|

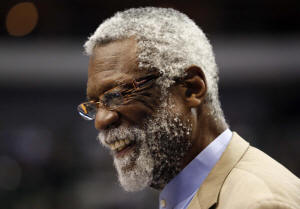

Russell, a five-time Most Valuable Player who was also outspoken

on racial issues, passed away peacefully with his wife Jeannine

by his side, according to a statement posted on his Twitter

account that did not state a cause of death.

"Bill Russell was the greatest champion in all of team sports,"

NBA Commissioner Adam Silver said in a statement.

"The countless accolades that he earned for his storied career

with the Boston Celtics – including a record 11 championships

and five MVP awards – only begin to tell the story of Bill's

immense impact on our league and broader society."

Russell became a superstar in the 1950s and '60s not with flashy

scoring plays but through dominating rebounding and intense

defensive play that reshaped the game. He also had what team

mate Tom Heinsohn called "a neurotic need to win".

The Celtics won 11 NBA titles in Russell's 13 years with the

team from 1956 through 1969. He was the player-coach on two of

those championship teams.

"To be the greatest champion in your sport, to revolutionize the

way the game is played, and to be a societal leader all at once

seems unthinkable, but that is who Bill Russell was," the

Celtics said in a statement.

"Bill Russell's DNA is woven through every element of the

Celtics organization, from the relentless pursuit of excellence,

to the celebration of team rewards over individual glory, to a

commitment to social justice and civil rights off the court.

"Our thoughts are with his family as we mourn his passing and

celebrate his enormous legacy in basketball, Boston, and

beyond."

DEFENSIVE GENIUS

The Russell-era Celtics teams were rich in talent. Heinsohn, Bob

Cousy, Frank Ramsey, Bill Sharman, Tom "Satch" Sanders, John

Havlicek, Don Nelson, Sam Jones and K.C. Jones, his old college

team mate, would all join him in the Basketball Hall of Fame, as

would their coach, Red Auerbach.

But Russell's rebounding and defense, especially his

shot-blocking, were unprecedented and set him apart. Russell,

who was spindly compared to opponents at the center position

when he came into the NBA, would leap to block opponents' shots

at a time when the prevailing defensive philosophy was that

players generally should not leave their feet.

"Russell defended the way Picasso painted, the way Hemingway

wrote," Aram Goudsouzian said in his book "King of the Court:

Bill Russell and the Basketball Revolution."

"In time, he changed how people understood the craft. Until

Russell, the game stayed close to the floor. No longer."

Russell averaged 15.1 points and 22.5 rebounds per game for his

career. He was the NBA's most valuable player in 1958, 1961,

1962, 1963 and 1965 and was a 12-time All-Star.

Despite the individual honors, Russell viewed "team" as a sacred

concept.

"For me, it didn't make any difference who did what as long as

we got it done," Russell said.

CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVIST

Off the court, Russell was opinionated and complicated. He had a

baleful glare but also a delightful cackling laugh. He was

intellectual and a "Star Trek" fan. Often surly or indifferent

to fans and hostile toward the media, he could be exceedingly

gracious with team mates and opponents. He refused to sign

autographs, saying he preferred to have conversations.

Russell often criticized Boston, a city with a history of racial

strife, and was one of the sports world's leading civil rights

activists in the 1950s and '60s. He was on the front row in

Washington in 1963 when Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his "I

Have a Dream" speech.

"Bill stood for something much bigger than sports: the values of

equality, respect and inclusion that he stamped into the DNA of

our league," said Silver.

"At the height of his athletic career, Bill advocated vigorously

for civil rights and social justice, a legacy he passed down to

generations of NBA players who followed in his footsteps.

"Through the taunts, threats and unthinkable adversity, Bill

rose above it all and remained true to his belief that everyone

deserves to be treated with dignity."

CELEBRATED RIVALRY

Russell had a celebrated rivalry with another NBA superstar,

Wilt Chamberlain, who played for the San Francisco/Philadelphia

Warriors, Philadelphia 76ers and Los Angeles Lakers. Chamberlain

was an athletic freak the likes of which had not been seen in

the NBA - muscular, exceptionally agile, 7-foot-1 inches tall

(2.16 meters) and the most prodigious scorer of his time.

Chamberlain and Russell, who was 3 to 4 inches (7.6 to 10 cm)

shorter, went head to head against each other in some epic

battles. Chamberlain almost always outscored him but Russell's

Celtics had an 86-57 record against Chamberlain's teams.

Chamberlain compiled the record-breaking personal statistics but

Russell ended up with more championship rings than fingers.

In 1965, Chamberlain became the first NBA player to earn a

$100,000 annual salary so Russell demanded - and got - a

contract from the Celtics that paid him $100,001. Yet the fierce

rivals were friends off the court, often dining at each other's

homes.

Russell was born Feb. 12, 1934, in West Monroe, Louisiana, and

was eight when his family moved to Oakland, California, seeking

more economic opportunity and an escape from the extreme racial

segregation of the U.S. South.

It was in Oakland that Russell's career as a winner began. His

high school team won two state championships and he led the

University of San Francisco to national titles in 1955 and '56.

Russell also was captain of the U.S. team that easily won the

gold medal at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne.

MEDAL OF FREEDOM

When the Celtics retired his No. 6, Russell's love of privacy

and belief in the team concept led him to demand a private

ceremony with coaches and team mates in an otherwise empty

arena. He declined to attend the 1972 ceremony at which his

number was retired in front of fans and also skipped his

induction ceremony at the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Russell returned to basketball as general manager and coach of

the Seattle SuperSonics from 1973 through 1977 and as coach of

the Sacramento Kings for part of the 1987-88 season.

Russell became semi-reclusive after his coaching career, saying,

"I wanted to be forgotten." He took tentative steps back into

the public arena beginning in the early 1990s, after becoming a

founding board member of MENTOR: the National Mentoring

Partnership. He said his mentoring effort was the "proudest

accomplishment in life."

Russell went on to make frequent public speaking appearances and

television commercials and even showed up when the Celtics

dedicated a statue of him in Boston's City Hall Plaza in 2013.

In 2011, President Barack Obama cited Russell's dedication to

mentoring when he awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom,

which Russell called the second greatest personal honor of his

life. The first, he said, was when his 77-year-old father told

him that he was proud of him.

Russell, who lived in Mercer Island, Washington, was married

three times and had three children.

(Writing and reporting by Bill Trott; Additional reporting by

Frank Pingue in Toronto; Editing by David Gregorio and Toby

Davis)

[© 2022 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |

|