Saudis vowed to stop executing minors; some death sentences remain,

rights groups say

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[January 18, 2021]

By Raya Jalabi [January 18, 2021]

By Raya Jalabi

DUBAI (Reuters) - Five people who committed

crimes in Saudi Arabia as minors have yet to have their death sentences

revoked, according to two rights groups, nine months after the kingdom's

Human Rights Commission (HRC) announced an end to capital punishment for

juvenile offenders.

The state-backed HRC in April cited a March royal decree by King Salman

stipulating that individuals sentenced to death for crimes committed

while minors will no longer face execution and would instead serve

prison terms of up to 10 years in juvenile detention centers.

The statement did not specify a timeline, but in October, in response to

a report by Human Rights Watch (HRW), it said the decree had come into

force immediately upon announcement.

The decree was never carried on state media nor published in the

official gazette as would be normal practice.

In December, state news agency SPA published a list of prominent

"events" of 2020 featuring several royal decrees, but the death penalty

order was not included.

Organisations including anti-death penalty group Reprieve, HRW and the

European-Saudi Organization for Human Rights (ESOHR) as well as a group

of U.S. lawmakers have raised concerns that loopholes in Saudi law could

still allow judges to impose the death sentence on juvenile offenders.

One of the five has appealed and eight face charges that could result in

execution, said the groups, who follow the cases closely.

Reuters established the status of three of the five individuals through

HRC statements but could not independently verify the other two.

The government's Center for International Communications (CIC) dismissed

the concerns, telling Reuters that the royal decree would be applied

retroactively to all cases where an individual was sentenced to death

for offenses committed under the age of 18.

"The Royal Order issued in March 2020 was put into effect immediately

upon its issuance and was circulated to the relevant authorities for

instant implementation," the CIC said in an emailed statement.

ALL EYES ON RIYADH

Saudi Arabia, whose human rights record came under global scrutiny after

the 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi by Saudi agents, is one of

the world's top executioners after Iran and China, rights groups say.

Its de facto leader Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, known

internationally as MbS, enjoyed strong support from U.S. President

Donald Trump.

But President-elect Joe Biden, who takes over in the White House later

this week, has described the kingdom as a "pariah" for its rights record

and said he would take a tougher line.

Six U.S. lawmakers wrote to the Saudi embassy in the United States in

October urging the kingdom to review all ongoing death penalty cases to

identify individuals convicted for crimes committed when they were

children, according to a copy of the letter seen by Reuters.

One of the signatories, Democratic Rep. Tom Malinowski, told Reuters in

December that if the kingdom were to follow through on the execution of

juvenile offenders, "it would make it even harder for Saudi Arabia to

return to the kind of relationships that it wants with the United

States."

He added that Biden would be looking at the kingdom's human rights

policies "very differently to Trump".

Biden officials declined to comment for this article, but referred

Reuters to an earlier statement saying the new administration would

reassess U.S. ties with Saudi Arabia.

DISPUTED FIGURES

Ali al-Nimr and Dawood al-Marhoun were 17 when they were detained in

2012 on charges related to participating in widespread protests in the

Shi'ite-majority Eastern Province. Abdullah al-Zaher was 15 when he was

arrested.

The three, who are among the five juvenile offenders whose death

penalties have yet to be revoked, were sentenced to death by the

Specialized Criminal Court and faced beheading, although the public

prosecutor ordered a review of their sentences in August.

The CIC said the royal decree would be applied to their cases.

[to top of second column]

|

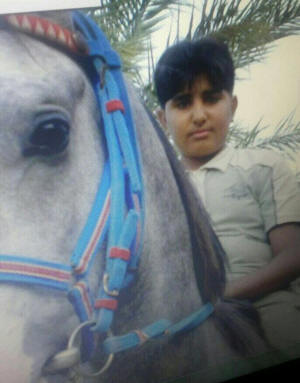

Abdullah al-Zaher is seen in this undated handout photo. Courtesy of

Reprieve/Handout via REUTERS

Their lawyers could not immediately be reached for comment.

In 2018, after assuming his post in a palace coup that ousted the

previous crown prince, MbS pledged to minimise the use of the death

penalty as part of sweeping social reforms.

But in 2019, a record number of about 185 people were executed,

according to the rights groups.

Reuters could not independently confirm the figures. The CIC did not

comment when asked whether this figure was accurate.

In a press release on Monday, the HRC said Saudi Arabia had reduced

the number of executions by 85% in 2020 compared with the previous

year, noting it had documented 27.

TEST CASE?

In an article published last April, state-linked newspaper Okaz

confirmed the existence of the royal decree, but said that the

abolishment only applied to a lesser category of offence under

Islamic law known as "ta'zeer".

These crimes are not clearly defined in the Koran or accompanying

Hadiths and so punishments are left to judges' discretion, and can

amount to death.

Saudi Arabia has no civil penal code that sets out sentencing rules,

and no system of judicial precedent that would make the outcome of

cases more predictable based on past practice.

Judges could still sentence child offenders to death under the other

two categories, according to Saudi Arabia's interpretation of sharia:

"houdoud", or serious crimes which carry a prescribed punishment,

including terrorism, and "qisas", or retribution, usually for

murder, two lawyers and the rights groups said.

Asked why the royal decree was never published and whether it only

applies to the "ta'zeer" category of offense, the CIC declined to

comment.

Some defendants in protest cases have been prosecuted on terror

charges.

In a case watched closely by the rights groups, 18-year-old Mohammad

al-Faraj was facing the death penalty even though he was 15 at the

time of his arrest in 2017 for charges including participating in

protests and attending related funerals, one when he was aged nine.

Ahead of his next hearing scheduled for Jan. 18, a source close to

one of the defendants in Faraj's case said the demand for a "houdoud"

death sentence had recently been withdrawn and prosecutors were

instead seeking the harshest punishment under "ta'zeer".

The CIC said the royal decree would apply retroactively to Faraj's

case, a point the HRC echoed in its press release.

ESOHR expressed concern that without a published decree, the risk of

capital punishment cannot be ruled out.

ESOHR said Faraj was only granted a state-appointed lawyer in

October, was not brought to court and was tortured in detention,

allegations the CIC denied.

Since the start of the pandemic, Faraj has been allowed one weekly

15-minute call to his parents, with in-person visits cancelled, a

source close to the family said.

Reuters was unable to independently confirm the specifics of his

case.

(Reporting by Raya Jalabi; Additional Reporting by Jonathan Landay

in Washington D.C.; Editing by Mike Collett-White)

[© 2021 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2021 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|