Painstaking study of 'Little Foot' fossil sheds light on human origins

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[March 03, 2021]

By Will Dunham [March 03, 2021]

By Will Dunham

(Reuters) - Sophisticated scanning

technology is revealing intriguing secrets about Little Foot, the

remarkable fossil of an early human forerunner that inhabited South

Africa 3.67 million years ago during a critical juncture in our

evolutionary history.

Scientists said on Tuesday they examined key parts of the nearly

complete and well-preserved fossil at Britain's national synchrotron

facility, Diamond Light Source. The scanning focused upon Little Foot's

cranial vault - the upper part of her braincase - and her lower jaw, or

mandible.

The researchers gained insight not only into the biology of Little

Foot's species but also into the hardships that this individual, an

adult female, encountered during her life.

Little Foot's species blended ape-like and human-like traits and is

considered a possible direct ancestor of humans. University of the

Witwatersrand paleoanthropologist Ron Clarke, who unearthed the fossil

in the 1990s in the Sterkfontein Caves northwest of Johannesburg and is

a co-author of the new study, has identified the species as

Australopithecus prometheus.

"In the cranial vault, we could identify the vascular canals in the

spongious bone that are probably involved in brain thermoregulation -

how the brain cools down," said University of Cambridge

paleoanthropologist Amélie Beaudet, who led the study published in the

journal e-Life.

"This is very interesting as we did not have much information about that

system," Beaudet added, noting that it likely played a key role in the

threefold brain size increase from Australopithecus to modern humans.

Little Foot's teeth also were revealing.

"The dental tissues are really well preserved. She was relatively old

since her teeth are quite worn," Beaudet said, though Little Foot's

precise age has not yet been determined.

The researchers spotted defects in the tooth enamel indicative of two

childhood bouts of physiological stress such as disease or malnutrition.

[to top of second column]

|

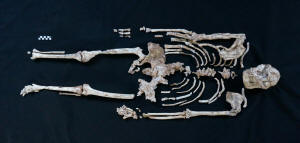

The skeleton of Little Foot is seen in Sterkfontein, South Africa,

in this undated handout photo, obtained by Reuters on March 1, 2021.

RJ Clarke/Handout via REUTERS

"There is still a lot to learn about early hominin biology," said

study co-author Thomas Connolley, principal beamline scientist at

Diamond, using a term encompassing modern humans and certain extinct

members of the human evolutionary lineage. "Synchrotron X-ray

imaging enables examination of fossil specimens in a similar way to

a hospital X-ray CT-scan of a patient, but in much greater detail."

Little Foot, whose moniker reflects the small foot bones that were

among the first elements of the skeleton found, stood roughly

4-foot-3-inches (130 cm) tall. Little Foot has been compared in

importance to the fossil called Lucy that is about 3.2 million years

old and less complete.

Both are species of the genus Australopithecus but possessed

different biological traits, just as modern humans and Neanderthals

are species of the same genus - Homo - but had different

characteristics. Lucy's species is called Australopithecus afarensis.

"Australopithecus could be the direct ancestor of Homo - humans -

and we really need to learn more about the different species of

Australopithecus to be able to decide which one would be the best

candidate to be our direct ancestor," Beaudet said.

Our own species, Homo sapiens, first appeared roughly 300,000 years

ago.

The synchrotron findings build on previous research on Little Foot.

The species was able to walk fully upright, but had traits

suggesting it also still climbed trees, perhaps sleeping there to

avoid large predators. It had gorilla-like facial features and

powerful hands for climbing. Its legs were longer than its arms, as

in modern humans, making this the most-ancient hominin definitively

known to have that trait.

"All previous Australopithecus skeletal remains have been partial

and fragmentary," Clarke said.

(Reporting by Will Dunham in Washington, Editing by Rosalba O'Brien)

[© 2021 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2021 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |