|

The large display according to young Fred Suffold is

a reflection of not just the life of black Americans but also a look

at the civilization prior to slavery, and to the societies of

Africans prior to being brought to America in bondage. The large display according to young Fred Suffold is

a reflection of not just the life of black Americans but also a look

at the civilization prior to slavery, and to the societies of

Africans prior to being brought to America in bondage.

The collection also looks at some of the lesser known figures in

black history, as well as the well-known and those who have achieved

greatness in a variety of venues.

The collection came to Lincoln from Detroit,

Michigan. It is part of a large private collection belonging to the

Suffold family. The senior Fred Suffold started collecting many

years ago and the display is now being offered to the public through

the work of his son Fred and daughter Janay Craft.

According to the junior Fred Suffold, the museum has visited 24

states and been viewed by more than 50,000 visitors. He said that

sharing black history was quite important to his father, and now the

son and daughter are working to deliver their father’s message

through the artifacts and memorabilia of their ancestry.

The collection begins with some beautiful pieces of

functional art from Ghana and Mali. The Kente and Mudcloth according

to the display notes are pieces that “communicate a sense of African

Pride and esteem.” Suffold said it was important for people to see

that prior to slavery, the African people had their own

civilizations and a sense of community.

The next array on the table was an item from the late

1700’s. A set of slave shackles spoke to the bondage of African

people when they were brought to America and forced to serve as the

workforce on southern plantations.

The museum displays go on to show historical figures of the slavery

era including Fredrick Douglas, a well-known historical figure and

two lesser known individuals.

Carter G Woodson authored the Journal of Negro

History in 1916.

Blanche Kelso Bruce was born a slave in 1841 in Missouri. Kelso fled

to Kansas in search of his freedom and then after the civil war

returned to Missouri to found the first African American School in

the community of Hannibal. Bruce was also the first African American

to serve in the U.S. Senate.

The display includes other notable historical figures, such as

Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks and Malcom X.

But it also includes the teacher certificate for

Willa Mae Robinson, who was granted the right to teach in the state

of North Carolina in 1927.

[to top of second column] |

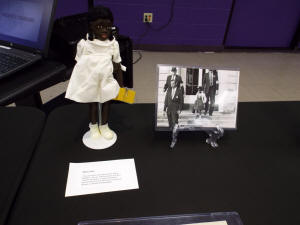

The display also includes the Wilma Doll, a doll

endorsed by Norman Rockwell and modeled after his painting “The

problem we all live with.”

That painting, done in 1964 by the famous artist reflects a young

girl Ruby Bridges, a six-year-old African American girl, on her way

to William Frantz Elementary School, an all-white public school, on

November 14, 1960. Because of the threats on her life for attending

an all-white public school, Ruby was escorted to and from school by

U.S. Marshals.

Along with the doll is a photo of Ruby Bridges exiting her school

being escorted by the marshals.

Other displays included items from the Black

Panthers, Oprah Winfrey and Aretha Franklin. A Tuskegee Airman doll

is also on display along with a singed photo of Charles McGee an

Airman and career officer in the U.S. Air Force who holds the record

of 409 combat missions flown across three wars, World War II, Korea

and Vietnam.

There is also photos of Robert Lawrence, Jr., the

first African American astronaut.

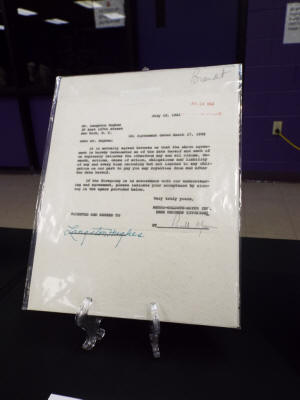

Local connections within our black history were also reflected in

the display as Langston Hughes is featured, including a photo of the

author at his typewriter and a release agreement between Hughes and

Metro-Goldwyn-Myer MGM Records Division, signed by Hughes.

Throughout the four hours that the museum was set up at Lincoln

College, several visitors stopped including students, members of the

community and Lincoln College staff.

The museum was brought to Lincoln College by the Lynx

Activity Board. Members of that group visited with guests as they

arrived encouraging everyone to enjoy the displays.

Black History Month offers us all an opportunity to celebrate the

achievements by African Americans and their role in U.S. history.

The month-long celebration held each year in February is the

successor of “Negro History Week,” an observation brought to us by

the same Carter G. Woodson mentioned earlier as the author of the

Journal of Negro History published in 1916.

[Nila Smith]

|