East L.A., the cradle of Mexican American culture, seeks greater

independence

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[June 04, 2021]

By Daniel Trotta [June 04, 2021]

By Daniel Trotta

EAST LOS ANGELES, Calif. (Reuters) - East

Los Angeles is home to Mexican American success stories from boxer Oscar

De La Hoya to rock stars Los Lobos to the overachieving calculus

students depicted in the 1988 film "Stand and Deliver."

Yet for all its fame and vibrancy, the almost entirely Latino community

of 120,000 people suffers from an identity crisis, if not a political

one. The 7.4-square-mile (19-square-km) area is not its own city nor

part of the city of Los Angeles but rather an unincorporated area of Los

Angeles County.

Now a group of community leaders hopes to exert more local control by

creating a special district.

As it is, the only elected local government official representing East

L.A. is County Supervisor Hilda Solis, whose district encompasses nearly

2 million people from dozens of cities, unincorporated areas and Los

Angeles neighborhoods.

A special district would give East L.A. its own elected council to set

priorities on solving community problems. Provided East L.A. can

persuade county authorities to cede certain powers, it would also get

more say on how local tax revenue is spent.

"I think of East Los Angeles as the neglected stepchild of Los Angeles.

And that's largely because of its unincorporated status. There's no

local control, and there's no form of community self-determination,"

said Eric Avila, a professor of Chicano studies at UCLA who is

unaffiliated with the special district campaign.

Through the decades, several attempts at becoming a city have failed, so

proponents chose a less ambitious option. A special district still

requires years of planning and, eventually, approval from voters within

the proposed boundaries.

The project is still in its infancy, so no discernable opposition has

coalesced. Solis declined to be interviewed.

"A lot of people from outside of East L.A. are making decisions for us

and that has to stop," said Tony DeMarco, president of the Whittier

Boulevard Merchants Association and a leading advocate for a special

district.

The most recent attempt at cityhood collapsed in 2012 after a body known

as the Local Agency Formation Commission found that as a city East Los

Angeles would have steep budget deficits. Criticism of the study

includes that it took place in the wake of the great recession of

2007-2009, and that new businesses have since arrived.

As a special district, East L.A. would have greater say in determining

enforcement priorities for the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department,

but it would not form its own police department.

For example, supporters of greater home rule want to curtail the havoc

that ensues when "lowriders" - classic cars modified to hang close to

the asphalt and also to rise to improbable heights and angles - cruise

Whittier Boulevard, the main artery through East L.A.

Merchants complain that the cruisers spend little money in town, snarl

traffic, start fights and drink in public.

In large measure, the special district campaign is born out of local

pride.

"If East L.A. had a flag, I'd be flying it," said lifelong resident Alex

Villalobos, 38, a supporter of the special district and the director of

marketing for consulting firm Barrio Planners.

[to top of second column]

|

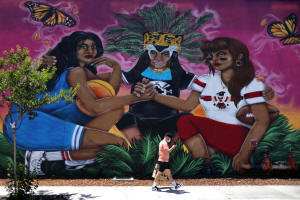

A man walks past a mural, as the coronavirus (COVID-19) disease

continues, in East Los Angeles, California, U.S., May 26, 2021.

REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson

East L.A. has also seen its share of heartbreak.

Journalist and civil rights advocate Ruben Salazar was killed in

East L.A. in 1970, shot in the head with a tear gas projectile by an

L.A. County sheriff's deputy during a Chicano protest over the war

in Vietnam.

The term Chicano, born out of the civil rights era and coinciding

with Cesar Chavez's movement to organize Latino farm workers in the

1960s and '70s, has fallen out of favor.

Whatever the nomenclature, many Mexican Americans of East L.A. have

a complicated identity, much like the community itself.

"We have an American lineage and we have Mexican lineage. We can't

live without one or the other," said Froilan Godiles, an immigrant

who owns a party supplies business in East L.A. "We don't consider

ourselves Latinos. We're Mexican. We're from East L.A. We're North

Americans."

From food to fashion to music to language, Mexican American culture

is proudly on display in an area that was part of Mexico until 1848.

"We like to show off our flavor, our skin. I don't know if it's good

or bad but we like it. We are proud of our roots," Godiles said.

Four major freeways that slice through the community were built in

the 1960s, tearing up neighborhoods, forcing relocations and

lowering property values, making East L.A. more affordable for

working-class immigrants, said Avila, the Chicano studies professor.

That solidified East L.A. as a Mexican American enclave in the

1970s.

Its pull remains strong. Immigrant entrepreneurs say the widespread

use of Spanish and familiarity with Mexican customs make it an ideal

place to start a business. Some shop owners barely speak English,

serving Mexican American customers of multiple generations.

Drivers of the lowriders also are drawn to a place where Mexican

Americans carved out their own, distinct place in Southern

California car culture after World War Two. Today they cruise

beneath East L.A.'s signature landmark, an arch straddling Whittier

Boulevard completed in 1986.

As East L.A. native Ernie Serna, 57, described the allure: "It's

like a Jew going to Jerusalem."

(Reporting by Daniel Trotta; Editing by Donna Bryson and Lisa

Shumaker)

[© 2021 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2021 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |