Grief in a pandemic: Holding a dying mother's hand with a latex glove

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[March 28, 2020]

By Deborah Bloom and Nathan Layne [March 28, 2020]

By Deborah Bloom and Nathan Layne

KIRKLAND, Wash. (Reuters) - Doug Briggs put

on a surgical gown, blue gloves and a powered respirator with a hood. He

headed into the hospital room to see his mother - to tell her goodbye.

Briggs took his phone, sealed in a Ziplock bag, into the hospital room

and cued up his mother's favorite songs. He put it next to her ear and

noticed her wiggle, ever so slightly, to the music.

"She knew I was there," Briggs recalled, smiling.

Between songs by Barbara Streisand and the Beatles, Briggs

conference-called his aunts to let them speak to their sister one last

time. "I love you, and I'm sorry I'm not there with you. I hope the

medicine they're giving you is making you more comfortable," said Meri

Dreyfuss, one of her sisters.

Somewhere between "Stand by Me" and "Here, There, and Everywhere,"

Barbara Dreyfuss passed away – her hand in her son's, clad in latex. It

would be two days before doctors confirmed that she had succumbed to

COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

Dreyfuss, 75, was the eighth U.S. patient to die in a pandemic that has

now killed more than 1,200 nationally and nearly 25,000 worldwide. She

was among three dozen deaths linked to the Life Care nursing home in

Kirkland, Washington, the site of one of the first and deadliest U.S.

outbreaks. (For interactive graphics tracking coronavirus in the United

States and worldwide, click https://tmsnrt.rs/2Uj9ry0 and https://tmsnrt.rs/3akNaFr

)

Dreyfuss's final hours illustrate the heartrending choices now facing

families who are forced to strike a balance between staying safe and

comforting their sick or dying loved ones. Some have been cut off from

all contact with parents or spouses who die in isolation, while others

have strained to provide comfort or to say their final goodbyes through

windows or over the phone.

Just three days before his mother died, Briggs had been making weekend

plans with her. Now, in his grief, he found himself glued to news

reports and frustrated by the mixed messages and slow response from

local, state and federal officials.

"You find out all these things, of what they knew when," Briggs said.

Officials from Life Care Centers of America have said the facility

responded the best it could to one of the worst crises ever to hit an

eldercare facility, with many staffers stretched to the brink as others

were sidelined with symptoms of the virus. As the first U.S. site hit

with a major outbreak, the center had few protocols for a response and

little help from the outside amid national shortages of test kits and

other supplies.

'NOT FEELING TOO GOOD'

A flower child of the 1960's, Dreyfuss lived a life characterized by art

and activism. After marrying her high school sweetheart and giving birth

to their son, she pursued a degree in women's studies at Cal State Long

Beach, where she marched for women's equality and abortion rights.

Furious over President Gerald Ford's pardoning of former president

Richard Nixon in 1974, Dreyfuss took to her typewriter and penned an

angry letter to Ford. "Today is my son's 9th birthday," she wrote of a

young Briggs. "I do not feel like celebrating."

By the time she arrived at the Life Care Center in May 2019, years of

health issues had dimmed some of that spark, her son said. Fibromyalgia

and plantar fasciitis restricted her to a walker or a wheelchair, and

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease required her to have a constant

flow of oxygen.

When her son visited on Feb. 25, he brought a grocery bag of her

favorites, including diet A&W root beer. She awoke from a nap and smiled

at him, but hinted at her discomfort.

"Hi Doug," she said. "I'm not feeling too good."

Still, Dreyfuss talked about an upcoming visit with her sisters - the

movies she wanted to see, the restaurants she wanted to try. The mother

and son then had only a vague awareness of the deadly virus then

ravaging China.

[to top of second column]

|

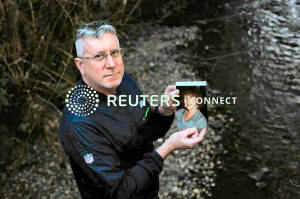

Doug Briggs poses for a portrait with an old picture of his mother,

Barbara Dreyfus, who was a resident at Life Care Center of Kirkland,

contracted coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and later died in a

hospital, near a creek she enjoyed outside of her old home in

Kirkland, Washington, U.S., March 16, 2020. REUTERS/David Ryder

In hindsight, Briggs realized he had witnessed the first signs of

her distress. His mother was using more oxygen than usual, her

breathing was more strained.

At the time, staff at the nursing home believed they were handling a

flu outbreak and were unaware the coronavirus had started to take

hold, a spokesman has said.

'A TINY FOOTNOTE'

Two days later, Briggs dropped by to see his mom. She felt

congested, and staff were going to X-ray her lungs for fluid.

Briggs, 54, still saw no red flags, and continued to discuss weekend

plans with his mother.

"I hope we can finally watch that new Mr. Rogers movie," she told

him, referring to the film, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood.

Briggs hugged his mom before she was wheeled to the imaging room and

drove for a quick meal. Soon after, he received a call from the

nursing home. His mother was experiencing respiratory failure. She

was on her way to the hospital. Doug rushed to nearby

EvergreenHealth Medical Center. By then, she was unresponsive.

At the time, there were 59 U.S. cases of coronavirus, a number that

has since soared to more than 85,000.

After hearing of her sister's sudden hospitalization, Meri Dreyfuss

remembered an earlier voicemail from Barbara: her distant voice,

groaning for 30 seconds. When she had first heard it, she assumed

Dreyfuss had called by accident, but now she realized her sister was

in pain. "It haunts me that I didn't pick up the phone," she said.

Briggs spent close to 10 hours the next day in his mom's hospital

room. He wore a medical mask and anxiously watched her vital signs –

especially the line tracking her oxygen saturation.

On his way out the door, a doctor took him aside to say they were

testing her for the coronavirus. He remembered the difficulty

reconciling the outbreak taking place on television - far away, in

China - with what was happening in his mother's hospital room.

In the Bay Area, Meri and Hillary Dreyfuss were packing their

suitcases on Feb. 28 when Briggs telephoned. After the call, they

decided that visiting their sister would pose too much danger of

infection.

"I realized there was no way we were going to get on a plane at that

point, because we couldn't see her," said the middle sister,

Hillary. "And now, it seemed that we shouldn't be seeing Doug,

either."

They canceled their flights. On Saturday, Feb. 29, Briggs learned

his mother's condition was deteriorating. Tough decisions loomed.

Briggs and his aunts decided to prioritize making her comfortable

over keeping her alive. Doctors gave her morphine to relax the

heaviness in her lungs.

She died the next day.

Having emerged from a two-week quarantine, Briggs will soon retrieve

his mother's cremated remains. The family has been struggling with

how to memorialize her life in such chaotic times.

"All the things that one would want to happen in the normal mourning

process have been subsumed by this larger crisis," said Hillary

Dreyfuss. "It's almost as though her death has become a tiny

footnote in what's going on."

(Reporting by Deborah Bloom and Nathan Layne; Editing by Paul

Thomasch and Brian Thevenot)

[© 2020 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2020 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |