Contextualizing cash bail’s end

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[November 05, 2022]

By JERRY NOWICKI

Capitol News Illinois

jnowicki@capitolnewsillinois.com

SPRINGFIELD – While a new law overhauling

Illinois’ system of pretrial detention continues to face scrutiny ahead

of its Jan. 1 implementation date, new research suggests that the old

cash-based system “results in much less pretrial detention than is

generally assumed.” SPRINGFIELD – While a new law overhauling

Illinois’ system of pretrial detention continues to face scrutiny ahead

of its Jan. 1 implementation date, new research suggests that the old

cash-based system “results in much less pretrial detention than is

generally assumed.”

That’s according to the Loyola University of Chicago Center for Criminal

Justice, which has been measuring the potential effects of the provision

commonly referred to as the Pretrial Fairness Act, which will abolish

cash bail come Jan. 1.

“What we’ve found is that, while it’s true that many people are jailed

under the current cash bail system, most jail stays are brief,”

researchers wrote in an Oct. 26 brief that examined data from six

counties. “Most people pass through jails, being held for relatively

short periods before bonding out — and that includes people charged with

the kinds of serious offenses that are designated ‘detainable’ under the

PFA.”

The research is nonpartisan and not conducted for advocacy purposes. It

received funding from the National Institute of Justice, which is a

research arm of the U.S. Department of Justice.

David Olson, a Loyola professor and Center co-director, spoke to Capitol

News Illinois for an episode of the Capitol Cast podcast. Below is a

list of questions covered in the conversation, along with other context

from CNI’s previous reporting on the topic.

How will pretrial detention change under the new law?

The PFA, passed in 2021 as part of the SAFE-T Act criminal justice

reform, will end the wealth-based system that decides whether an

individual is released from custody while they await trial.

It replaces it with one that allows judges greater authority to detain

individuals who are accused of violent crimes and deemed a danger to the

community or a risk of fleeing prosecution. But the new system also

limits judicial discretion when it comes to lesser, non-violent

offenses.

Under current law, bail hearings typically occur within 72 hours of

arrest and last fewer than five minutes. Prosecutors detail the

defendant’s charges and may recommend a bail amount. The judge then

decides the conditions of their release, including how much money, if

any, the defendant must post before their release.

“The concern is that in in some counties, there's not sufficient time

spent considering the decision at hand, …there isn't adequate or

sufficient legal representation at that point where an important

decision about liberty is being made,” Olson said.

The PFA, he said, was designed to make detention hearings more

deliberative.

That’s important, he said, because the subjects of the law are

defendants who have only been charged with, not convicted of, a crime.

The new process will allow a prosecutor to petition the court for

pretrial detention and a defendant is given the right to legal

representation at their first hearing, with the detention hearing

typically taking place within 24 or 48 hours of the first appearance in

court.

Will more defendants walk free while awaiting trial because of the

new law?

Olson said the research can’t predict whether more or fewer people will

be jailed while awaiting trial once the PFA takes effect, but the makeup

of jail populations is likely to change. It’s likely, researchers found,

that lower-level defendants will spend less time in jail, while stays

may get longer for those accused of violent crime because they can no

longer free themselves on bail.

One study estimated that a judge would not have been able to detain the

defendant in 56 percent of arrests that occurred statewide in 2020 and

2021 had the PFA been in place.

But another analysis showed only 19 percent of individuals with pending

felony cases were in jail custody while awaiting trial on average from

2017 through 2019, with another 17 percent on electronic monitoring or

pretrial supervision.

That means about 64 percent of individuals awaiting trial for felony

charges over that timespan were living in the community without any sort

of supervision, the study found.

“The important caveat to that, and I think what the law seeks to

address, is that they spend some time in jail,” Olson said. “And even if

they spent a few days in jail, it's disruptive to their life. And we

didn't really achieve anything if we were thinking we were achieving

public safety, because we only held them for one or two days before

(they posted bond).”

Another study of Cook County data showed individuals charged with an

offense that would be non-detainable under the PFA paid an average of

$1,646 to be released from jail in 2021. Individuals who could be held

as flight risks under the PFA were required to pay an average of $4,846,

while those detainable as risks to the community under the PFA could pay

an average of $5,344 for release from jail.

So what are “detainable” offenses?

Under the PFA, police will maintain discretion to arrest and bring to

the station any individual who is charged with a crime and deemed a

threat to the public.

What’s new is that the law will create a presumption in favor of

pretrial release for any individual charged with offenses for which a

judge cannot deny pretrial release. That means officers are instructed

to cite and release lower-level offenders who, under the officer’s

discretion, are not deemed a threat to the community. They would be

given instructions to appear in court within 21 days.

Once an individual is arrested, prosecutors may petition the court for

pretrial detention. Once a judge receives that petition, their decision

to detain would hinge on whether the state has proven “by clear and

convincing evidence” that the defendant has committed a detainable

offense.

Detainable offenses include non-probationable forcible felonies such as

murder, aggravated arson, residential burglary, stalking, domestic

battery, offenses where the abuse victim is a family or household member

or if the defendant was subject to the terms of an order of protection,

gun offenses and several specified sex offenses.

Persons deemed to be “planning or attempting to intentionally evade

prosecution” may also be detained pretrial under what is called the

“willful flight” standard if they’ve been charged with a crime greater

than a Class 4 felony – such as property crimes, aggravated DUI and

driving on a revoked license.

[to top of second column]

|

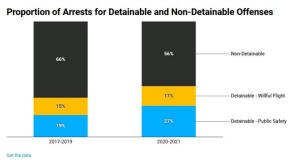

Research from the Loyola University of

Chicago's Center for Criminal Justice examines how arrests in recent

years would have been categorized under the Pretrial Fairness Act

that ends cash bail beginning Jan. 1, 2023. (Credit: loyolaccj.org/pfa)

Olson noted the detention standards create a greater likelihood that

individuals accused of domestic violence remain in jail than under

current law. That’s one reason domestic violence victim advocacy groups,

which helped craft the law, remain among its most ardent supporters.

“When we get to the domestic violence offenses, currently, they are

detained to a degree but most post bond within a relatively brief period

of time,” he said. “So it may be under the law that more of them stay in

pretrial detention for a longer period of time.”

How is judicial discretion limited by “non-detainable” offenses?

Under the PFA, there are no offenses that would be non-detainable in

every circumstance. Even misdemeanors and other low-level offenses can

result in detention if the defendant is already on pretrial release,

probation or parole.

But for the most part, the law prohibits detention of individuals

accused of committing lower-level, non-violent offenses. Olson used the

example of vandalism, criminal trespass where the defendant is not

deemed a threat, “someone stealing a six pack of beer,” small-amount

felony drug possession or low-level retail theft offenses.

There are many levels of nuance to detainability, Olson added. For

example, he noted, a homeless person who steals a purse might not be

detained on robbery charges because it would be difficult to prove them

to be a risk of willful flight. But an armed robbery with a firearm

would be a detainable offense under the dangerousness standard.

“Most arrests in Illinois are for relatively minor crimes,” he said.

“It's not the crimes that get much attention from the media or the

public, but most arrests are for relatively minor crimes. And so the

idea is divert those from the formal trappings of this process that take

time and resources.”

Olson noted judges in many counties will have more options for setting

release conditions for all defendants come Jan. 1 when the Illinois

Supreme Court launches its Office of Statewide Pretrial Services in

about 70 counties that don’t currently offer such services.

Pretrial services and supervision can range from sending reminders about

court appearances, to mandating monthly check-ins to confirm a

defendant’s address, to providing transportation, to overseeing

individuals placed on electronic monitoring.

Supervision may also include court orders for counseling or treatment

programs and requiring face-to-face reporting to a pre-trial service

officer.

Why not give judges greater authority to detain all individuals?

A frequent argument against the PFA from prosecutors and Republicans is

that the new detainability standards are too limiting for judges. Some

have requested Illinois implement a system similar to one adopted in New

Jersey in 2017 which allows judges to detain even for misdemeanor

crimes.

They’ve also argued that the standard for proving willful flight is too

high and some sections of the new law are contradictory, creating wider

categories of “non-detainable” offenses than the bill’s drafters

intended.

Olson noted the question of where to draw the line on judicial

discretion is important because of the finality of pretrial detention

under the new system.

“Now, the stakes are a lot higher, right?” Olson said. “The decision to

detain is a decision to detain, it's not a wishy-washy on-the-fence of

well, ‘We're going to hold you but if you can come up with $1,000,

you're free.’ This is a decision about freedom. And so I think with that

the argument by many is that detention should be more constrained.”

By providing lower-level offenders with a citation and scheduling them

to appear in court within 21 days, Olson said, the intent of the law is

to allow officers to go back to the beat rather than booking an

individual, and to allow the courts to spend more time on cases where

violence was involved or was likely to be involved.

It’s also something that, research has shown, has already been happening

more frequently since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

Olson said the first hearing for cited-and-released individuals would be

brief and would not focus on an individual’s detention, although a judge

could set conditions of pretrial release or pretrial supervision.

What could change about the new law before Jan 1?

Judicial discretion is a matter that could be reconsidered when

lawmakers return to the Capitol on Nov. 15.

A follow-up bill sponsored by former prosecutor and current Democratic

Sen. Scott Bennett, of Champaign, would, among other things, widen

judicial authority to allow for detention of a defendant charged with

any crime if the court believes they are a serious risk of skipping

trial, pose a danger to the community, or are likely to threaten a

potential witness or juror.

That’s a bill that Gov. JB Pritzker has said could be a launching point

for discussions as lawmakers consider amendments to the PFA, although he

has not endorsed all of its components.

The bill’s House sponsor and domestic violence victim advocacy groups

have pushed back against that specific provision, arguing that it would

overburden the court system and divert resources from more serious cases

where a person’s freedom is on the line and they’re accused of violent

crime.

Olson agreed that by expanding detainable individuals from roughly half

of those arrested to all individuals entering the system, the intent of

the law would be drastically changed by the proposed amendment.

Will those held in lieu of bail on Jan. 1 be freed under the PFA?

Nothing in the bill says that will happen, although opponents of the PFA

have cited its silence on the matter as a point of concern. Pritzker

said he would like it made explicit in a follow-up bill that individuals

held in lieu of bail when the bill takes effect will not be released.

Capitol News Illinois is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news

service covering state government. It is distributed to more than 400

newspapers statewide, as well as hundreds of radio and TV stations. It

is funded primarily by the Illinois Press Foundation and the Robert R.

McCormick Foundation.

|