In an ancient shark showdown, 'Jaws' may have doomed 'The Meg'

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[June 01, 2022] By

Will Dunham [June 01, 2022] By

Will Dunham

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - An examination of

the zinc content of teeth from sharks both living and extinct is

providing clues about the demise of the largest-known shark, indicating

the mighty megalodon may have been out-competed by the great white shark

in ancient seas.

Researchers assessed the ratio of two forms of the mineral zinc in an

enamel-like material called enameloid that comprises the outer part of

shark teeth. This ratio enabled them to infer the diets of the sharks

and gauge their position on the marine food chain.

They found that while the megalodon may have been alone atop the food

chain for millions of years, the great white shark's arrival about 5.3

million years ago added another apex predator hunting similar prey.

This competition for food resources featured two animals now lodged in

the popular imagination - with the great white featured in the

blockbuster 1975 film "Jaws" and its sequels and the megalodon starring

in the popular 2018 movie "The Meg."

Megalodon, whose scientific name is Otodus megalodon, appeared about 15

million years ago and went extinct about 3.6 million years ago. It was

one of the largest predators in Earth's history, reaching at least 50

feet (15 meters) and possibly 65 feet (20 meters) in length while

feeding on marine mammals including whales.

The great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, reaches at least 20 feet

(6 meters) long, and may have been the more agile of the two.

"The megalodon co-existed with the great white shark during the time

frame called the early Pliocene, and our zinc data suggest that they

seem to have indeed occupied the same position in the food chain," said

paleobiologist Kenshu Shimada of DePaul University in Chicago, a

co-author of the study published on Tuesday in the journal Nature

Communications.

"There have been multiple hypotheses as to why megalodon went extinct.

Traditional hypotheses have attributed this to climate change and the

decline in food sources. However, a recently proposed hypothesis

contends that megalodon lost the competition with the newly evolved

great white shark. Our new study appears to support this proposition. It

is also entirely possible that a combination of multiple factors may

have been at play," Shimada said.

[to top of second column]

|

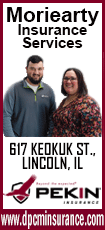

Tooth size comparison between the extinct shark megalodon and a

modern great white shark is seen in this undated image. Max Planck

Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology/Handout via REUTERS.

The researchers said it is not thought that the great

white actually hunted its larger cousin.

The study involved teeth from 20 living shark species and 13 fossil

species, signaling their position on the food chain.

"At the bottom of the food chain are our 'primary producers,' which

are photosynthetic organisms like phytoplankton that convert solar

energy to food. At the top of the food chain are the apex predators

like great white sharks, who have no predators except for humans,

while in between we have herbivores, omnivores and lower-level

carnivores," said study co-author Michael Griffiths, a geochemist

and paleoclimatologist at William Paterson University in New Jersey.

Today's great white sharks hunt sea turtles as well as marine

mammals including seals, sea lions, porpoises, dolphins and small

whales.

The study indicated that Carcharodon hastalis, considered a direct

ancestor of the great white, was not positioned as high in the food

chain, likely feeding commonly on fish rather than marine mammals.

For a creature that played a vital role in marine ecosystems for

millions of years, much remains mysterious about the megalodon.

Because shark skeletons are cartilaginous rather than bony, they do

not lend themselves well to fossilization, making it hard to know

precisely what megalodon looked like. However, innumerable megalodon

tooth fossils have been found around the world.

"Megalodon is typically portrayed as a super-sized, monstrous shark

in novels and films, but the reality is that we still know very

little about this extinct shark," Shimada said.

(Reporting by Will Dunham, Editing by Rosalba O'Brien)

[© 2022 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|