Primordial lightning strikes may have helped life emerge on Earth

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[March 17, 2021]

By Will Dunham [March 17, 2021]

By Will Dunham

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The emergence of the

Earth's first living organisms billions of years ago may have been

facilitated by a bolt out of the blue - or perhaps a quintillion of

them.

Researchers said on Tuesday that lightning strikes during the first

billion years after the planet's formation roughly 4.5 billion years ago

may have freed up phosphorus required for the formation of biomolecules

essential to life.

The study may offer insight into the origins of Earth's earliest

microbial life - and potential extraterrestrial life on similar rocky

planets. Phosphorus is a crucial part of the recipe for life. It makes

up the phosphate backbone of DNA and RNA, hereditary material in living

organisms, and represents an important component of cell membranes.

On early Earth, this chemical element was locked inside insoluble

minerals. Until now, it was widely thought that meteorites that

bombarded early Earth were primarily responsible for the presence of "bioavailable"

phosphorus. Some meteorites contain the phosphorus mineral called

schreibersite, which is soluble in water, where life is thought to have

formed.

When a bolt of lightning strikes the ground, it can create glassy rocks

called fulgurites by super-heating and sometimes vaporizing surface

rock, freeing phosphorus locked inside. As a result, these fulgurites

can contain schreibersite.

The researchers estimated the number of lightning strikes spanning

between 4.5 billion and 3.5 billion years ago based on atmospheric

composition at the time and calculated how much schreibersite could

result. The upper range was about a quintillion lightning strikes and

the formation of upwards of 1 billion fulgurites annually.

Phosphorus minerals arising from lightning strikes eventually exceeded

the amount from meteorites by about 3.5 billion years ago, roughly the

age of the earliest-known fossils widely accepted to be those of

microbes, they found.

"Lightning strikes, therefore, may have been a significant part of the

emergence of life on Earth," said Benjamin Hess, a Yale University

graduate student in earth and planetary sciences and lead author of the

study published in the journal Nature Communications.

[to top of second column]

|

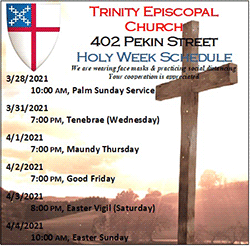

Mass lightning bolts light up night skies by Daggett airport from

monsoon storms passing over the high deserts, north of Barstow,

California, July 1, 2015. Picture taken using long exposure.

REUTERS/Gene Blevins/File Photo

"Unlike meteorite impacts which decrease exponentially through time,

lightning strikes can occur at a sustained rate over a planet's

history. This means that lightning strikes also may be a very

important mechanism for providing the phosphorus needed for the

emergence of life on other Earth-like planets after meteorite

impacts have become rare," Hess added.

The researchers examined an unusually large and pristine fulgurite

sample formed when lightning struck the backyard of a home in Glen

Ellyn, Illinois, outside Chicago. This sample illustrated that

fulgurites harbor significant amounts of schreibersite.

"Our research shows that the production of bioavailable phosphorus

by lightning strikes may have been underestimated and that this

mechanism provides an ongoing supply of material capable of

supplying phosphorous in a form appropriate for the initiation of

life," said study co-author Jason Harvey, a University of Leeds

associate professor of geochemistry.

Among the ingredients considered necessary for life are water,

carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur and phosphorus, along

with an energy source.

Scientists believe the earliest bacteria-like organisms arose in

Earth's primordial waters, but there is a debate over when this

occurred and whether it unfolded in warm and shallow waters or in

deeper waters at hydrothermal vents.

"This model," Hess said, referring to phosphorous unlocked by

lightning, "is applicable to only the terrestrial formation of life

such as in shallow waters. Phosphorus added to the ocean from

lightning strikes would probably be negligible given its size."

(Reporting by Will Dunham, Editing by Rosalba O'Brien)

[© 2021 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2021 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |