Special Report: Almost Home - COVID-19 ensnares elderly ICE detainee

from Canada

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[August 14, 2020]

By Mica Rosenberg [August 14, 2020]

By Mica Rosenberg

NEW YORK (Reuters) - James Hill often told

his family he just wanted to live moment to moment, like a Buddhist

monk. He said it was the only way to survive 14 years in prison after

being given a sentence he believed was unjust. But as his release date

neared this spring, his nieces and nephews started encouraging their

72-year-old "Uncle Jim" to start thinking about the future.

During his years in prison, Jim had refused visits because they would be

too painful, reminding him of the life he had left behind as a family

doctor in Louisiana. But as the months ticked closer to the end of his

sentence for healthcare fraud and distributing controlled substances,

including OxyContin, his family convinced him that a visit could be the

first step toward what his nephew Doug Hunt liked to call his "new

life."

"In our minds, now was the time to start prepping emotionally for him to

say, 'OK, yeah, we're here, this is real,'" said Doug's brother, David.

They and some of their cousins have kept in close contact with their

uncle over the years, especially after Jim's surviving siblings died

while he was in prison.

When David and his sister arrived in the heavily guarded visitation room

at Rivers Federal Correctional Institute in North Carolina in December

last year to see their uncle for the first time since his imprisonment,

they were told that no touching was allowed.

"As soon as he got within a foot of us, we said the hell with it and we

both hugged him together and didn't let go for 15 minutes," David said.

"We weren't supposed to do it, but the guards just let it go," granting

the elderly prisoner some leeway.

Soon they were all reminiscing, and Jim was cracking jokes. "We thought

we might be going there to try and heal him, but it was not that way –

he was healing us."

After the visit and the subsequent phone calls, Jim started feeling

hopeful about getting out, David said. The family converted the basement

in his late sister's house to a little apartment with its own bathroom

and kitchen area with a microwave and small fridge so that he would have

a place to call his own. They pooled their resources to gather

everything he would need: clothes, shoes, a computer, even a wallet.

They started making plans to see baseball games, take bike rides, go

sailing.

Then came the day he finally left prison. April 15.

But there was a problem. Jim wasn't a U.S. citizen. He was a Canadian

with a green card, which had allowed him to practice medicine in the

United States. Instead of immediately returning to his home country upon

his release, as he had hoped, he was shackled and transferred to a U.S.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention center in Virginia

to await an official deportation order from a judge.

An ICE spokeswoman said an order to transfer Jim to immigration

officials, known as a "detainer," was issued in his case in 2017 and a

copy of those orders are provided to federal inmates.

But his nephew Doug said Jim still didn't think he would be taken into

an ICE detention center. "He didn't realize that was going to happen,"

Doug said. "He was a free man and still a prisoner."

PAIN MANAGEMENT

Jim was in his 20s and the single father of two children when he decided

to go to medical school at the University of Toronto, according to one

of his daughters, Verity Hill. Saddled with thousands of dollars in

student loans after graduation, he answered the call of recruiters

looking for doctors and nurses to move to communities in the United

States, said nephew Doug. Jim had two more kids with a second wife, but

they split up and she returned to Canada when the children were small,

Doug said.

Jim was practicing as a family doctor in Shreveport, Louisiana, in 2006

when a warrant was issued for his arrest. A patient claimed she paid

$100 for an office visit but received a prescription for narcotics from

Jim's office manager without being examined, according to an affidavit

from an FBI agent supporting the warrant.

A subsequent indictment charged Jim with 80 counts of distribution of

controlled substances for signing prescriptions for at least two dozen

people without "a legitimate medical purpose," and 32 counts of

healthcare fraud for overbilling health insurance companies, according

to court documents. The indictment also said Jim had improperly

backdated a prescription. Prosecutors later alleged that the patient who

received that prescription died more than a year later from an overdose

of medications.

Jim, who had been in Canada, came back to turn himself in, thinking it

was all a misunderstanding that would soon be resolved, according to his

family members and letters he wrote at the time. He said his only goal

was to ease his patients' pain. His attorneys planned to introduce

expert testimony that would say his prescriptions were medically

appropriate and that he couldn't be held responsible for patients' abuse

of narcotics, court documents showed.

"I have committed no crime. I will be fully exonerated," Jim wrote Doug

from prison on April 3, 2006. "As you said, strange places can sometimes

provide a fulcrum for great changes. Right now I'm being small and still

and letting breath carry me through the tenses while trying to melt into

now."

But Donald Washington, the U.S. Attorney for the Western District of

Louisiana, had a different view. Washington said in a press release the

case demonstrated how "even medical doctors can become common

criminals."

By the end of 2006, after months in jail, Jim decided to plead guilty to

one count of healthcare fraud related to improperly billing for office

visits and one of distributing a controlled substance. On Christmas Day

2006, he wrote to his niece Jessica Marostega saying he had come to

believe it was wise to take the deal because juries were unpredictable

and the judge had partially limited what the expert witness could say in

court. "Thus, in the balance of things, I acquiesced," he wrote to his

niece, who goes by Jess.

"I am being depicted in the local newspapers and television as a

despicable common criminal and yet believe it or not, I feel blessed,"

he said in the letter to Jess. "Within each shell of anxiety and discord

there is a seed of peace and grace," he wrote, signing off, "May the

true spirit of Christmas penetrate your bones ... and warm you from

within when the world is cold."

With no prior criminal record, Jim thought his sentence wouldn't be that

long and told his family he expected to be home by late 2008 or early

2009.

Instead, U.S. District Judge S. Maurice Hicks decided to sentence Jim,

who was 59 at the time, to more than 16 years in jail. At the time of

the sentencing, Hicks said that Jim's explanations for his actions were

"little more than a low grade of baloney." Contacted recently, Hicks and

the U.S. Attorney's office in Louisiana that prosecuted the case said

they had no comment on the matter.

Randal Fish, one of Jim's attorneys, said he was "floored" by the

sentence. "It was an easy political move. They wanted to make a

statement about doctors prescribing pain medication," Fish said. "This

guy was not a citizen, it was easy to hammer him, and it was just truly

unfortunate."

"THESE FOUR WALLS"

In 2012 and then again in 2015, the U.S. Justice Department denied Jim's

requests to be transferred to Canada because his long residency made him

a "domiciliary" of the United States, according to family members and a

copy of a denial letter. The Justice Department said it could not

comment on international transfers because of privacy reasons.

With dwindling hopes of release, he tried to adjust to life in prison.

The early years were hard.

"These four walls close in sometimes and the noise is unbelievable," he

wrote Jess in June 2006.

After he said he had been transferred to a different federal prison, he

wrote Jess again in May 2007: "The food here is disgusting," complaining

of a serious salmonella outbreak. "A food worker told me the fish

patties served are labeled 'not for human consumption.' It is apparently

used to feed dolphins who are trained by the U.S. military in the

Persian Gulf to hunt for sea mines. Maybe I'll become as smart as a

dolphin and learn to communicate using sonar!"

"I am just taking one breath at a time during this period of

adaptation," he said in the letter. The Federal Bureau of Prisons

declined to comment.

He tried to focus on the positive. He had access to a small library and

a few courses such as leather-crafting and guitar, he wrote in the

letter. Over the years, he deepened his interest in Eastern medicine,

wrote drafts of books on wellness and would help other prisoners with

acupressure or simple advice on how to eat better to help control

diabetes or other chronic illnesses, nephew David said.

When Jim finally agreed to a visit as his sentence neared its end, David

was worried that his uncle would have a hard time seeing loved ones

after so long, but he was amazed at his attitude.

"Jim didn't seem like a broken man," David said. "He had enthusiasm for

life."

[to top of second column]

|

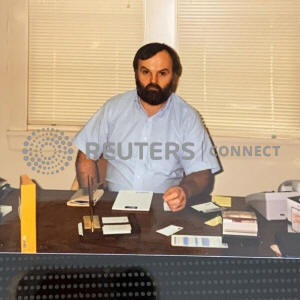

James Hill, a Canadian man who died August 5, 2020, of COVID-19

after being held for months in ICE custody in the Farmville

detention center in Virginia, U.S., is seen in this undated handout

photo. From James Hill's family/Handout via REUTERS

HIGH RISK

Just as Jim began to emotionally prepare for his release and return

to Canada, the coronavirus began spreading across the globe.

By the time he was transferred to the Farmville immigrant detention

center in mid-April, the protocol was to quarantine him for 14 days.

According to ICE guidance issued on April 10, all new detainees were

supposed to be evaluated to see if they were at higher risk for

serious illness from COVID-19, including if they were 65 or older.

The ICE spokeswoman didn't respond to a question about whether Jim

was evaluated and said only that he was subject to mandatory

detention.

As soon as Jim was moved out of isolation and into general

population, he called his family in a panic, they said. He was

terrified about catching COVID-19 in the communal dormitories, where

more than 80 detainees were packed together, sleeping on bunkbeds.

At one point, he stopped eating to avoid going to the crowded mess

hall and would try to sleep when everyone else was awake and stay

awake at night to limit his interactions, his nieces and nephews

said.

On May 3, his family wrote an urgent message to the Canadian Embassy

in Washington, D.C., requesting assistance deporting Jim as soon as

possible.

The consulate responded that it had been in touch with ICE to

express concerns about Jim's risk factors and advanced age, but said

the process of issuing his travel documents and passport could begin

only once he had an official order of removal from a U.S.

immigration judge.

A judge issued the deportation order on May 12, according to the

Executive Office for Immigration Review, which runs the immigration

court system. Then the process of obtaining Jim's travel documents

began.

On June 2, ICE transferred more than 70 detainees into Farmville

from Florida and Arizona. More than half of the transferees ended up

testing positive for the coronavirus.

Within weeks, the center would be engulfed with cases, and nearly

every detainee would be infected with the virus.

The delays were mystifying and infuriating for some of Jim's family.

"Ironically, most of the people in there were trying to stay in the

United States, whereas my uncle wanted to get the hell out," Doug

said. "It's like this perfect storm of things and we are all going,

'This can't be happening – the guy is like a week away from getting

out of there.'"

By mid-June, ICE had received Jim's travel documents, according to

emails between his family and Canadian consular officials. By then,

there were dozens of confirmed cases of COVID-19 at the center and

the detainees were getting increasingly agitated. Jim was told his

flight home was scheduled for July 9.

On July 1, after a disturbance among detainees, guards shot OC

pepper spray into the dorm where Jim was being held. Though he said

he received significant exposure to the chemicals, he told his

family that no one was allowed to leave the dorm to shower right

away. A spokesman for the detention center said deployment of the

spray was limited and every detainee who had been exposed was

examined by a nurse afterward.

The next day, officials at the center expanded testing for the

coronavirus to all detainees.

The results were still pending when Jim started feeling seriously

ill. He told his family he was taken to the hospital for a few hours

for evaluation but was then returned to the general dorm when he got

back to Farmville, against a recommendation from the doctor to put

him in medical isolation. The doctor had told him his difficulty

breathing and fatigue was likely caused by pepper-spray exposure or

COVID-19 or both, he told them. His condition so worsened overnight

that he had to be taken in a wheelchair to the medical unit.

As July 9 neared, Jess was waiting by the phone. She knew she could

get a call any minute to pick her uncle up from the airport. To

prepare for his arrival, she bought streamers and welcome-home

balloons and chocolates and bottles of red wine, his favorite.

The day before he was supposed to fly out, the family received an

email from the Canadian Embassy. Unfortunately, his travel has been

postponed due to medical concerns, the consular officer wrote,

saying, "I'm sorry I don't have better news."

"LOST CHANCES"

By July 10, there were more than 100 confirmed cases of COVID-19 at

Farmville. Jim had been calling his family every day. Then suddenly,

the calls stopped. "We were emailing each other seeing if anyone had

heard from him," said Doug, who was in constant communication with

his siblings and cousins about their uncle's case. "We had no idea

where he was."

Days went by. His family called Farmville but were told they could

only pass a message to Jim and that their uncle needed to update his

consent form before any information could be released to them.

Eventually, the family said, the consulate was able to locate him.

He had tested positive for the coronavirus and had indeed been

hospitalized. The Canadian consular officer who was helping the

family was able to speak with Jim and talk to his doctors, and

subsequently helped his nieces and nephews to talk to their uncle

and his medical providers. The ICE spokeswoman said detainees aren't

usually allowed to call family during hospital stays for security

purposes but that an exception was made in this case, allowing Jim's

family to be in direct contact with him starting July 21.

He was soon placed on a ventilator.

On August 5, after being held in ICE custody for nearly four months,

Jim died.

ICE said in a statement that it was undertaking "a comprehensive,

agency-wide review of this incident, as it does in all such cases,"

and that fatalities in ICE detention – where around 21,000

immigrants are being held – are "exceedingly rare." The agency said

it has "taken extensive precautions" to limit the spread of the

virus and "ensures the provision of necessary medical care."

There have been more than 4,500 cases of COVID-19 detected so far in

immigration detention centers around the country, and five detainees

have died from the disease, according to ICE. One of them was a

70-year-old Costa Rican detainee in Georgia who died from COVID-19

complications on Aug. 10, the agency said in a statement.

The ICE spokeswoman said the agency makes every effort to remove

detainees expeditiously and works to coordinate the process with the

receiving country to ensure they are cleared to travel. A

spokeswoman for Canada's Global Affairs office said in a statement

that consular officials were assisting the family and were in

contact with local authorities to gather additional information.

Jim's daughter Verity said her dad had four grandchildren and three

great-grandchildren. After he died, she wrote down some thoughts

about what she had hoped would happen when she finally saw him

again.

"I had planned a gentle reunion. I would bring the grandkids, and

great-grandkids if I could," she said. "I'd clasp your hands, look

into your eyes, and just smile. You'd know. We wouldn't have to word

it. And we'd spend the rest of our lives quietly close, knowing."

Verity said she was struck by an excerpt from a poem her father had

written earlier this year:

will we now grieve for our lost chances?

will we cower in fear of punishment?

or will we greet our finality with

the expectant joy of a newborn child

and summon the courage to awaken

(Reporting by Mica Rosenberg, editing by Kari Howard)

[© 2020 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2020 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |