U.S. lab hits fusion milestone raising hopes for clean power

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[December 14, 2022]

By Timothy Gardner [December 14, 2022]

By Timothy Gardner

WASHINGTON (Reuters) -U.S. scientists on Tuesday revealed a breakthrough

on fusion energy that could one day help curb climate change if

companies can scale up the technology to a commercial level in the

coming decades.

Scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Lab in California on Dec.

5 for the first time briefly achieved a net energy gain in a fusion

experiment using lasers, the U.S. Energy Department said. The scientists

focused a laser on a target of fuel to fuse two light atoms into a

denser one, releasing the energy.

Kimberly Budil, the director of Lawrence Livermore, told reporters at an

Energy Department event that science and technology hurdles mean

commercialization is probably not five or six decades away, but sooner.

"With concerted effort and investment, a few decades of research on the

underlying technologies could put us in a position to build a power

plant," Budil said.

Scientists have known for about a century that fusion powers the sun and

have pursued developing fusion on Earth for decades.

The experiment briefly achieved what's known as fusion ignition by

generating 3.15 megajoules of energy output after the laser delivered

2.05 megajoules to the target, the Energy Department said.

Arati Prabhakar, director of the White House Office of Sciences and

Technology Policy, who heard about fusion at Livermore when she worked

there briefly in 1978 as a teenager, said the experiment represents a

"tremendous example of what perseverance can achieve."

Nuclear scientists outside the lab said the achievement will be a major

stepping stone, but there is much more science to be done before fusion

becomes commercially viable.

Tony Roulstone, a nuclear energy expert at the University of Cambridge,

estimated that the energy output of the experiment was only 0.5% of the

energy that was needed to fire the lasers in the first place.

[to top of second column]

|

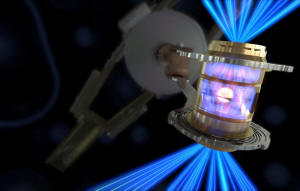

National Ignition Facility’s laser

energy is converted into x-rays inside the hohlraum, which then

compress a fuel capsule until it implodes, creating a high

temperature, high pressure plasma in an undated photograph at

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory federal research facility in

Livermore, California, U.S. John Jett and Jake Long/Lawrence

Livermore National Laboratory/Handout via REUTERS

.jpg)

"Therefore, we can say that this result ... is a success of the

science – but still a long way from providing useful, abundant,

clean energy," Roulstone said. In order to become commercial, a

power plant would have to produce enough energy to power the lasers

and to achieve ignition continuously.

"This is one igniting capsule (of fuel) one time," Budil said about

the experiment. To realize commercial fusion energy you have to ...

be able to produce many, many fusion ignition events per minute."

The electricity industry cautiously welcomed the step, though

emphasized that in order to carry out the energy transition, fusion

should not slow down efforts on building out other alternatives like

solar and wind power, battery storage and nuclear fission.

"It's the first step that says 'Yes, this is not just fantasy, this

can be done, in theory,'" said Andrew Sowder, a senior technology

executive at EPRI, a nonprofit energy research and development

group.

Debra Callahan, who worked at Lawrence Livermore until late this

year and is now a senior scientist at Focused Energy, said the lab's

results will help companies figure out how to make lasers more

efficient. "Everyone is excited about what's been achieved and

what's in the future."

Focused Energy is one of dozens of companies working to

commercialize fusion energy that have raised about $5 billion in

private and government funding, with more than $2.8 billion coming

in the 12 months before June of this year, according to the Fusion

Industry Association. Several, including Commonwealth Fusion

Systems, seek to use powerful magnets instead of lasers.

(Reporting by Timothy Gardner; Editing by Andrea Ricci and Lisa

Shumaker)

[© 2022 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |