distinguished woman of an age where

little is known, Fraser said.

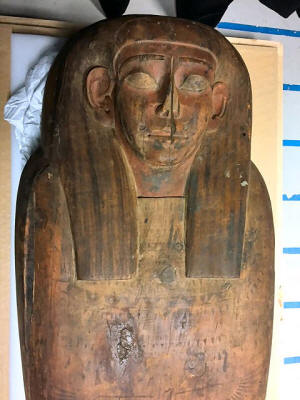

Hieroglyphs show the original occupant of the coffin was a

female called Mer-Neith-it-es, who academics believe was a high

priestess in 600 BC, the last time Egypt was ruled by native

Egyptians.

"We know from the hieroglyphs that Mer-Neith-it-es worked in the

Temple of Sekhmet, the lion-headed goddess," Fraser said.

"There are some clues in hieroglyphs and the way the

mummification has been done and the style of the coffin that

tell us about how this Temple of Sekhmet may have worked."

(Reporting by Colin Packham; Editing by Paul Tait)

[© 2018 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2018 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|

|