U.S. grocery shortages deepen as pandemic dries supplies

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[January 15, 2022] By

Siddharth Cavale and Christopher Walljasper [January 15, 2022] By

Siddharth Cavale and Christopher Walljasper

(Reuters) - High demand for groceries

combined with soaring freight costs and Omicron-related labor shortages

are creating a new round of backlogs at processed food and fresh produce

companies, leading to empty supermarket shelves at major retailers

across the United States.

Growers of perishable produce across the West Coast are paying nearly

triple pre-pandemic trucking rates to ship things like lettuce and

berries before they spoil. Shay Myers, CEO of Owyhee Produce, which

grows onions, watermelons and asparagus along the border of Idaho and

Oregon, said he has been holding off shipping onions to retail

distributors until freight costs go down.

Myers said transportation disruptions in the last three weeks, caused by

a lack of truck drivers and recent highway-blocking storms, have led to

a doubling of freight costs for fruit and vegetable producers, on top of

already-elevated pandemic prices. "We typically will ship, East Coast to

West Coast – we used to do it for about $7,000," he said. "Today it’s

somewhere between $18,000 and $22,000."

Birds Eye frozen vegetables maker Conagra Brands' CEO Sean Connolly told

investors last week that supplies from its U.S. plants could be

constrained for at least the next month due to Omicron-related absences.

Earlier this week, Albertsons CEO Vivek Sankaran said he expects the

supermarket chain to confront more supply chain challenges over the next

four to six weeks as Omicron has put a dent in its efforts to plug

supply chain gaps.

Shoppers on social media complained of empty pasta and meat aisles at

some Walmart stores; a Meijer store in Indianapolis was swept bare of

chicken; a Publix in Palm Beach, Florida was out of bath tissue and home

hygiene products while Costco reinstated purchase limits on toilet paper

at some stores in Washington state.

The situation is not expected to abate for at least a few more weeks,

Katie Denis, vice president of communications and research at the

Consumer Brands Association said, blaming the shortages on a scarcity of

labor.

The consumer-packaged goods industry is missing around 120,000 workers

out of which only 1,500 jobs were added last month, she said, while the

National Grocer’s Association said that many of its grocery store

members were operating with less than 50% of their workforce capacity.

[to top of second column] |

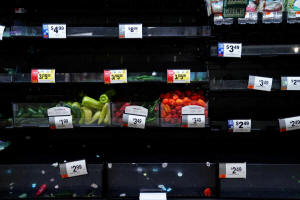

Produce shelves are seen nearly empty at a Giant Food grocery store

as the U.S. continues to experience supply chain disruptions in

Washington, U.S., January 9, 2022. REUTERS/Sarah Silbiger

U.S. retailers are now facing roughly 12% out of stock levels on food,

beverages, household cleaning and personal hygiene products compared to 7-10% in

regular times.

The problem is more acute with food products where out of stock levels are

running at 15%, the Consumer Brands Association said.

SpartanNash, a U.S. grocery distributor, last week said it has become harder to

get supplies from food manufacturers, especially processed items like cereal and

soup.

Consumers have continued to stock up on groceries as they hunker down at home to

curb the spread of the Omicron-variant. Denis said demand over the last five

months has been as high or higher than it had been in March 2020 at the

beginning of the pandemic. Similar issues are being seen in other parts of the

world.

In Australia, grocery chain operator Woolworths Group, said last week that more

than 20% of employees at its distribution centers are off work because of

COVID-19. In the stores, the virus has put at least 10% of staff out of action.

The company, on Thursday, reinstated a limit of two packs per customer across

toilet paper and painkillers nationwide both in-store and online to deal with

the staffing shortage.

In the U.S., recent snow and ice storms that snared traffic for hours along the

East Coast also hampered food deliveries bound for grocery stores and

distribution hubs. Those delays rippled across the country, delaying shipment on

fruit and vegetables with a limited shelf life.

While growers with perishable produce are forced to pay inflated shipping rates

to attract limited trucking supplies, producers like Myers are choosing to wait

for backlogs to ease.

"The canned goods, the sodas, the chips – those things sat, because they weren’t

willing to pay double, triple the freight, and their stuff doesn’t go bad in

four days," he said.

(Additional reporting by Praveen Paramasivam; Editing by Vanessa O'Connell and

Diane Craft)

[© 2022 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|