Special Report: Will your mail ballot count in the U.S. presidential

election? It may depend on who's counting and where

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[September 25, 2020]

By Julia Harte, Jason Lange and Simon Lewis [September 25, 2020]

By Julia Harte, Jason Lange and Simon Lewis

(Reuters) - Two elderly women in small

towns in Wisconsin voted by mail during April’s presidential nominating

contests. Both were sheltering in place as coronavirus surged across

their state.

Each mailed her ballot to the local election office with a note

explaining why no witness had signed the envelope, as Wisconsin’s strict

voting laws require. The women didn’t want to risk virus exposure, they

told Reuters in telephone interviews this month.

That’s where the similarity ends. The ballot of Peggy Houglum, a

72-year-old voter in the eastern Wisconsin hamlet of Cedar Grove, was

rejected due to the missing witness information. That of Judith Olson,

88, a resident of the northern town of Elk, was accepted, according to

“incident” logs viewed by Reuters in which Wisconsin election offices

document irregular ballots. Houglum, who plans to vote for Democratic

presidential candidate Joe Biden in November, said she was never told

her ballot didn’t count. Olson wouldn’t provide her party affiliation or

say whom she supports for president.

Local election officials confirmed the fate of those ballots. Cedar

Grove Village Clerk Julie Brey told Reuters she had sought guidance from

the Wisconsin Elections Commission on what to do. Her Elk counterpart,

Suzanne Brandt, said she couldn’t recall who advised her to accept an

unwitnessed ballot.

The unequal treatment in the same crucial battleground state underscores

a growing worry about the general election on Nov. 3 between Biden and

incumbent Republican President Donald Trump. Whether or not a mail

ballot is counted could depend to a large degree on how local election

workers enforce mail-in voting rules, how they notify voters who submit

deficient ballots, and whether they allow them to fix such errors. Each

of the 50 U.S. states has a central election authority, but ballots are

processed by dozens of separate county or municipal election offices

within each state.

Reuters reviewed incident logs and other election records from

Wisconsin’s April race. The news organization also examined data from

election offices in North Carolina, Florida and Arizona containing the

number of mail-in ballots rejected in recent elections in those

presidential battlegrounds. Reuters also surveyed 36 election officials

across the four states about how they processed mail-in ballots,

notified voters who mailed deficient ballots, and enabled those voters

to cast valid votes.

The records detailed more than 3 million mail ballots cast during the

four states’ presidential nomination contests this year. The vast

majority of those were accepted, but at least 25,000 mail-in ballots

were rejected for violations of signature and witness requirements.

Reuters could not follow up with all individuals whose ballots were

rejected. Still, some trends emerged from the statewide data and

interviews with dozens of voters and election officials.

Reuters found:

- Minorities, who tend to vote Democratic, are more likely than white

voters to have their mail-in ballots rejected for signature and witness

issues in North Carolina and Florida. Voter race data was unavailable in

Arizona and Wisconsin.

- Procedures for handling deficient mail ballots differed, sometimes

markedly, between election offices within each state; and election

officials told Reuters of varying timetables and methods for notifying

voters. Ballot designs also diverged, with signature boxes clearer on

some than others.

- Geography and population size helped determine how easily election

officials could contact voters about ballot deficiencies. Officials in

small, compact jurisdictions tended to say they found it easier to

notify voters than did their counterparts in larger communities, because

they were more likely to know voters personally.

(For a graphic on ballot rejections in four battleground states, see

https://tmsnrt.rs/3mLFOl8)

'VOTING WITHOUT A SAFETY NET'

U.S. mail-in voting surged in states that held presidential primaries

after mid-March, when the COVID-19 pandemic exploded. Millions of

Americans are projected to cast mail ballots for the first time this

November, with coronavirus expected to drive record-high absentee

turnout.

Slowed U.S. Postal Service deliveries this summer raised alarms about

ballots arriving too late to be counted. But voters may not be aware of

other potential pitfalls.

The uneven application of mail-in voting rules illegally disadvantages

some voters, according to voting-rights advocates, who have sued to

standardize the way local officials process absentee ballots, notify

voters about errors and allow voters to fix them in the four states that

Reuters examined. One lawsuit failed in September to eliminate

Wisconsin’s witness requirement. Another successfully extended the

period for Arizona voters to add signatures to unsigned ballots.

Activists won settlements in two additional cases, one in Florida, the

other in North Carolina, though they say those states have yet to comply

fully.

For millions of U.S. voters, voting-rights advocates say, the odds of

their mail-in ballot counting this November could come down to where

they are registered to vote and how workers in their local election

office implement their state’s voting rules.

"Mail-in voting is voting without a safety net," because voters are not

present to resolve any issues that arise with their mail ballots, said

David Becker, head of the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation &

Research. That underscores why statewide rules "shouldn’t be applied

differently county to county," he said.

Jason Snead, executive director at the conservative Honest Elections

Project, said election officials should apply absentee ballot

requirements as uniformly as possible. Still he said “absolute

uniformity” goes against the U.S. tradition of running elections locally

to provide “flexibility, responsiveness and direct accountability to

voters.” He said voters need to know they must "follow every rule that

is written out on that ballot, make sure that they've crossed every t,

dotted every i.”

The stakes are high.

Trump won the White House in 2016 by a whisker. He lost the popular

vote, but fewer than 80,000 votes in three crucial states, including

Wisconsin, handed him an Electoral College victory over Democrat Hillary

Clinton. Recent polls slightly favor Biden in Wisconsin, but he and

Trump are neck-and-neck in Florida, Arizona and North Carolina.

The number of rejected mail ballots is almost certain to be higher in

November than it was in this year’s primaries because of higher expected

turnout, election experts said.

In North Carolina, for example, about 1% of voters cast mail ballots in

the March 3 primary, before coronavirus swept the nation. That figure

could soar close to 25% in November, according to a Reuters/Ipsos poll

of likely voters conducted earlier this month. About a third of voters

in Florida expect to vote by mail, as do about two in five voters in

Wisconsin and more than half in Arizona, other Reuters/Ipsos polls

showed this month.

If officials in North Carolina and Florida alone toss out ballots in

November at the rates they did in March, more than 75,000 voters could

be disenfranchised, Reuters calculates. That figure assumes turnout

matches 2016 levels, and that voters end up casting mail ballots at the

levels they said they would in the polls.

(For a primer on mail-in voting in the United States, see: https://tmsnrt.rs/3ic6mt9)

TALE OF TWO BALLOTS

In the four battleground states, Reuters found examples of 24 voters

whose ballots were rejected without their knowledge, because local

authorities used different mail-in ballot counting processes or

notification procedures than other localities in the same state.

Election officials in almost every case claimed they had attempted to

notify voters who cast deficient ballots and informed them how to cast a

valid vote.

Wisconsin and North Carolina are among 11 U.S. states that require

absentee ballot envelopes to be signed by a witness.

More than half of the 23,000 absentee ballots rejected in Wisconsin’s

April 7 primary were thrown out for lacking a voter signature, witness

information or both, according to state data. On April 2, a federal

district judge in Wisconsin relaxed the witness requirement due to the

pandemic. That ruling was overturned by the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals

the next day.

Election officials statewide applied the witness requirement in myriad

ways, according to a Reuters analysis of incident logs and other public

records from municipalities comprising about 80% of Wisconsin’s

electorate.

In the eastern Wisconsin village of Waldo, home to around 500 people,

Clerk-Treasurer Michelle Brecht noticed a dozen voters had omitted

witness information on their mail ballots; witnesses must provide a

signature and an address. Because Brecht knew almost everyone in town,

she told Reuters, she contacted all affected voters and was able to help

them fix their ballots.

[to top of second column]

|

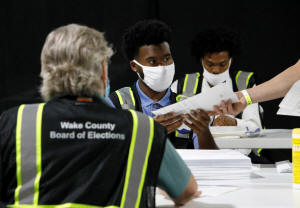

Poll workers prepare absentee ballots for shipment at the Wake

County Board of Elections on the first day that the state started

mailing them out, in Raleigh, North Carolina, U.S. September 4,

2020. REUTERS/Jonathan Drake

In the western Wisconsin town of Pepin, meanwhile, ballots lacking

voter signatures and witness information were among 143 mail votes

counted, according to County Board of Canvassers’ minutes from the

April primary. The minutes did not say how many mail ballots were

deficient, but the board recommended “more training for election

workers in the area of absentee ballot processing.”

Nancy Wolfe, town clerk of Pepin, whose population is a little more

than 800 residents, said her staff had received additional training.

She did not respond when asked specifically about the board’s claim

that deficient absentee ballots were accepted in the April primary.

Some inconsistencies likely arose from confusion over the

last-minute court rulings, according to Jay Heck, state director for

Common Cause Wisconsin, a government watchdog group. The appeals

court reversed the district court’s lifting of the witness

requirement just days before the election, he noted, leaving

election officials disoriented. Heck also pointed to Wisconsin’s

“unusually decentralized” election administration system, in which

1,850 separate municipalities handle voter registration and absentee

ballots.

North Carolina’s witness requirement is even stricter: Absentee

voters had to find two witnesses for the March 3 primary. That

tripped up retiree William Hearn. He told Reuters he only got one

witness to sign his ballot envelope. (For the November presidential

contest, North Carolina is allowing voters to secure a single

witness.)

Hearn, 72, was one of at least 121 voters in Durham County and

nearly 1,800 statewide who had mail-in ballots rejected for missing

signature or witness information, according to a Reuters analysis of

state election data.

Derek Bowens, director of the elections board of Durham County,

which contains North Carolina’s fourth-largest city, Durham, said

his office mailed a replacement ballot with a letter of explanation

to Hearn on February 27, one day after receiving his incomplete

ballot.

Hearn said he never received it and had no idea his original ballot

had been rejected until notified in September by Reuters. “I have a

very big problem with that,” Hearn said. A Biden supporter, he now

fears his mail ballot could be rejected in November without his

knowledge.

An hour south in Harnett County, Republican David Krachun, 57,

forgot to sign his ballot in the March primary. In contrast to

Durham, Harnett County voters who cast deficient ballots were

notified twice by mail and as many times as necessary by phone,

according to county elections director Claire Jones.

Of the 25 voters who had mail ballots rejected in Harnett County,

which is largely Republican, seven eventually cast a ballot that

counted, according to Jones; they included Krachun, who mailed in a

second absentee ballot that was accepted. Harnett County's 28%

"cure" rate was close to three times that of Durham County, a

Democratic stronghold.

RACIAL DISPARITIES

Krachun is white, while Hearn, whose ballot was rejected, is Black.

During the March election in North Carolina, about 5% of all voters

who returned mail ballots had them rejected for signature or witness

issues and ended up not casting a vote that counted, state election

records show. Broken down by race, about 8% of Black voters didn’t

wind up casting a valid vote after their mail ballots were tossed

compared to about 5% of white voters. Election officials interviewed

by Reuters had no explanation for the disparity.

Florida counties also reject mail-in ballots at widely varying

rates, and they reject Black and Hispanic voters at higher rates

than white voters, according to University of Florida professor

Daniel Smith.

Smith examined mail-in ballots in March’s presidential primary that

were recorded as being delivered by Election Day. Out of those

voters, 1.1% of Hispanics and 0.8% of Blacks had their ballots

rejected, Smith found, compared with just 0.4% of whites.

Officials in six Florida counties where minorities were rejected at

significantly higher rates than white voters said their offices

applied the rules consistently and that racial and ethnic

disparities must be due to factors outside their control.

“It's definitely not something purposely being done,” said Kari

Ewalt, community relations manager for the supervisor of elections

in Osceola County. Smith found that Hispanic voters there were more

than twice as likely as white voters to have their ballots rejected.

One possible explanation is that many minority voters have little

experience with mail voting. But Smith found that even accounting

for that, Black and Hispanic voters were more likely to have their

ballots rejected. The variation across Florida counties suggested

“it can’t just be the individual’s fault,” Smith said.

Disparities could arise from officials in some election offices

being stricter when scrutinizing a voter’s signature, Smith said.

The design of the ballot return envelope, and how quickly officials

process ballots and flag problems to voters, are also potential

factors, he said.

NO STANDARD PROCESS

Local election officials in all four states have considerable leeway

in how they process mail-in ballots and respond to errors.

In Florida, officials must contact voters whose ballots lack

signatures and offer them a chance to confirm their identities with

an affidavit, which can be returned up to two days after the polls

close. But there is no set prescription for how to do that. Some

election offices first try to call the voter, others first put the

affidavit in the mail. Others said they primarily use email.

In North Carolina, a Reuters survey of 20 counties revealed similar

differences. In rural Lee County, Karen Marosites, deputy director

of elections, said it sometimes took eight days to notify a voter of

a deficient mail-in ballot.

In response to a lawsuit brought by groups including the Southern

Coalition for Social Justice, a civil rights organization, a federal

judge in North Carolina in August ordered the state elections board

to publish statewide guidance that would bring the state’s 100

counties into alignment.

Coalition attorneys said the resulting guidance, released September

22, was an improvement but still lacked clarity on how counties

would help voters cure deficient ballots. The North Carolina

elections board did not respond to requests for comment.

In Wisconsin, a federal district judge in September upheld

Wisconsin’s witness requirement after the Democratic National

Committee sued to remove it due to the pandemic.

In Arizona, another lawsuit filed by the Democratic Party this year

prompted the state’s 15 counties to standardize how mail-in voters

could fix signature issues, giving them five business days after

Election Day to cure unsigned ballots and mismatched signatures. But

officials still have significant leeway in contacting voters.

Pima County, Arizona’s second-largest, mails replacement ballots

only to voters whose unsigned ballots arrive more than a week before

Election Day. Rural Apache County, meanwhile, notifies such voters

via phone, email and U.S. mail, and follows up at least twice with

phone and email if needed -- in addition to sending back the

unsigned ballot if there is enough time for voters to sign and

return it. “We have had people call us mad that we are ‘spamming’

them,” said Apache County Chief Deputy Recorder Bowen Udall.

Alex Gulotta, the Arizona state director of All Voting is Local, a

voting-rights group, said such differences can determine whether

votes count - or not.

“There shouldn’t even be a possibility for that much variance to

exist between the counties,” Gulotta said.

(Reporting by Julia Harte, Jason Lange and Simon Lewis in

Washington, D.C.; Editing by Marla Dickerson)

[© 2020 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2020 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |