Russia pushed into historic default by sanctions

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[June 27, 2022] By

Karin Strohecker, Andrea Shalal and Emily Chan [June 27, 2022] By

Karin Strohecker, Andrea Shalal and Emily Chan

LONDON (Reuters) -Russia defaulted on its

international bonds for the first time in more than a century, the White

House said, as sweeping sanctions have effectively cut the country off

from the global financial system, rendering its assets untouchable.

The Kremlin, which has the money to make payments thanks to oil and gas

revenues, swiftly rejected the claims, and has accused the West of

driving it into an artificial default.

Earlier, some bondholders said they had not received overdue interest on

Monday following the expiry of a key payment deadline on Sunday.

Russia has struggled to keep up payments on $40 billion of outstanding

bonds since its invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24.

"This morning's news around the finding of Russia's default, for the

first time in more than a century, situates just how strong the actions

are that the U.S., along with allies and partners have taken, as well as

how dramatic the impact has been on Russia's economy," the U.S. official

said on the sidelines of a G7 summit in Germany.

Russia's efforts to avoid what would be its first major default on

international bonds since the Bolshevik revolution more than a century

ago hit a roadblock in late May when the U.S. Treasury Department's

Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) effectively blocked Moscow from

making payments.

"Since March we thought that a Russian default is probably inevitable,

and the question was just when," Dennis Hranitzky, head of sovereign

litigation at law firm Quinn Emanuel, told Reuters ahead of the Sunday

deadline.

"OFAC has intervened to answer that question for us, and the default is

now upon us."

A formal default would be largely symbolic given Russia cannot borrow

internationally at the moment and doesn't need to thanks to plentiful

oil and gas export revenues. But the stigma would probably raise its

borrowing costs in future.

The payments in question are $100 million in interest on two bonds, one

denominated in U.S. dollars and another in euros, that Russia was due to

pay on May 27. The payments had a grace period of 30 days, which expired

on Sunday.

Russia's finance ministry said it made the payments to its onshore

National Settlement Depository (NSD) in euros and dollars, adding it had

fulfilled obligations.

In a call with reporters, Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said the

fact that payments had been blocked by Euroclear because of Western

sanctions on Russia was "not our problem".

Clearing house Euroclear did not respond to a request for comment.

Some Taiwanese holders of the bonds had not received payments on Monday,

sources told Reuters.

With no exact deadline specified in the prospectus, lawyers say Russia

might have until the end of the following business day to pay these

bondholders.

Credit ratings agencies usually formally downgrade a country's credit

rating to reflect default, but this does not apply in case of Russia as

most agencies no longer rate the country.

LEGAL TANGLE

The legal situation surrounding the bonds looks complex.

[to top of second column] |

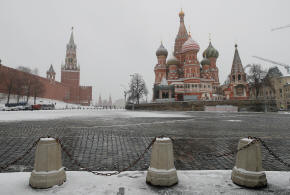

The clock on Spasskaya tower showing the time at noon, is pictured

next to Moscow?s Kremlin, and St. Basil?s Cathedral, March 31, 2020.

REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov

Russia's bonds have been issued with an unusual variety of terms, and an

increasing level of ambiguities for those sold more recently, when Moscow was

already facing sanctions over its annexation of Crimea in 2014 and a poisoning

incident in Britain in 2018.

Rodrigo Olivares-Caminal, chair in banking and finance law at Queen Mary

University in London, said clarity was needed on what constituted a discharge

for Russia on its obligation, or the difference between receiving and recovering

payments.

"All these issues are subject to interpretation by a court of law," Olivares-Caminal

told Reuters.

In some ways, Russia has been in default already.

A committee on derivatives has ruled a "credit event" had occurred on some of

Russia's securities, which triggered a payout on some of Russia's credit default

swaps - instruments used by investors to insure against debt default.

This was triggered by Russia failing to make a $1.9 million payment in accrued

interest on a payment that had been due in early April.

Until the Ukraine invasion, a sovereign default had seemed unthinkable, with

Russia having an investment grade rating shortly before that point. A default

would also be unusual as Moscow has the funds to service its debt.

The U.S. Treasury's OFAC had issued a temporary waiver, known as a general

licence 9A, in early March to allow Moscow to keep paying investors. The U.S.

let the waiver expire on May 25 as Washington tightened sanctions on Russia,

effectively cutting off payments to U.S. investors and entities.

The lapsed OFAC licence is not Russia's only obstacle. In early June, the

European Union imposed sanctions on the NSD, Russia's appointed agent for its

Eurobonds.

Moscow has tried in the past few days to find ways of dealing with upcoming

payments and avoid a default.

President Vladimir Putin signed a decree last Wednesday to launch temporary

procedures and give the government 10 days to choose banks to handle payments

under a new scheme, suggesting Russia will consider its debt obligations

fulfilled when it pays bondholders in roubles and onshore in Russia.

"Russia saying it's complying with obligations under the terms of the bond is

not the whole story," Zia Ullah, partner and head of corporate crime and

investigations at law firm Eversheds Sutherland told Reuters.

"If you as an investor are not satisfied, for instance, if you know the money is

stuck in an escrow account, which effectively would be the practical impact of

what Russia is saying, the answer would be, until you discharge the obligation,

you have not satisfied the conditions of the bond."

(Reporting by Karin Strohecker in London, Andrea Shalal in Elmau and Emily Chan

in Taipei and Sujata Rao in London; Editing by David Holmes, Emelia

Sithole-Matarise, Simon Cameron-Moore and Jane Merriman)

[© 2022 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|