Breakthrough infections can lead to long COVID; genes may explain

critical illness in young, healthy adults

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[October 28, 2021]

By Nancy Lapid [October 28, 2021]

By Nancy Lapid

(Reuters) - The following is a summary of

some recent studies on COVID-19. They include research that warrants

further study to corroborate the findings and that have yet to be

certified by peer review.

Breakthrough infections can lead to long COVID

The persistent syndrome of COVID-19 after-effects known as long COVID

can develop after "breakthrough" infections in vaccinated people, a new

study shows. Researchers at Oxford University in the UK reviewed data on

nearly 20,000 U.S. COVID-19 patients, half of whom had been vaccinated.

Compared to unvaccinated patients, people who were fully vaccinated -

and in particular those under age 60 - did have lower risks for death

and serious complications such as lung failure, need for mechanical

ventilation, ICU admission, life-threatening blood clots, seizures, and

psychosis. "On the other hand," the research team reported on medRxiv on

Tuesday ahead of peer review, "previous vaccination does not

appear to protect against several previously documented outcomes of

COVID-19 such as long COVID features, arrhythmia, joint pain, Type 2

diabetes, liver disease, sleep disorders, and mood and anxiety

disorders." The absence of protection from long COVID "is concerning

given the high incidence and burden" of these lasting problems, they

added.

Genes may explain critical COVID-19 in young, healthy adults

A gene that helps the coronavirus reproduce itself might contribute to

life-threatening COVID-19 in young, otherwise healthy people, new

findings suggest. French researchers studied 72 hospitalized COVID-19

patients under age 50, including 47 who were critically ill and 25 with

non-critical illness, plus 22 healthy volunteers. None of the patients

had any of the chronic conditions known to increase the risk for poor

outcomes, such as heart disease or diabetes. Genetic analysis identified

five genes that were significantly "upregulated," or more active, in the

patients with critical illness, of which the most frequent was a gene

called ADAM9. As reported on Tuesday in Science Translational Medicine,

the researchers saw the same genetic pattern in a separate group of 154

COVID-19 patients, including 81 who were critically ill. Later, in lab

experiments using human lung cells infected with the coronavirus, they

found that blocking the activity of the ADAM9 gene made it harder for

the virus to make copies of itself. More research is needed, they say,

to confirm their findings and to determine whether it would be

worthwhile to develop treatments to block ADAM9.

[to top of second column]

|

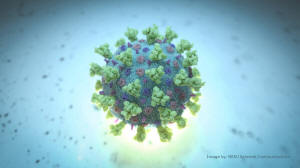

A computer image created by Nexu Science Communication together with

Trinity College in Dublin, shows a model structurally representative

of a betacoronavirus which is the type of virus linked to COVID-19,

better known as the coronavirus linked to the Wuhan outbreak, shared

with Reuters on February 18, 2020. NEXU Science Communication/via

REUTERS

Pregnant women get sub-par benefit from first vaccine

dose

Women who get the first dose of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine while

pregnant or breastfeeding need the second dose to bring their

protective benefit up to normal, according to a new study.

Researchers compared immune responses to the mRNA vaccines from

Moderna Inc or Pfizer Inc and partner BioNTech SE in 84 pregnant

women, 31 breastfeeding women, and 16 similarly-aged nonpregnant,

non-lactating women. After the first shot, everyone developed

antibodies against the coronavirus. But antibody levels were lower

in women who were pregnant or breastfeeding. Other features of the

immune response also lagged in the pregnant and lactating women

after the first dose but "caught up" to normal after the second

shot. In a report published last week in Science Translational

Medicine, the researchers explained that in order for a mother's

body to nurture the fetus, "substantial immunological changes occur

throughout pregnancy." The new findings suggest that pregnancy

alters the immune system's response to the vaccine. Given that

pregnant women are highly vulnerable to complications from COVID-19,

"there is a critical need" for them to get the second dose on

schedule, the researchers said.

Coronavirus found to infect fat cells

Obesity is a known risk factor for more severe COVID-19. One likely

reason may be that the virus can infect fat cells, researchers have

discovered. In lab experiments and in autopsies of patients who died

of COVID-19, they found the virus infects two types of cells found

in fat tissue: mature fat cells, called adipocytes, and immune cells

called macrophages. "Infection of fat cells led to a marked

inflammatory response, consistent with the type of immune response

that is seen in severe cases of COVID-19," said Dr. Catherine Blish

of Stanford University School of Medicine, whose team reported the

findings on bioRxiv on Monday ahead of peer review. "These

data suggest that infection of fat tissue and its associated

inflammatory response may be one of the reasons why obese

individuals do so poorly when infected with SARS-CoV-2," she said.

(Reporting by Nancy Lapid; Editing by Bill Berkrot)

[© 2021 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.] Copyright 2021 Reuters. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|