|

New RiverWatch volunteers learn

how to monitor stream at Creekside

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[March 31, 2022] [March 31, 2022]

On March 26, six people attended a training to become Illinois

RiverWatch volunteers. These volunteers, known as citizen

scientists, collect and identify organisms in streams to help

monitor its water quality.

As the RiverWatch website says, “The Illinois RiverWatch safeguards

the future of Illinois rivers and streams through stewardship,

education and sound science.”

The training was led by Stream Ecologist and RiverWatch Director

Danelle Haake, who trains citizen scientists how to monitor stream

habitats and water quality.

The citizen scientists do the monitoring through habitat and

biological surveys where they collect and identify small stream

organisms, known as macroinvertebrates or aquatic invertebrates.

Using data on the types and amounts of these organisms helps citizen

scientists calculate the quality of a stream.

Those in attendance were Leslie, Mike and Stephen Starasta, Julie

and Laney Saylor and Pam Moriearty. Leslie Starasta has done past

RiverWatch trainings and served as a Citizen Scientist, but said she

wanted to take this training as a refresher course. Moriearty has

been monitoring Sugar Creek and logging data since 2014.

Dr. Dennis Campbell was on hand to assist with activities as needed.

He said Sugar Creek has more species in it than any other mid-level

stream in Illinois.

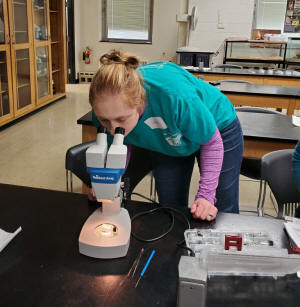

Julie Saylor

examining critters through a mictoscope

Attendees spent the morning at Lincoln College where they learned

about various macroinvertebrates. After learning about these

macroinvertebrates, attendees were able to view samples from a kit

through a microscope. These samples included flatworms, aquatic

sowbugs, leeches, flatworms, scuds, and midges.

The afternoon was then spent at Lincoln College’s Dr. G. Dennis

Campbell Creekside Outdoor Center for Environmental Education (Creekside)

along Sugar Creek where everyone received hands-on instruction on

field techniques for creek monitoring.

RiverWatch volunteers have been monitoring Sugar Creek for several

years and RiverWatch recently named Creekside its 2021 Partner of

the Year. A January 28, 2022, Lincoln Daily News article said, “In

its selection of Creekside for this award, the Illinois RiverWatch

Network noted that Creekside has supported volunteers conducting

annual RiverWatch surveys, sponsored RiverWatch activities with

Master Naturalist volunteers and 4-H youth groups, and participated

in public communication efforts about research findings. Creekside

has also organized public Earth Day celebrations and nature

festivals that promote RiverWatch priorities within the local

agricultural community.”

In the afternoon activities, part of the training consisted of

putting a little ball in the stream to measure the flow and

distance. By taking the feet per second and dividing it by the

amount of time it takes the ball to float so many feet, one can

measure the flow of the water.

Participants were also shown how to monitor five different habitats:

riffles, leaf pack, snag, jab and sediment.

Haake trained everyone to collect the aquatic invertebrates from

these habitats and identify what they find. The volunteer scientists

then record the data, which helps them calculate stream quality

using what is called a Macroinvertebrate Biotic Index.

Haake explained and demonstrated various methods for collecting

samples from different habitats. She then had volunteers collect

samples from a riffle (shallow area) and leaf pack (clump of

leaves).

Stephen Starasta and

Danelle Haake collecting samples from a riffle

To collect samples from the riffle, a “netter” places the net

against the bottom of the streambed. A second person, called a

“kicker,” then picks up large rocks and rubs them around to get the

“aquatic invertebrates” off the rock. Next, the “kicker” will

shuffle and kick their feet from side to side to get the “aquatic

invertebrates” off the smaller rocks. Finally, the “netter” must

push the net upstream out of the water and put any aquatic

invertebrates caught into a bucket.

[to top of second column] |

Pam Moriearty and Leslie Starsta

collecting samples from a leaf pack

For the leaf pack, the “netter” holds the net downstream of the leaf pack and

the “kicker” grabs part of the leaf pack and shakes it in front of the open net,

dislodging the aquatic invertebrates and letting the flow carry them into the

net. Some leaves from the leaf pack are also added to the net. Ideally, they do

not put the whole leaf pack in the net because that might make the sorting

process take a very long time as the volunteers look on both sides of each leaf.

These leaves and aquatic invertebrates in the net are added to the same bucket

as the others.

Haake also explained how to sort what has been collected.

After samples are collected, volunteers pull handfuls at a time of the contents

of the bucket (including leaves, twigs, rocks, silt, and invertebrates) and sort

it in a pan of water. Any material with a large surface should be examined to

find any aquatic invertebrates that might be attached. All the invertebrates

found should be put in the pan with the grid. Once the larger material and

hiding places are gone, any invertebrates remaining in the pan should be found

and transferred to the gridded pan.

Once most of the solid material has been removed from the bucket, the remaining

material (mostly water and small sediments) can be poured through the net. Rinse

the bucket and pour the rinse water through the net until the bucket is clean.

Then check the inside of the net for invertebrates and transfer those found to

the gridded pan.

If there are 100 invertebrates or less in the gridded pan, all the invertebrates

are put in a collection jar containing rubbing alcohol.

Gridded pan for sorting aquatic

invertebrates

If there are more than 100, volunteers can opt to subsample their collected

invertebrates using the numbers of the grid. The volunteer must select a number

from the random number cup provided with the kit, then place all the

invertebrates in the square with that number into the collection jar, counting

as they go. This process is repeated until at least 100 invertebrates are

collected.

If there are any types of invertebrates that were not collected as part of the

subsampling, one of each type should be taken and added to the collection jar.

If the invertebrates are moving quickly in the gridded pan, adding a few capfuls

of soda water to the pan slows them down.

Aquatic invertebrates found on a

leaf

In the samples collected Saturday, there were not many aquatic

macroinvertebrates. However, in their samples, the participants were able to see

sowbugs and midge worms.

Once RiverWatchers (citizen scientists) have been trained, they can adopt a

stream location to monitor and conduct habitat and biological surveys. The

primary monitoring period is May and June. The citizen scientists then send to

the RiverWatch office to ensure the data collected is high quality.

[Angela Reiners] |