Mars long ago was wet. You may be surprised where the water went

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[March 18, 2021]

By Will Dunham [March 18, 2021]

By Will Dunham

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Mars was once a wet

world, with abundant bodies of water on its surface. But this changed

dramatically billions of years ago, leaving behind the desolate

landscape known today. So what happened to the water? Scientists have a

new hypothesis.

Researchers said this week that somewhere between about 30% and 99% of

it may now be trapped within minerals in the Martian crust, running

counter to the long-held notion that it simply was lost into space by

escaping through the upper atmosphere.

"We find the majority of Mars' water was lost to the crust. The water

was lost by 3 billion years ago, meaning Mars has been the dry planet it

is today for the past 3 billion years," said California Institute of

Technology PhD candidate Eva Scheller, lead author of the NASA-funded

study published on Tuesday in the journal Science.

Early in its history, Mars may have possessed liquid water on its

surface approximately equivalent in volume to half of the Atlantic

Ocean, enough to have covered the entire planet with water perhaps up to

nearly a mile (1.5 km) deep.

Water is made up of one oxygen and two hydrogen atoms. The amount of a

hydrogen isotope, or variant, called deuterium present on Mars provided

some clues about the water loss. Unlike most hydrogen atoms that have

just a single proton within the atomic nucleus, deuterium - or "heavy"

hydrogen - boasts a proton and a neutron.

[to top of second column]

|

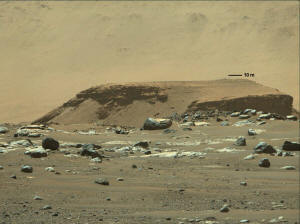

A tall outcropping of rock, with layered deposits of sediments in

the distance, marking a remnant of an ancient, long-vanished river

delta in Jezero Crater, are pictured in this undated image taken by

NASA's Mars rover Perseverance from its landing site, and supplied

to Reuters on March 5, 2021. NASA/JPL-Caltech/Handout via REUTERS

Ordinary hydrogen can escape through the atmosphere into space more

readily than deuterium. Water loss through the atmosphere, according

to scientists, would leave behind a very large ratio of deuterium

compared to ordinary hydrogen. The researchers used a model that

simulated the hydrogen isotope composition and water volume of Mars.

"There are three key processes within this model: water input from

volcanism, water loss to space and water loss to the crust. Through

this model and matching it to our hydrogen isotope data set, we can

calculate how much water was lost to space and to crust," Scheller

said.

The researchers suggested that a lot of the water did not actually

leave the planet, but rather ended up trapped in various minerals

that contain water as part of their mineral structure - clays and

sulfates in particular.

This trapped water, while apparently plentiful when taken as a

whole, may not provide a practical resource for future astronaut

missions to Mars.

"The amount of water within a rock or mineral is very small. You

would have to heat a lot of rock to release water in an appreciable

amount," Scheller said.

(Reporting by Will Dunham, Editing by Rosalba O'Brien)

[© 2021 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2021 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |