Wall Street banks bailing on troubled U.S. farm sector

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[July 11, 2019] By

P.J. Huffstutter and Jason Lange [July 11, 2019] By

P.J. Huffstutter and Jason Lange

CHICAGO/

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - In the wake

of the U.S. housing meltdown of the late 2000s, JPMorgan Chase & Co

hunted for new ways to expand its loan business beyond the troubled

mortgage sector.

The nation's largest bank found enticing new opportunities in the rural

Midwest - lending to U.S. farmers who had plenty of income and

collateral as prices for grain and farmland surged.

JPMorgan grew its farm-loan portfolio by 76 percent, to $1.1 billion,

between 2008 and 2015, according to year-end figures, as other Wall

Street players piled into the sector. Total U.S. farm debt is on track

to rise to $427 billion this year, up from an inflation-adjusted $317

billion a decade earlier and approaching levels seen in the 1980s farm

crisis, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

But now - after years of falling farm income and an intensifying

U.S.-China trade war - JPMorgan and other Wall Street banks are heading

for the exits, according to a Reuters analysis of the farm-loan holdings

they reported to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

The agricultural loan portfolios of the nation's top 30 banks fell by

$3.9 billion, to $18.3 billion, between their peak in December 2015 and

March 2019, the analysis showed. That's a 17.5% decline. (GRAPHIC:

https://tmsnrt.rs/2X4BNz9 )

Reuters identified the largest banks by their quarterly filings of loan

performance metrics with the FDIC and grouped together banks owned by

the same holding company. The banks were ranked by total assets in the

first quarter of this year.

The retreat from agricultural lending by the nation's biggest banks,

which has not been previously reported, comes as shrinking cash flow is

pushing some farmers to retire early and others to declare bankruptcy,

according to farm economists, legal experts, and a review of hundreds of

lawsuits filed in federal and state courts.

Sales of many U.S. farm products - including soybeans, the nation's most

valuable agricultural export - have fallen sharply since China and

Mexico last year imposed tariffs in retaliation for U.S. duties on their

goods. The trade-war losses further strained an agricultural economy

already reeling from years over global oversupply and low commodity

prices.

Chapter 12 federal court filings, a type of bankruptcy protection

largely for small farmers, increased from 361 filings in 2014 to 498 in

2018, according to federal court records.

"My phone is ringing constantly. It's all farmers," said Minneapolis-St.

Paul area bankruptcy attorney Barbara May. "Their banks are calling in

the loans and cutting them off."

Surveys show demand for farm credit continues to grow, particularly

among Midwest grain and soybean producers, said regulators at the

Federal Reserve Banks of Chicago, St. Louis, Minneapolis and Kansas

City. U.S. farmers rely on loans to buy or refinance land and to pay for

operational expenses such as equipment, seeds and pesticides.

Fewer loan options can threaten a farm's survival, particularly in an

era when farm incomes have been cut nearly in half since 2013.

Gordon Giese, a 66-year-old dairy and corn farmer in Mayville,

Wisconsin, last year was forced to sell most of his cows, his farmhouse

and about one-third of his land to clear his farm's debt. Now, his wife

works 16-hour shifts at a local nursing home to help pay bills.

Giese and two of his sons tried and failed to get a line of credit for

the farm.

"If you have any signs of trouble, the banks don’t want to work with

you," said Giese, whose experience echoes dozens of other farmers

interviewed by Reuters. "I don’t want to get out of farming, but we

might be forced to."

Michelle Bowman, a governor at the U.S. Federal Reserve, told an

agricultural banking conference in March that the sharp decline in farm

incomes was a "troubling echo" of the 1980s farm crisis, when falling

crop and land prices, amid rising debt, lead to mass loan defaults and

foreclosures.

JPMorgan Chase's FDIC-insured units pared $245 million, or 22%, of their

farm-loan holdings between the end of 2015 and March 31 of this year.

JPMorgan Chase did not dispute Reuters' findings but said it has not

"strategically reduced" its exposure to the farm sector. The bank said

in a statement that it has a broader definition of agricultural lending

than the FDIC. In addition to farmers, the bank includes processors,

food companies and other related business.

(For a graphic on 'Rising loan delinquencies' click https://tmsnrt.rs/2Fx1I7z)

[to top of second column] |

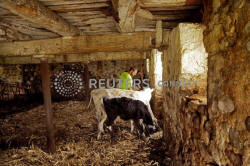

Paul Giese, feeds some newly acquired dairy calves at the family

farm, God Green Acres in Mayville, Wisconsin, U.S., June 24, 2019.

Picture taken June 24, 2019. REUTERS/Darren Hauck

FEDERAL BACKING FOR SMALLER BANKS

The decline in farm lending by the big banks has come despite ongoing growth in

the farm-loan portfolios of the wider banking industry and in the

government-sponsored Farm Credit System. But overall growth has slowed

considerably, which banking experts called a sign that all lenders are growing

more cautious about the sector.

The four-quarter growth rate for farm loans at all FDIC-insured banks, which

supply about half of all farm credit, slowed from 6.4% in December 2015 to 3.9%

in March 2019. Growth in holdings of comparable farm loans in the Farm Credit

System has also slowed.

Many smaller, rural banks are more dependent on their farm lending portfolios

than the national banks because they have few other options for lending in their

communities. As farming towns have seen populations shrink, so have the number

of businesses, said Curt Everson, president of the South Dakota Bankers

Association.

"All you have are farmers and companies that work with, sell to or buy from

farmers," Everson said.

As the perils have grown, some smaller banks have turned to the federal

government for protection, tapping a U.S. Department of Agriculture program that

guarantees up to 95% of a loan as a way to help rural and community banks lend

to higher-risk farmers.

Big Wall Street banks have steadily trimmed their farm portfolios since 2015

after boosting their lending in the sector in the wake of the financial crisis.

Capital One Financial Corp’s farm-loan holdings at FDIC-insured units fell 33%

between the end of 2015 and March 2019. U.S. Bancorp’s shrunk by 25%.

Capital One Financial Corp did not respond to requests for comment. U.S. Bancorp

declined to comment.

The agricultural loan holdings at BB&T Corp have fallen 29% since peaking in the

summer of 2016 at $1.2 billion. PNC Financial Services Group Inc - which ran

full-page ads in farm trade magazines promoting “access to credit” during the

run-up – has cut its farm loans by 12% since 2015.

BB&T said in a statement that the decline in its agricultural lending portfolio

"is largely due to aggressive terms and pricing" offered by competitors and its

"conservative and disciplined" approach to risk.

PNC said its farm-loan growth is being held back by customers who are wary of

taking new debt, along with increased competition from the Farm Credit System.

LOAN DEMAND STILL RISING

Lenders are avoiding mounting risks in a category that is not core to their

business, said Curt Hudnutt, head of rural banking for Rabobank North America, a

major farm lender and subsidiary of Dutch financial giant Rabobank Group.

In March of this year, FDIC-insured banks reported that 1.53% of their farm

loans were at least 90 days past due or had stopped accruing interest because

the lender has doubts it will be repaid. This so-called noncurrent rate had

doubled from 0.74% at the end of 2015. (GRAPHIC: https://tmsnrt.rs/2X3hbac )

The noncurrent rates were far higher on the farm loans of some big Wall Street

banks. Bank of America Corp's noncurrent rate for farm loans at its FDIC-insured

units has surged to 4.1% from 0.6% at the end of 2015. Meanwhile, the bank has

cut the value of its farm-loan portfolio by about a quarter over the same

period, from $3.32 billion to $2.47 billion, according to the most recent FDIC

data.

Bank of America declined to comment on the data or its lending decisions.

For PNC Financial Services, the noncurrent rate was nearly 6% as of the end of

March. It cut its farm-loan portfolio to $278.4 million, down from $317.3

million at the end of 2015.

David Oppedahl, senior business economist for the Federal Reserve Bank of

Chicago, said the banking community is increasingly aware of how many farmers

are struggling.

“They don’t want to be the ones caught holding bad loans,” he said.

(Reporting by P.J. Huffstutter in Chicago and Jason Lange in Washington;

Additional reporting by Elizabeth Dilts and Ayenat Mersie in New York, and Pete

Schroeder in Washington; Editing by Caroline Stauffer and Brian Thevenot)

[© 2019 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2019 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |