|

China's military-run space station in

Argentina is a 'black box'

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[January 31, 2019]

By Cassandra Garrison [January 31, 2019]

By Cassandra Garrison

LAS LAJAS, Argentina - When China built a

military-run space station in Argentina's Patagonian region it promised

to include a visitors' center to explain the purpose of its powerful

16-story antenna.

The center is now built - behind the 8-foot barbed wire fence that

surrounds the entire space station compound. Visits are by appointment

only.

Shrouded in secrecy, the compound has stirred unease among local

residents, fueled conspiracy theories and sparked concerns in the Trump

administration about its true purpose, according to interviews with

dozens of residents, current and former Argentine government officials,

U.S. officials, satellite and astronomy specialists and legal experts.

The station's stated aim is peaceful space observation and exploration

and, according to Chinese media, it played a key role in China’s landing

of a spacecraft on the dark side of the moon in January.

But the remote 200-hectare compound operates with littleoversight by the

Argentine authorities, according to hundreds of pages of Argentine

government documents obtained by Reuters and reviewed by international

law experts. (For an interactive version of this story: https://tmsnrt.rs/2TlXEMj)

President Mauricio Macri's former foreign minister, Susana Malcorra,

said in an interview that Argentina has no physical oversight of the

station's operations. In 2016, she revised the China space station deal

to include a stipulation it be for civilian use only.

The agreement obliges China to inform Argentina of its activities at the

station but provides no enforcement mechanism for authorities to ensure

it is not being used for military purposes, the international law

experts said.

"It really doesn't matter what it says in the contract or in the

agreement," said Juan Uriburu, an Argentine lawyer who worked on two

major Argentina-China joint ventures. "How do you make sure they play by

the rules?"

"I would say that, given that one of the actors involved in the

agreements reports directly to the Chinese military, it is at least

intriguing to see that the Argentine government did not deal with this

issue with greater specificity," he said.

China's space program is run by its military, the People's Liberation

Army. The Patagonian station is managed by the China Satellite Launch

and Tracking Control General (CLTC), which reports to the PLA's

Strategic Support Force.

Beijing insists its space program is for peaceful purposes and its

foreign ministry in a statement stressed the Argentine station is for

civilian use only. It said the station was open to the public and media.

"The suspicions of some individuals have ulterior motives," the ministry

said.

Asked how it ensures the station is not used for military purposes,

Argentina's space agency CONAE said the agreement between the two

countries stated their commitment to "peaceful use" of the project.

It said radio emissions from the station were also monitored, but radio

astronomy experts said the Chinese could easily hide illicit data in

these transmissions or add encrypted channels to the frequencies agreed

upon with Argentina.

CONAE also said it had no staff permanently based at the station, but

they made "periodic" trips there.

SPYING CONCERNS

The United States has long been worried about what it sees as China's

strategy to "militarize" space, according to one U.S. official, who

added there was reason to be skeptical of Beijing's insistence that the

Argentine base was strictly for exploration.

Other U.S. officials who spoke to Reuters expressed similar concerns.

“The Patagonia ground station, agreed to in secret by a corrupt and

financially vulnerable government a decade ago, is another example of

opaque and predatory Chinese dealings that undermine the sovereignty of

host nations,” said Garrett Marquis, spokesman for the White House

National Security Council.

Some radio astronomy experts said U.S. concerns were overblown and the

station was probably as advertised - a scientific venture with Argentina

- even if its 35-meter diameter dish could eavesdrop on foreign

satellites.

Tony Beasley, director of the U.S. National Radio Astronomy Observatory,

said the station could, in theory, "listen" to other governments'

satellites, potentially picking up sensitive data. But that kind of

listening could be done with far less sophisticated equipment.

“Anyone can do that. I can do that with a dish in my back yard,

basically," Beasley said. "I don't know that there's anything

particularly sinister or troubling about any part of China's space radio

network in Argentina."

Argentine officials have defended the Chinese station, saying the

agreement with China is similar to one signed with the European Space

Agency, which built a station in a neighboring province. Both have

50-year, tax-free leases. Argentine scientists in theory have access to

10 percent of the antenna time at both stations.

The law experts who reviewed the documents said there is one notable

difference: ESA is a civilian agency.

"All of the ESA governments play by democratic rules," Uriburu said.

"The party is not the state. But that’s not the case in China. The party

is the state."

In the United States, NASA, like the ESA, is a civilian agency, while

the U.S. military has it own space command for military or national

security missions. In some instances, NASA and the military have

collaborated, said Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

"The line does blur sometimes," he said. "But that's very much the

exception."

[to top of second column]

|

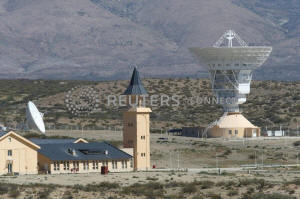

The installations of a Chinese space station are seen in Las Lajas,

Argentina, January 22, 2019. Picture taken January 22, 2019.

REUTERS/Agustin Marcarian

BLACK BOX

In Las Lajas, a town of 7,000 people located about 40 minutes drive

from the station, the antenna is a source of bewilderment and

suspicion.

"These people don't allow you access, they don't let you see," said

shop owner Alfredo Garrido, 51. "My opinion is that it is not a

scientific research base, but rather a Chinese military base."

Among the wilder conspiracy theories reporters heard during a visit

to the town: That the base was being used to build a nuclear bomb.

The drive from Las Lajas to the space station is barren and dusty.

There are no signs indicating the station's existence. The sprawling

antenna is suddenly visible after a curve in the gravel road off the

main thoroughfare. The massive dish is the only sign of human life

for miles around.

The station became operational in April. Thirty Chinese employees

work and live on site, which employs no locals, according to the Las

Lajas mayor, Maria Espinosa, adding that the station has been good

for the local economy.

Espinosa said she rented her house to Chinese space station workers

before they moved to the base and had visited the site herself at

least eight times.

Others in Las Lajas said they rarely see anyone from the station in

town, except when the staff make a trip to its Chinese supermarket.

Reuters requested access to the station through CONAE, the local

provincial government and China's embassy. CONAE said it was not

able to approve a visit by Reuters in the short term but it was

planning a media day.

It added that students from nearby towns have already visited the

compound.

NO OVERSIGHT

When Argentina's Congress debated the space station in 2015, during

the presidency of Cristina Fernandez, opposition lawmakers

questioned why there was no stipulation that it only be for civilian

use. Nonetheless, Congress approved the deal.

When Macri took office in 2015 he was worried the space station

agreement did not explicitly say it should be for civilian use only,

said Malcorra, his then foreign minister, who flew to Beijing in

2016 to rework it.

Malcorra said she was constrained in her ability to revise it

because it had already been signed by Fernandez. The Chinese,

however, agreed to include the stipulation that it be for civilian

use. She insisted on a press conference with her Chinese counterpart

in Beijing to publicize this.

"This was something I requested to make sure there was no doubt or

no hidden agenda from any side here, and that our people knew that

we had done this," she said from her home in Spain.

But it still fell short on one key point - oversight.

"There was no way we could do that after the level of recognition

that this agreement had from our side. This was recognized, accepted

and approved by Congress," Malcorra said.

"I would have written the agreement in a different way," she added.

"I would have clauses that articulate the access to oversight."

Malcorra said she was confident that Argentina could approach China

for "reassurances" if there was ever any doubt about activities at

the station. When asked how Argentina would know about those

activities, she said, "There will be some people who will tell us,

don't worry."

LOGGING VISITORS

The opaqueness of the station's operations and the reluctance of

Argentine officials to talk about it makes it hard to determine who

exactly has visited the compound.

A provincial government official provided Reuters a list of local

journalists who had toured the facility. A number appeared to have

visited on a single day in February 2017, 14 months before it became

operational, a review of their stories and social media postings

showed.

Aside from Espinosa, the mayor of Las Lajas, no one else interviewed

by Reuters in town had toured the station. Resident Matias Uran, 24,

however, said his sister was among a group of students who visited

last year. They saw a dining room and a games room, he said.

Alberto Hugo Amarilla, 60, who runs a small hotel in Las Lajas,

recalled a dinner he attended shortly after construction began at

the site.

There, he said, a Chinese official in town to visit the site greeted

him enthusiastically. His fellow dinner guests told him the official

had learned that Amarilla was a retired army officer.

The official, they said, was a Chinese general.

(Reporting by Cassandra Garrison; Additional reporting by Dave

Sherwood in SANTIAGO, Matt Spetalnick, Mark Hosenball and Phil

Stewart in WASHINGTON, Joey Roulette in ORLANDO, Michael Martina in

BEIJING; Editing by Ross Colvin, Julie Marquis and Paul Thomasch)

[© 2019 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

Copyright 2019 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|