Virus can damage brain without infecting it; hair loss on rise among

minorities during pandemic

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[January 07, 2021]

By Nancy Lapid [January 07, 2021]

By Nancy Lapid

(Reuters) - The following is a roundup of

some of the latest scientific studies on the novel coronavirus and

efforts to find treatments and vaccines for COVID-19, the illness caused

by the virus.

Coronavirus can damage the brain without infecting it

The new coronavirus does not need to directly invade brain tissue to

damage it, a new study suggests. Researchers examined the brains of 19

patients who died from COVID-19, focusing on tissues from regions

thought to be highly susceptible to the virus: the olfactory bulb, which

controls the sense of smell, and the brainstem, which controls breathing

and heart rate. In 14 patients, one or both of these regions contained

damaged blood vessels - some clotted, and some leaking. The areas with

leakage were surrounded by inflammation from the body's immune response,

they found. But the researchers saw no signs of the virus itself, they

report in The New England Journal of Medicine. "We were completely

surprised," said coauthor Dr. Avindra Nath of the National Institute of

Neurological Disorders and Stroke in a statement. The damage his team

saw is usually associated with strokes and neuroinflammatory diseases,

he said. "So far, our results suggest that the damage ... may not have

been caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus directly infecting the brain," Dr.

Nath said. "In the future, we plan to study how COVID-19 harms the

brain's blood vessels and whether that produces some of the short- and

long-term symptoms we see in patients."

Hair loss surges in NYC minority communities during pandemic

Pandemic stress may be causing people to lose their hair, according to a

new study. By mid-summer, rates of a hair-shedding condition called

telogen effluvium (TE) had surged more than 400% in a racially diverse

neighborhood in New York City, researchers report in the Journal of the

American Academy of Dermatology. From November 2019 through February

2020, the incidence of TE cases was 0.4%. By August, that rate had

climbed to 2.3%, they found. "It is unclear if the increase in cases of

TE is more closely related to the physiological toll of infection or

extreme emotional stress," said coauthor Dr. Shoshana Marmon of Coney

Island Hospital. The increase was due primarily to TE in persons of

color, particularly in the Hispanic community, "in line with the

disproportionately high mortality rate of this subset of the population

due to COVID-19 in NYC," the authors said. TE rates rose in smaller

non-white minorities as well, but not among Blacks, who also were

severely impacted by COVID-19. Dr. Adam Friedman of George Washington

School of Medicine and Health Sciences, who was not involved in the

research, said he too is seeing increases in TE "and the timing makes

plenty of sense, as the onset of shedding is typically three months

following the traumatic event," which would correspond to the rise of

the pandemic.

[to top of second column]

|

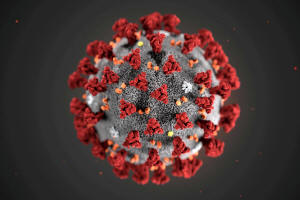

The ultrastructural morphology exhibited by the 2019 Novel

Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), is seen in an illustration released by the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta,

Georgia, U.S. January 29, 2020. Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM/CDC/Handout

via REUTERS.

Researchers argue for one vaccine dose to enhance supply

A single dose of one of the currently available COVID-19 vaccines,

even if less effective than two doses, may have greater population

benefit, three research groups argued on Tuesday in three papers in

Annals of Internal Medicine. In large trials, two-dose regimens of

the vaccine from Pfizer Inc and partner BioNTech SE and Moderna

Inc's shot both demonstrated nearly 95% efficacy in preventing

illness from the coronavirus. Yale School of Public Health

researchers say a less-effective single-dose might confer greater

population benefit than a 95%-effective vaccine requiring two doses.

University of Washington researchers say doubling vaccine coverage

by giving a single dose to more people would hasten pandemic control

by lowering transmission rates. Stanford University researchers say

delaying second doses in some people could enable millions more to

receive a vaccine. "In a public health emergency, a powerful

argument exists for doing something with less-than-perfect results

if it can help more persons quickly," said Thomas Bollyky of the

Council on Foreign Relations in an editorial published with the

papers. "However, whether alternative approaches with current

vaccines would accomplish this goal is far from clear." The U.S Food

and Drug Administration said on Monday the idea of changing the

authorized dosing or schedules of COVID-19 vaccines was premature

and not supported by available data.

(Reporting by Nancy Lapid and Marilynn Larkin; Editing by Bill

Berkrot)

[© 2021 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2021 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|