Energy politics cloud Mexican bid to join U.S. semiconductor rush

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[December 14, 2022] By

Dave Graham [December 14, 2022] By

Dave Graham

MEXICO CITY (Reuters) - Mexico's hopes of reaping an investment windfall

from a U.S. drive to boost North American semiconductor production risk

foundering on companies' concerns over energy supply, overdependence on

fossil fuels, and a lack of financial incentives.

U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said in September a $52.7 billion

U.S. bill known as the Chips Act would also create "significant

opportunities" for Mexico in the energy and water-intensive

semiconductor industry.

But according to interviews with over a dozen people privy to investment

discussions, if Mexico does not move quickly to improve power

transmission networks and renewable energy access, as well as craft

competitive incentives, it may lose out.

The United States is building huge plants that make high-tech chips, the

most expensive part of the semiconductor business. Mexico, meanwhile,

has its sights on more accessible parts of the supply chain like design,

packaging and testing.

To create those jobs, the country must allay business fears over

electricity supply sparked by President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador's

campaign to give market control to Mexico's cash-strapped, fossil-fuel

dependent national energy companies.

His pursuit of "energy sovereignty" by helping utility Comision Federal

de Electricidad and state oil firm Petroleos Mexicanos while limiting

privately-funded renewable output has flummoxed manufacturers trying to

lower their carbon footprint.

"Mexico's current energy policy is severely undercutting the country's

ability to attract new investment, especially when it comes to strategic

sectors such as the semiconductor industry," said Neil Herrington,

senior vice president for the Americas at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Lopez Obrador's office did not reply to requests for comment for this

story.

Used in industries from telecoms, defense and carmaking to computing,

semiconductors hit the headlines during the COVID-19 pandemic when

supply dried up, causing serious production bottlenecks in global

manufacturing.

Unlike the United States, Mexico has yet to spell out what inducements

it will offer firms to help North America reduce reliance on

semiconductor hubs like Taiwan in light of protracted uncertainty in

U.S.-China relations.

"The government has done almost nothing on attracting investment and

incentives," said Roberto Arechederra, economy minister of the

opposition-run western state of Jalisco, whose capital Guadalajara is

known as Mexico's Silicon Valley.

Lopez Obrador, a leftist resource nationalist, says conditions for

investors are "unbeatable", and points to foreign direct investment

headed for its best year in nearly a decade.

But gross fixed investment remains 11% lower than when he was elected in

mid-2018, official data show.

Officials, executives and lawmakers say without a better power grid, the

Mexican semiconductor push will struggle. U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer

Granholm had in January already warned Mexico's treatment of energy

firms could hamper growth.

"You can't do stuff like that if you want to be a team player," said

Henry Cuellar, a Democratic congressman who chairs the U.S.-Mexico

Interparliamentary Group. "Especially in being part of a North American

supply chain. It's all inter-related."

Mexico has vowed to present nearshoring incentives by the end of

February, and Economy Minister Raquel Buenrostro said last week a

planned business corridor in southern Mexico could become a center for

semiconductor investment.

States like Jalisco, home to a major Intel Corp facility, are offering

their own incentives like tax breaks and cheap land, said minister

Arechederra.

Much of the impetus for cooperation on semiconductors originated in

Mexico, executives say.

In June 2021, Carlos Salazar, then-president of Mexico's Business

Coordinating Council, pitched the idea to U.S. Commerce chief Raimondo

on a visit to Washington, he told Reuters.

Pledges to strengthen supply chains followed, and in August 2022 Mexico

held a conference targeting semiconductor investment with firms

including Intel and Skyworks Solutions Inc, a major employer in the

border city of Mexicali.

[to top of second column] |

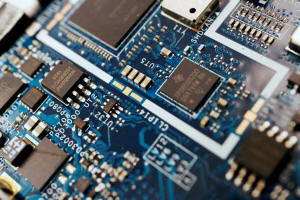

Semiconductor chips are seen on a

circuit board of a computer in this illustration picture taken

February 25, 2022. REUTERS/Florence Lo/Illustration

Josep Marce, Skyworks' vicepresident of operations in Mexico, urged

the country to seize the window of opportunity.

That means Mexico needs to keep investing in energy and water

infrastructure, and do so sustainably, he told Reuters, pointing to

clients' pledges to help tackle global warming.

While industry giants such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co

Ltd and Intel have announced multibillion dollar investments on the

U.S. side of the border, Mexico has yet to unveil major projects

that could supply those factories.

"The United States is thinking regionally, Mexico is still thinking

as one country," said Luis Manuel Hernandez, head of Mexican

manufacturing export industry group Index. "If we want to be at the

big table, we need to take different decisions."

GOLDEN AGE?

In July, tensions over energy boiled over into a formal dispute with

United States and Canada, who argue Mexico is discriminating against

their companies.

On Monday, Mexico's government said it wanted the spat resolved to

give companies confidence to invest in the country.

Lopez Obrador says past, corrupt governments rigged the energy

market to favor private interests at the state's expense.

In Jalisco, national energy policy has put on hold seven private

renewable power projects - five solar and two wind - encompassing

$1.1 billion in total investment, according to figures from the

state's energy agency.

Businesses are taking note, especially in carmaking.

Julian Eaves at CW Bearing, a Chinese-owned automotive supplier in

central Mexico, said firms want to leverage the country's location

and competitive labor costs.

But winning new business depends on firms showing customers how they

will lower global emissions -- a goal government policies are

hindering, he said.

"This is a potential golden age for Mexico," said Eaves, CW's

director of operations and manufacturing for North America. "But it

hasn't evolved to meet market requirements."

Francisco Fiorentini, executive vice president of industrial park

developer PIMSA in Mexicali, estimated that if government policy was

not inhibiting power supply, foreign investment in the state of Baja

California could have been up to 45% higher.

Mexicali became a warning beacon for investors in 2020 when Lopez

Obrador canceled a largely completed billion-dollar Constellation

Brands brewery there after holding a referendum against the plant,

arguing it jeopardized water supply.

Hernandez of Index said Baja California and Chihuahua, another

border state closely integrated with the U.S. economy, had during

the past three years lacked about 1.8 Gigawatts of combined power

supply to capitalize on existing demand.

Mexico has made progress working with academia to accelerate

training of engineers and analyzing where U.S. firms could convert

factory floors to focus on assembly, packaging and testing of

semiconductors, said Monica Duhem, who until October oversaw efforts

at the economy ministry to lure investment.

But though the president would privately reassure businesses that

investing in Mexico was worthwhile, his frequent public

denunciations of energy firms fed doubts, she said.

"Multinationals said to me: 'What's your strategy on transitioning

to renewable energy?'" Duhem recalled.

There are signs policy is shifting.

Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard said recently Mexico needed to

invest $50 billion to double its renewable power capacity by 2030 as

he discussed investment in semiconductors with executives in the

border city of Tijuana.

"If you're not producing with clean energy," he said, "you won't be

able to export to the United States."

(Reporting by Dave Graham; editing by Claudia Parsons)

[© 2022 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |