Childhood vaccine linked to less severe COVID-19, cigarette smoke raises

risk

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[November 21, 2020]

By Nancy Lapid [November 21, 2020]

By Nancy Lapid

(Reuters) - The following is a roundup of

some of the latest scientific studies on the novel coronavirus and

efforts to find treatments and vaccines for COVID-19, the illness caused

by the virus.

Childhood vaccine may help prevent severe COVID-19

People whose immune systems responded strongly to a

measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine may be less likely to become

severely ill if they are infected with the new coronavirus, new data

suggest. The MMR II vaccine, manufactured by Merck and licensed in 1979,

works by triggering the immune system to produce antibodies. Researchers

reported on Friday in mBio that among 50 COVID-19 patients under the age

of 42 who had received the MMR II as children, the higher their titers

-- or levels -- of so-called IgG antibodies produced by the vaccine and

directed against the mumps virus in particular, the less severe their

symptoms. People with the highest mumps antibody titers had asymptomatic

COVID-19. More research is needed to prove the vaccine prevents severe

COVID-19. Still, the new findings "may explain why children have a much

lower COVID-19 case rate than adults, as well as a much lower death

rate," coauthor Jeffrey Gold, president of World Organization, in

Watkinsville, Georgia, said in a statement. "The majority of children

get their first MMR vaccination around 12 to 15 months of age and a

second one from 4 to 6 years of age."

Cigarette smoke increases cell vulnerability to COVID-19

Exposure to cigarette smoke makes airway cells more vulnerable to

infection with the new coronavirus, UCLA researchers found. They

obtained airway-lining cells from five individuals without COVID-19 and

exposed some of the cells to cigarette smoke in test tubes. Then they

exposed all the cells to the coronavirus. Compared to cells not exposed

to the smoke, smoke-exposed cells were two- or even three-times more

likely to become infected with the virus, the researchers reported on

Tuesday in Cell Stem Cell. Analysis of individual airway cells showed

the cigarette smoke reduced the immune response to the virus. "If you

think of the airways like the high walls that protect a castle, smoking

cigarettes is like creating holes in these walls," coauthor Brigitte

Gomperts told Reuters. "Smoking reduces the natural defenses and this

allows the virus to enter and take over the cells."

[to top of second column]

|

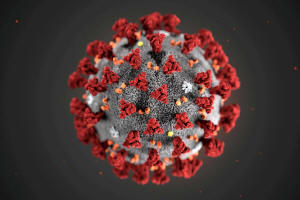

The ultrastructural morphology exhibited by the 2019 Novel

Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), which was identified as the cause of an

outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in Wuhan, China, is

seen in an illustration released by the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. January 29, 2020.

Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM/CDC/Handout via REUTERS.

AstraZeneca's COVID-19 vaccine shows promise in elderly

AstraZeneca and Oxford University's experimental COVID-19 vaccine

produced strong immune responses in older adults in a mid-stage

trial, researchers reported on Thursday in The Lancet. Late-stage

trials are underway to confirm whether the vaccine protects against

COVID-19 in a broad range of people, including those with underlying

health conditions. The current study involved 560 healthy

volunteers, including 240 age 70 or over. Volunteers received one or

two doses of the vaccine, made from a weakened version of a common

cold virus found in chimpanzees, or a placebo. No serious side

effects were reported. Participants older than 80, frail patients,

and those with substantial chronic illnesses were excluded,

according to an editorial published with the study. "Frailty is

increasingly understood to affect older adults' responses to

vaccines," the editorialists write. "A plan for how to consider

frailty in COVID-19 vaccine development is important."

Researchers look into cells infected with new coronavirus

Cells infected with the new coronavirus die within a day or two, and

researchers have found a way to see what the virus is doing to them.

By integrating multiple imaging techniques, they saw the virus

create "virus-copying factories" in cells that look like clusters of

balloons. The virus also disrupts cellular systems responsible for

secreting substances, the researchers reported on Tuesday in Cell

Host & Microbe. Furthermore, it reorganizes the "cytoskeleton,"

which gives cells their shape and "serves like a railway system to

allow the transport of various cargos inside the cell," coauthor Dr.

Ralf Bartenschlager of the University of Heidelberg, Germany told

Reuters. When his team added drugs that affect the cytoskeleton, the

virus had trouble making copies of itself, "which indicates to us

that the virus needs to reorganize the cytoskeleton in order to

replicate with high efficiency," Bartenschlager said. "We now have a

much better idea how SARS-CoV-2 changes the intracellular

architecture of the infected cell and this will help us to

understand why the cells are dying so quickly." The Zika virus

causes similar cell changes, he said, so it might be possible to

develop drugs for COVID-19 that also work against other viruses.

(Reporting by Nancy Lapid, Kate Kelland and Alistair Smout; Editing

by Tiffany Wu)

[© 2020 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2020 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |