Special Report: Pompeo rejected U.S. effort to declare 'genocide' in

Myanmar on eve of coup, officials say

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[March 25, 2021]

By Simon Lewis and Humeyra Pamuk [March 25, 2021]

By Simon Lewis and Humeyra Pamuk

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - In the last days of

the Trump administration, some U.S. officials urged outgoing Secretary

of State Mike Pompeo to formally declare that the Myanmar military’s

campaign against the Rohingya minority was a genocide.

Such a determination, a culmination of years of State Department

investigation and legal analysis, would send a signal that the generals

would not enjoy impunity for their persecution of the Muslim group since

2017, the officials hoped.

Pompeo never made that call. Less than two weeks after he left office on

Jan. 20, Myanmar’s generals seized power in a coup.

The 11th-hour scramble inside the State Department underscores how the

United States struggled to formulate consistent policy toward Myanmar

after the military began opening the country a decade ago.

Officials say Washington’s ability to influence events in Myanmar is

limited, and U.S. policy was not the only factor that influenced the

military’s decision to seize back power.

But the failure to condemn the slaughter of the Rohingya in the

strongest terms available was a missed opportunity to have “a

moderating” effect on the generals, said Morse Tan, who backed a

genocide determination on Myanmar as head of the Office of Global

Criminal Justice at the State Department.

“Maybe (the coup) would have happened anyways, but I think it would have

at least been a significant weight in the direction towards prevention

and deterrence,” Tan said.

Pompeo, as secretary of state, had the sole authority to make a genocide

determination. Tan said Pompeo never explained why he declined to do so.

Spokespeople for Pompeo did not reply to repeated emails seeking comment

for this story, and they did not make him available for an interview.

Reuters calls to a Myanmar military spokesman were not answered. The

army has said it was conducting counter-terrorism operations. Civilian

leader Aung San Suu Kyi, now detained by the military, previously denied

that the acts constituted genocide.

Reuters spoke to 18 current and former U.S. officials who worked on

U.S.-Myanmar policy. The interviews showed how officials across two

administrations argued over how to balance accountability for Myanmar’s

military - internationally condemned for its abuses against civilians -

and the need for continued engagement with a country that had made

nascent steps toward democracy.

U.S. officials often disagreed on whether a tough response might

backfire and end up weakening the hand of Myanmar’s civilian government

without improving conditions for the Rohingya.

That debate came to a head during a State Department examination of the

military’s bloody 2017 campaign that pushed at least 730,000 members of

Myanmar’s Rohingya minority into neighboring Bangladesh.

The State Department in 2018 conducted a months-long examination

process, officials said. It hired outside lawyers, the people said, to

gather evidence of the army’s atrocities and to analyze whether those

actions constituted “crimes against humanity” or “genocide” - offenses

that ultimately could be charged in international courts.

At the time, the United States had referred to events in Myanmar as

“ethnic cleansing,” a descriptive term that cannot be used to prosecute

perpetrators. A U.S. determination of genocide, in particular, carries a

lot of weight, according to officials and rights advocates who hoped

such a call would rally global support to hold the generals accountable.

The United Nations defines genocide as acts such as pogroms and forced

sterilizations intended to destroy a national, ethnical, racial or

religious group.

Calling the events genocide would be a major boost for hundreds of

thousands of survivors living in refugee camps, said Wai Wai Nu, a

Rohingya former political prisoner and activist. “They will feel like

their suffering, the crimes that happened against them, have been

recognized,” she said.

Officials told Reuters that the process, after months of work, ended

abruptly in August 2018 because Pompeo became enraged after details of

the deliberations leaked.

These people said policy toward Myanmar was often overshadowed by the

Trump administration’s top foreign policy priority: China. Some State

Department officials argued that punishing Myanmar for the army’s

atrocities would push the country into China’s orbit.

In 2020, as ties between the United States and China became increasingly

adversarial, Pompeo tasked the department to make an atrocity

determination for Beijing’s persecution of Uighurs and other Muslims in

its western Xinjiang province. United Nations experts say a million

Muslims are detained in camps and are subjected to numerous abuses,

including forced sterilizations, which China has denied.

In a previously unreported effort, some State Department officials said

they encouraged Pompeo to take a fresh look at Myanmar in a parallel

process in mid-2020. They argued that atrocities there were

well-documented and had been going on for years. If the State Department

leveled a genocide determination against China, a geopolitical rival,

but failed to do so with Myanmar, officials said the administration

could face criticism about its determination being politically

motivated.

Ultimately, Pompeo declared a genocide was taking place in China. But he

made no atrocity determination for Myanmar, despite new evidence that

State Department lawyers said justified the genocide label there,

several former U.S. officials familiar with the process, including

Trump-era appointees, told Reuters.

Aides who worked with Pompeo at the State Department said he would have

weighed a broad range of factors in making his decision.

SEEKING ACCOUNTABILITY

Inside the State Department, officials were split on the genocide label

for Myanmar, Reuters has learned. The regional bureau for Asia did not

support a genocide determination, in part because some bureau officials

felt Myanmar was on a trajectory toward democracy, in contrast to China,

where repression was ramping up, former officials said. They believed a

genocide call would not help Suu Kyi’s civilian government in its

struggle with the military, the officials said.

The head of the East Asian and Pacific Affairs bureau at the time, David

Stilwell, a Trump appointee, declined to confirm or deny the difference

of opinion within the State Department. “These are complex issues that

we wrestled with for months,” he said.

Tan, the head of the Office of Global Criminal Justice, defended the

Trump administration’s overall handling of Myanmar despite its failure

to call out genocide there. He said State Department officials under

Pompeo worked hard to respond to the atrocities against the Rohingya,

including providing financial aid to refugees and supporting a case

against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice, brought by The

Gambia.

Washington in December 2019 slapped Myanmar’s Commander in Chief Min

Aung Hlaing with sanctions freezing any U.S. assets he may have and

forbidding Americans to do any business with him. Human-rights groups

say his family businesses remain largely unscathed. On Feb. 1, Min Aung

Hlaing led the junta that overthrew Myanmar’s civilian government and

detained State Counselor Suu Kyi, the Nobel Peace Prize winner who leads

the National League for Democracy (NLD) party that won elections in

November.

Reuters calls to a military spokesman seeking comment from Min Aung

Hlaing were not answered. Reuters was unable to reach Suu Kyi for

comment.

Dr. Sasa, a special envoy for lawmakers mainly from the NLD who oppose

the coup, promised the group will seek "justice" for the Rohingya. It is

unclear if his views represent Suu Kyi or her party's leadership, who

are being held incommunicado by the ruling junta.

Sasa told Reuters a genocide determination by the United States would

"have a huge impact" on the military.

"What we desperately need is the strong, unifying message from

Washington and (the) international community that these military

generals will no longer get away free" with crimes including "genocide,"

Sasa said in an email.

The coup presented newly inaugurated U.S. President Joe Biden with his

first international crisis and a test of his pledge to stand up for

human rights and democracy. His foreign policy team quickly imposed

stronger sanctions against the generals and some of their children and

companies they control, and tried to organize an international response

to pressure them into reversing course.

This has not deterred the junta, which has now killed at least 275

people and arrested or charged more than 2,900 political leaders and

others who have taken to the streets in massive numbers to oppose the

coup.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Pompeo’s successor, said in January

he would review whether Myanmar committed genocide against the Rohingya.

In an emailed statement, the State Department said it is urging

Myanmar’s military to restore the country’s democratically elected

government, end the violence and release people who have been unjustly

detained. “We will ensure achieving accountability for the atrocities

against Rohingya is pivotal to our human rights-centered policy,” the

State Department said.

[to top of second column]

|

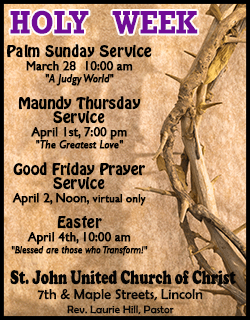

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo speaks at the National Press Club in

Washington, DC, U.S., January 12, 2021. Andrew Harnik/Pool via

REUTERS/

WHAT MAKES A GENOCIDE?

Genocide, considered the most serious international offense, was

first used to describe the Nazi Holocaust. It was established as a

crime under international law in a 1948 United Nations convention.

Since the end of the Cold War, the State Department has formally

used the term six times to describe massacres in Bosnia, Rwanda,

Iraq and Darfur, the Islamic State’s attacks on Yazidis and other

minorities, and most recently this year, over China’s treatment of

Uighurs and other Muslims. China denies the genocide claims.

Individual U.S. officials and other branches of government have also

used the term. In 2019, for example, Congress recognized as genocide

the mass killings and deportations of Armenian subjects of the

Ottoman Empire during World War I. Turkey denies it was a genocide.

At the State Department, such a determination normally follows a

meticulous internal process. Still, the final decision is up to the

secretary of state, who weighs whether the move would advance

American interests, officials said.

A determination of genocide does not automatically unleash punitive

U.S. action. But human-rights advocates say it can help mobilize an

international response to prevent further atrocities. For instance,

former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell’s recognition of

genocide in Darfur in 2004 helped isolate and stigmatize

then-Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir and bring about his 2009

indictment in the International Criminal Court, the United States

Holocaust Memorial Museum said in a report.

February’s coup was the latest chapter in deteriorating U.S.-Myanmar

relations, and a major turnaround from the high hopes that prevailed

a decade ago.

In 2010, after a half-century of military rule, many of Myanmar’s

roughly 54 million people saw life improve after the military

initiated a transition towards democracy. The generals released Suu

Kyi from house arrest and allowed her to run for office. The

military opened energy and telecoms tenders to foreign companies.

The United States responded by lifting a trade embargo and easing

some sanctions, including those on Burmese banks. In 2016, U.S.

President Barack Obama welcomed Suu Kyi to Washington and lifted

most remaining sanctions on Myanmar.

Some U.S. officials thought the move premature, including Tom

Malinowski, a congressman who served as assistant secretary of state

for democracy, human rights and labor at the time. “We needed to

maintain pressure and leverage on the military and military-owned

companies in Burma until more progress was made,” he told Reuters in

an interview.

Warning signs proliferated throughout Obama’s tenure. Myanmar’s

generals resisted calls to reform the country’s constitution, which

locked in the military’s political power. Fighting between the army

and armed groups seeking ethnic autonomy intensified in some parts

of the country.

Most stark was the situation for the Rohingya, a long-suffering

Muslim minority numbering more than 1 million in the western state

of Rakhine. The Rohingya had faced earlier waves of violence from

security forces and from their Buddhist neighbors. Rohingya are

largely denied citizenship under a 1982 law that favors certain

ethnic groups, and in 2015 were stripped of identity papers that had

previously allowed them to vote.

By August 2018, reporters and human rights groups had documented

killings, mass rape and the burning of Rohingya villages during a

2017 military operation. Medical nonprofit Doctors Without Borders

said at least 9,400 people were killed. A U.N. fact-finding mission

said that estimate was conservative.

The military has said it was fighting Rohingya terrorists and that

its troops followed strict rules of engagement.

Suu Kyi traveled to the International Court of Justice at The Hague

in 2019 to defend the country against The Gambia’s accusation of

genocide, a move that tarnished her reputation overseas.

She told the court that Myanmar made efforts to investigate the

violence, proof there was no genocidal intent. "The situation in

Rakhine is complex and not easy to fathom,” she said.

U.S. diplomats working for the Trump administration avoided

criticizing Suu Kyi, believing she still represented the best hope

for Myanmar’s democracy, officials said.

In the summer of 2018, the United States was preparing to levy

sanctions on some of Myanmar’s generals as the State Department was

planning the rollout of a report it commissioned documenting

eye-witness accounts from Rohingya survivors of the brutality, a

half-dozen people involved in the process told Reuters.

Pompeo, meanwhile, was presented with options on an atrocity

determination, the people said. But the State Department was split

on the issue.

The Office of the Legal Advisor – the legal team which weighs in on

such matters - concluded that crimes against humanity was a legally

sound determination; it had not reached a conclusion regarding

genocide, the people said. Officials in other parts of the State

Department told Reuters they believed the genocide label was

warranted by the Department’s own research, including interviews

with hundreds of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh who said they had

witnessed killings by the military.

Officials said the process came to a halt on Aug. 13 in 2018 when

the news outlet Politico published a story it said was based on

leaked excerpts of a draft statement, shedding light on Pompeo’s

deliberations.

Pompeo considered the leak an attempt to pressure him into deeming

the Myanmar atrocities a genocide, former officials said. During

Pompeo’s nearly three-year tenure at the State Department, critics

said, he questioned the loyalty of career diplomats and their will

to enforce Trump’s agenda.

"To say he was infuriated is an understatement," a former U.S.

official directly involved in the process said.

As a result, the process was derailed, officials said, and Pompeo

walked away without making any determination. The State Department

on Sept. 24, 2018 published its report on the Myanmar atrocities in

a hard-to-find part of its website with no press release,

announcement or other publicity, officials said.

“We were all in shock and disappointed,” said one lawyer who worked

on the report.

Sam Brownback, Trump’s envoy on religious freedom at the State

Department, said there was clear evidence that the Rohingya had been

suffering genocide “for decades.”

“That part is not in question,” Brownback said. “It's getting the

determination that was difficult."

Still, he praised Pompeo and declined to discuss internal

deliberations as to why no genocide determination was reached.

OVERSHADOWED BY CHINA

By 2020, countering China had become the top U.S. foreign policy

priority as ties between the world’s top two economies frayed.

Washington grew vocal about China's repression of Uighurs and other

Muslims. China has been accused of detaining more than 1 million

Uighurs and other minorities and subjecting them to forced labor and

coercive family planning, including sterilization.

China denies abuses and says its camps provide vocational training

and are needed to fight extremism.

As Pompeo aides in mid-2020 moved to prepare a determination on what

was happening in Xinjiang, some department officials told him they

should also revisit the Myanmar evidence.

“Failure to address the mass atrocities against the Rohingya and

call them by their right name would cast a cloud over any subsequent

determination on Xinjiang,” said Kelley Currie, then the State

Department’s ambassador on global women’s issues who was deeply

involved in the Myanmar effort.

Other State Department bureaus responsible for promoting human

rights, religious freedoms and global criminal justice likewise lent

their support to a genocide determination, U.S. officials said.

Their views were by that time supported by the Office of the Legal

Adviser, which in late 2020 reached a new verdict that supported a

genocide determination against Myanmar, four former U.S. officials

familiar with the matter said. The legal case had been bolstered by

the testimony of two Myanmar army defectors, now in the custody of

the ICC at The Hague, who said they were given orders to massacre

Rohingya.

But there was “vigorous opposition” to the genocide label from

officials in the State Department’s East Asian and Pacific Affairs

bureaus, which favored continued engagement with Myanmar, according

to Currie, the former ambassador on women’s issues.

“They opposed it on two grounds: that it would cause the military to

launch a coup, and that it would push Burma closer to China,” she

said.

On Jan. 19, his last full day in office, Pompeo declared that China

had committed genocide and crimes against humanity in Xinjiang. That

determination came despite the objections of some State Department

lawyers that the criteria for genocide were not met, four officials

told Reuters.

On Myanmar, there was silence. Officials said they never heard back

from Pompeo.

(Reporting by Simon Lewis and Humeyra Pamuk; editing by Mary

Milliken and Marla Dickerson)

[© 2021 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2021 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |