Scientists reveal origin of mammal evolution milestone: warm-bloodedness

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[July 21, 2022]

By Will Dunham [July 21, 2022]

By Will Dunham

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Scientists have

answered a longstanding question about mammalian evolution, examining

ear anatomy of living and extinct mammals and their close relatives to

determine when warm-bloodedness - a trait integral to the lineage's

success - first emerged.

Researchers said on Wednesday that the reduced size of inner ear

structures called semicircular canals - small, fluid-filled tubes that

help in keeping balance - in fossils of mammal forerunners showed that

warm-bloodedness, called endothermy, arose roughly 233 million years ago

during the Triassic Period.

These first creatures that attained this milestone, called mammaliamorph

synapsids, are not formally classified as mammals, as the first true

mammals appeared roughly 30 million years later. But they had begun to

acquire traits associated with mammals.

Endothermy evolved at a time when important features of the mammal body

plan were falling into place, including whiskers and fur, changes to the

backbone related to gait, the presence of a diaphragm, and a more

mammal-like jaw joint and hearing system.

"Endothermy is a defining feature of mammals, including us humans.

Having a quasi-constant high body temperature regulates all our actions

and behaviors, from food intake to cognition, from locomotion to the

places where we live," said paleontologist Ricardo Araújo of the

University of Lisbon's Institute of Plasmas and Nuclear Fusion, co-lead

author of the study published in the journal Nature.

The high metabolisms of mammal bodies maintain internal temperature

independent of their surroundings. Cold-blooded animals like lizards

adopt strategies like basking in the sun to warm up.

Mammalian endothermy arrived at an eventful evolutionary moment, with

dinosaurs and flying reptiles called pterosaurs - creatures that long

would dominate ecosystems - first appearing at about that time.

Endothermy offered advantages.

"Run faster, run longer, be more active, be active through longer

periods of the circadian cycle, be active through longer periods of the

year, increase foraging area. The possibilities are endless. All this at

a great cost, though. More energy requires more food, more foraging, and

so on. It is a fine balance between the energy you spend and the energy

you intake," Araújo said.

The mammalian lineage evolved from cold-blooded creatures, some boasting

exotic body plans like the sail-backed Dimetrodon, mixing reptile-like

traits like splayed legs and mammal-like traits like the arrangement of

certain jaw muscles.

[to top of second column]

|

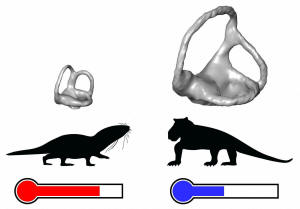

Size differences between inner ears (in grey) of warm-blooded

mammaliamorphs (on the left) and cold-blooded, earlier synapsids (on

the right). Inner ears are compared for animals of similar body

sizes.Romain David and Ricardo Araujo/Handout via REUTERS.

Endothermy emerged relatively quickly, in perhaps

less than a million years, rather than a longer, gradual process,

said paleontologist and study co-lead author Romain David of the

Natural History Museum in London.

An early example was a vaguely weasel-like species,

Pseudotherium argentinus, in Argentina about 231 million years ago.

The later true mammals were the ancestors of today's three mammalian

groups: placentals, marsupials and monotremes.

"Given how central endothermy is to so many aspects of the body

plan, physiology and lifestyle of modern mammals, when it evolved in

our ancient ancestors has been a really important unsolved question

in paleontology," said paleontologist and study co-author Ken

Angielczyk of the Field Museum in Chicago.

Determining when endothermy originated through fossils has been

tough. As Araújo noted: "We cannot stick thermometers in the armpit

of your pet Dimetrodon, right?"

The inner ear provided a solution. The viscosity, or runniness, of

inner ear fluid - and all fluid - changes with temperature. This

fluid in cold-blooded animals is cooler and thicker, necessitating

wider canals. Warm-blooded animals have less viscous ear fluid and

smaller semicircular canals.

The researchers compared semicircular canals in 341 animals, 243

extant and 64 extinct. This showed endothermy arriving millions of

years later than some prior estimates.

Mammals played secondary roles in ecosystems dominated by dinosaurs

before taking over after the mass extinction event 66 million years

ago. Among today's animals, mammals and birds are warm-blooded.

"It is maybe too far-fetched, but interesting, to think that the

onset of endothermy in our ancestors may have ultimately led to the

construction of the Giza pyramids or the development of the

smartphone," Araújo said. "If our ancestors would have not become

independent of environmental temperatures, these human achievements

would probably not be possible."

(Reporting by Will Dunham, Editing by Rosalba O'Brien)

[© 2022 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|