Analysis: U.S. Fed's Powell faces political test on bank capital relief

question

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[March 18, 2021]

By Pete Schroeder [March 18, 2021]

By Pete Schroeder

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - An esoteric bank capital rule has become an

unlikely political hot potato for U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome

Powell, as the Republican appointee enters the final 12 months of his

term under the administration of Democratic President Joe Biden,

analysts said.

On March 31, an emergency pandemic regulatory relief measure that for

the past year has allowed Wall Street banks to hold less capital against

certain assets as a cushion against potential losses is due to expire.

The industry has been lobbying the Fed to extend the relief, arguing the

rule is fundamentally flawed and reprising it could stall the U.S.

economic recovery. But powerful Democrats, already angry with Powell for

granting Wall Street several regulatory breaks under the Trump

administration, are pressuring him to deny another industry giveaway.

Whether to extend the relief has become the first major political test

for Powell under the Biden administration as, like his predecessors, he

is expected to seek re-nomination.

Appearing to yield to the industry could put a second term in jeopardy

for Powell, who was appointed Fed chair by former Republican President

Donald Trump, because anti-Wall Street progressives control the Senate

Banking Committee, which vets Fed nominees, and hold sway over White

House financial nominees, analysts said.

"Powell [is] in a politically precarious position," said Isaac Boltansky,

director of policy research at Washington-based Compass Point Research &

Trading. "This decision will leave someone politically important unhappy

with him."

The Fed, an independent agency, declined to comment. When asked about

the rule at a Wednesday press briefing, Powell said the central bank

would announce "something" in coming days.

Regulators introduced the supplementary leverage ratio following the

decade-ago financial crisis as an extra safeguard. It requires big banks

to hold an additional layer of capital against assets, regardless of

their risk.

In April 2020, after a meltdown in the Treasury market and as

cash-strapped bank customers rushed to draw down credit lines, the Fed

temporarily exempted banks' holdings of U.S. Treasuries and deposits

held with the central bank from the rule.

Wall Street lobby groups say if the Fed doesn't extend the relief, banks

may have to be pickier about accepting deposits, pull back from lending,

or buy less Treasury debt. That could spark another bout of Treasury

market turmoil and reduce overall credit in the system, setting back the

recovery.

The Bank Policy Institute, which represents JPMorgan Chase & Co and

Goldman Sachs Group Inc, among others, said this month that returning to

the normal rules could create "an incentive for banks to reduce

low-risk, balance-sheet-intensive activities." It said the Fed should

extend the relief indefinitely and pursue a broader overhaul of its

rules.

Progressives, including Senators Elizabeth Warren and Sherrod Brown, who

now heads the Senate Banking Committee, say banks are cynically seizing

an opportunity to ease more rules.

[to top of second column]

|

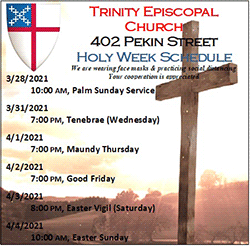

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell testifies before the Senate

Banking Committee hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, U.S.,

December 1, 2020. Susan Walsh/Pool via REUTERS

They point out that big banks have enough capital to buy back shares

and issue dividends - activities that the Fed must approve based on

banks' capital reserves - and they have warned Powell in published

letters not to "weaken one of the most important post-crisis

regulatory reforms."

MAYHEM FEAR

Some analysts agree banks are overplaying the risks.

Credit Suisse analyst Zoltan Pozsar wrote on Tuesday that the

overwhelming majority of the exempt assets are held by banks'

operating subsidiaries, not by the bank holding companies, to which

the Fed granted the relief.

And while regulators granted similar optional relief to those

subsidiaries, most failed to make use of it because there were

strings attached. That means any expiration could have a muted

impact, wrote Pozsar. "Neither the Fed nor the market should fear

mayhem if the exemption expires," he wrote.

Under Powell's leadership, the Fed has revised and eliminated bank

rules arguing they were overly burdensome. The changes drew the ire

of progressive Democrats and advocacy groups, who say they increase

risks and hurt consumers.

Powell - who was originally appointed to the Fed's Board of

Governors as a moderate Republican by Democratic President Barack

Obama in 2012 and would serve out the rest of his term until 2028 if

he is not renamed to a second term as Fed chair - has won bipartisan

support for his swift handling of the economic crisis. But siding

with Wall Street would hand ammunition to progressives who want a

Democrat in a position with such singular power to steer the U.S.

economy, especially if Powell fails to persuade the board's

longstanding Democratic governor Lael Brainard to back the move.

She voted for the relief in April, but has dissented against several

rule changes she said were too generous to Wall Street, and her

votes are closely tracked by progressives.

The Fed may in theory be independent, but it is acutely aware of the

dynamics, said Ed Mills, a policy analyst with Raymond James.

"Does the Fed want one of their first policy decisions of Senator

Brown’s chairmanship to be one that Brown considers a 'grave

error'?" he said.

(Reporting by Pete Schroeder; additional reporting by Howard

Schneider; editing by Michelle Price and Leslie Adler)

[© 2021 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2021 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |