U.S. minority students concentrated in high-poverty schools: study

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[September 25, 2019]

By Alex Dobuzinskis [September 25, 2019]

By Alex Dobuzinskis

(Reuters) - Segregation in U.S. public education

has concentrated black and Hispanic children into high-poverty schools

with few resources, leading to an achievement gap between minority and

white students, a nationwide study showed on Tuesday.

Stanford University Graduate School of Education professor Sean Reardon

and his team crunched hundreds of millions of standardized test scores

from every public school in the United States from 2008 to 2016 to reach

their conclusions.

The findings reinforced previous studies illustrating that poverty,

linked to continuing segregation, is a key mechanism accounting for

racial disparities in academic achievement.

"If we want to improve educational opportunities and learning for

students, we want to get them out of these schools of high-concentrated

poverty," Reardon said in presenting his findings at Stanford on

Tuesday.

"Part of the reason why we have a big achievement gap is that minority

students are concentrated in high-poverty schools, and those schools are

the schools that seem systematically to provide lower educational

opportunities," he said.

African-American and Hispanic students tend to score lower on

standardized tests than white students, and closing that achievement gap

has posed a persistent challenge for educators.

The U.S. Supreme Court in its landmark 1954 decision in Brown v. Board

of Education ruled that racial segregation was a violation of the equal

protection clause of the U.S. Constitution's 14th Amendment.

In the decades that followed, public education officials wrestled with

how to integrate schools in the face of opposition by residents and

politicians in many regions.

This history became a point of contention between Democratic

presidential candidates during a televised debate in June, when U.S.

Senator Kamala Harris criticized former Vice President Joe Biden for his

1970s opposition to court-ordered busing to reduce segregation.

[to top of second column]

|

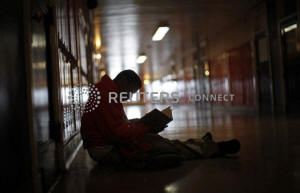

A student at Leo Catholic High School sits in the hallway as he

looks through a text book in Chicago, Illinois February 14, 2013.

REUTERS/Jim Young

In a working paper released on Monday, Reardon and his team compared

different levels of racial disparities between schools in New York

City and those in Fulton County, Georgia, to explain how segregation

affected student performance.

The school attended by the average black student in New York City

over a recent span of eight years had a poverty rate 22 percentage

points higher than that of the average white student. There

researchers found white students performing 2-1/2 grade levels above

black students on average.

By comparison, the average black student attended a school with a

poverty rate 52 percentage points higher than the average white

student's school in Fulton County, where an achievement gap of four

grade levels separated black and white students.

Gary Orfield, co-director of the Civil Rights Project at the

University of California, Los Angeles and not affiliated with the

Stanford study, endorsed the methodology Reardon's team used but

said its findings reveal only part of the picture.

"It's really misleading to talk about whether race or poverty is

most important, because a lot of the poverty is caused by race, and

that's something that people need to keep in mind," Orfield said.

For instance, discrimination against minority parents is a factor in

why those families are more likely to struggle with poverty, Orfield

said by telephone.

The Stanford research data is publicly available at the website

edopportunity.org.

(Reporting by Alex Dobuzinskis in Los Angeles; Editing by Steve

Gorman and Darren Schuettler)

[© 2019 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

Copyright 2019 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |