'Turkey First:' Erdogan's power push poses challenge for Biden

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[March 25, 2021]

By Orhan Coskun and Humeyra Pamuk [March 25, 2021]

By Orhan Coskun and Humeyra Pamuk

ANKARA (Reuters) - When Turkish President

Tayyip Erdogan last received Joe Biden on official business, in August

2016, Erdogan had just sent tanks into Syria.

Seated by Erdogan's side on a cream-and-gold-leaf chair in Ankara's

presidential palace, then-Vice President Biden said, "We're supportive

of the operation."

U.S. air support helped that incursion, as Washington put on a show of

solidarity after a coup attempt against Erdogan the previous month;

Biden visited parliament to see the bomb damage inflicted when rogue

troops in tanks and fighter jets had tried to seize power.

Nearly five years on, Biden is president and Erdogan's interventions

abroad have multiplied, to the point where Turkey has a stake in many of

the struggles that Biden must contend with in the world's most volatile

region. Interviews with a dozen insiders and officials from both

countries show how the weeks around the coup and Biden's visit set the

stage for a new era of Turkish power projection, starting with that

incursion into Syria.

Turkey has muscled its way to prominence in the Middle East, North

Africa and the Caucasus. At home, Erdogan launched a purge which would

eventually remove 20,000 military personnel, and started to concentrate

authority around the presidency.

Leaning heavily on a close personal relationship with Biden's

predecessor Donald Trump - advisers said Erdogan used to call Trump on

the golf course - Erdogan developed a vision of what one Western

diplomat called "a club of strong leaders who sort out the world."

That was a vision Erdogan shared with Trump, but not with Biden, who has

publicly described Erdogan as an autocrat, and promised U.S. diplomats

in February the United States would address a "new moment of advancing

authoritarianism" in the world through old-fashioned diplomacy and

alliance-building.

It will not be easy. Since 2016, the Turkish leader has waged three more

incursions in Syria, one directly targeting Kurdish fighters allied with

the United States. He has changed the course of Libya's civil war,

bought weapons from Russia, challenged the maritime claims of European

neighbours in the east Mediterranean, and backed Azerbaijan's military

victory over Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh.

At the weekend, Erdogan abruptly pulled Turkey out of a convention

protecting women from violence, a move that his U.S. and EU allies said

marked another backward step for human rights in Turkey. He also plunged

markets into turmoil by sacking a central bank governor admired by

Western investors.

Still, Turkey hopes a European Union summit this week can be a step to

improving strained ties, the government says. Erdogan has also said he

will seek good relations with Biden, but he insists Turkey needs to

protect its interests.

"We have no eyes on any country's land, sea or sovereignty," Erdogan

told officers at the end of a major Mediterranean naval exercise this

month. "We are just trying to protect our homeland and our rights."

Asked if U.S. support for Turkey's earliest Syria incursion may have

encouraged Ankara in its military operations, the State Department

declined to comment.

"The U.S. is trying to patch together the very status quo Erdogan

rejects," said Max Hoffman, associate director at the Center for

American Progress, a Washington think tank which has helped shape

policies of Biden's Democrat Party. "There is obvious tension."

THE 'A-TEAM'

When Biden visited Turkey in 2016, the country was in shock from the

failed coup. But Erdogan, who had long chafed against a powerful

military that resisted his calls for intervention in Syria, saw

opportunity in the turmoil. He described the coup attempt as a "gift

from God" and an opportunity to cleanse the army.

Two Turkish officials close to him say two incidents four years apart

show how power shifted to the president. When a Turkish reconnaissance

plane was shot down by Syria in 2012, Erdogan wanted to send five

Turkish jets to strike Syrian targets in retaliation, but was overruled

by officers who said that would risk an escalation the army was not

ready for.

Turkey's defence ministry declined to comment on that account.

A month after the 2016 coup attempt, when an Islamic State suicide

bomber hit a wedding in southern Turkey, Erdogan was determined to

strike the Islamist group in its Syrian haven. This time, and with U.S.

help, he succeeded.

Ahmet Davutoglu and Ali Babacan, who served as senior ministers in

Erdogan governments before breaking away to set up rival political

parties, told Reuters that starting in 2016 the president sidelined the

foreign ministry as well as the military general staff.

Babacan, a former economy and foreign minister, said Turkey had

previously avoided direct military interventions. Davutoglu, who served

as prime minister and championed a policy of "zero problems with

neighbours," said that before 2016, "opinions would be sought ... We

would then reach a final view and convey it to the prime minister or

president."

Those former allies said the change to a narrow circle of advisers

accelerated Turkey's more hawkish stance.

Officially, security and military decisions are taken by the cabinet and

National Security Council, but three political and security officials,

as well as diplomats and analysts, say Erdogan relies mainly on Hulusi

Akar - a military commander held hostage in the 2016 coup who is now

defence minister - as well as intelligence chief Hakan Fidan and

presidential spokesman and adviser Ibrahim Kalin.

"These people, who almost always come together for foreign operations,

work as Erdogan's A-Team," said a security official who works with the

presidency.

Officials from the presidency, intelligence organisation and defence

ministry declined to comment on the roles played by Akar, Fidan and

Kalin, or the statements by the former ministers.

[to top of second column]

|

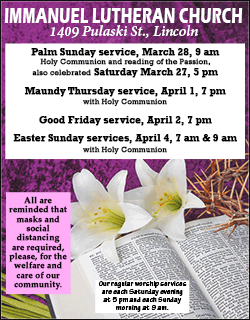

Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan (R) and U.S. Vice President Joe

Biden chat after their meeting in Istanbul, Turkey January 23, 2016.

REUTERS/Sedat Suna/Pool

FRENEMIES

A Turkish aide summed up Erdogan's mindset as "Turkey first."

Ankara, the aide said, was tired of scenarios where the United

States or Russia "sets the rules, while Turkey pays the price."

The 2016 operation in Syria, for example, curbed the gains of

Kurdish fighters the United States had picked as partners against

Islamic State. Erdogan went on to play dual roles with Moscow and

Washington.

In Libya, Turkey sent armed drones, military trainers and Syrian

mercenaries to drive back an assault on Tripoli that had been backed

by Russia. His move against Moscow came months after Turkey bought

$2.5 billion of Russian missile defence systems - a deal which in

turn angered Washington and led to U.S. sanctions on Turkey's

defence industry.

"It was very evident that they were trying to exert more influence

in the Middle East region and some of the Gulf states as well,"

General Joseph Votel, the commander of U.S. troops in the Middle

East at the time, told Reuters.

Erdogan has also challenged the European Union, sending ships to

explore for natural gas in waters long claimed by Greece and Cyprus.

When the EU threatened sanctions, Erdogan ignored the threats.

Beyond the immediate neighbourhood, Erdogan set up military bases in

Qatar and Somalia, projecting Turkish force into the Gulf and Horn

of Africa.

"As these operations were undertaken, Turkey realized its own

capabilities, and realized that its competitors were unable – or

unwilling – to react," said Ozgur Unluhisarcikli, Turkey director of

the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

"Turkey basically had a free hand ... and realized it could change

the reality on the ground."

GAME-CHANGER

Erdogan also found home-grown military solutions. His son-in-law

Selcuk Bayraktar co-owns Baykar, a company that pioneered Turkey's

domestic drone production. Its aircraft have helped the army strike

distant opponents without risking military lives in combat, and are

part of Ankara's self-declared drive to develop an independent arms

industry.

Turkey says it has used drones against Kurdish militants in

southeast Turkey and northern Iraq, where deploying ground troops is

hazardous. In Libya, its drones destroyed Russian air defence

systems. In a campaign against Russian-backed Syrian government

forces in Idlib in northern Syria in early 2020, drones helped

strike three Syrian fighter jets, eight helicopters and 151 tanks,

according to the Turkish military.

The scale and impact of the operations has grabbed attention.

"Even if only half those claims are true, the implications are

game-changing," said Britain's Defence Minister Ben Wallace in a

speech about the future of air power in conflict. Turkey has

deployed electronic warfare, lightly armed drones and smart

ammunition "to stop tanks, armoured cars and air defence systems in

their tracks."

Beyond the battlefield, Erdogan's highly personalised diplomacy has

changed the course of events. He spoke regularly to Trump, in calls

that U.S. advisers said often veered off the scripts U.S.

administration officials prepared.

Erdogan intensified that connection in March 2018 after Trump fired

his secretary of state and national security adviser, who had been

working to defuse a dispute with Turkey over Syria. The sacking led

Erdogan to behave as if contact with anyone other than the president

was a waste of time, said Fiona Hill, who served as senior director

for European and Russian Affairs on Trump's National Security

Council.

On a call in December 2018, Trump was briefed to warn Erdogan

against an operation in northeast Syria where the Turkish leader

planned to target the U.S.-allied Kurds, according to U.S.

officials. Instead, encouraged by Erdogan, Trump promised to

withdraw U.S. troops from Syria and hand responsibility for fighting

Islamic State in Syria to Turkey.

That decision, later partly reversed, surprised even Erdogan's

officials, they told Reuters.

BIDEN SILENT

Erdogan has since resumed talks with Greece over their maritime

dispute, toned down a war of words with France's president and

played up prospects of mending ties with Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

But his incursions have earned him enemies, and as his inner circle

has narrowed at home, polls have shown falling support for his

party, which relied on an alliance with a smaller nationalist party

for a majority in the 2018 parliamentary vote.

A compilation of 15 recent polls in February showed their support at

46%, suggesting he faces a battle to extend his power into a third

decade in elections due by 2023.

More immediately, he faces a new administration in the White House.

Last week, Erdogan chided Biden for saying in a U.S. television

interview he thought Putin was a killer, describing the comments as

unacceptable and unfitting for a U.S. President.

Two months after taking office, Biden has yet to call the Turkish

president.

(Orhan Coskun reported from Ankara, Humeya Pamuk from Washington,

D.C.; Writing by Dominic Evans; Edited by Sara Ledwith)

[© 2021 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2021 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |