Chilling audio provides glimpse into abuse at state-run facility

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[October 11, 2022]

By BETH HUNDSDORFER [October 11, 2022]

By BETH HUNDSDORFER

Capitol News Illinois

MOLLY PARKER

Lee Enterprises Midwest

Note: Article contains content and language

that may be offensive to some.

ANNA, Ill. — The disturbing 911 call began

with sounds of a struggle, then a voice that sounded like a child’s

cried out, “Let me go.” When the police dispatcher in the rural southern

Illinois community announced herself, no one responded.

She heard other voices, laughing and taunting, then a female voice said,

“You want me to break your other finger?”

There was shouting, and someone crying “Let me go” at least a dozen more

times.

At one point the victim — who was later identified as a 22-year-old

resident of the Choate Mental Health and Developmental Center — said “I

don’t like you.”

“I don’t give a shit,” a woman responded.

Almost five minutes passed on the June 2020 call before the dispatcher

got the attention of someone on the other end of the line. Then the

connection went dead.

With the audio recording in hand, the Illinois State Police launched an

investigation. They learned that the call was made as Choate employees

attempted to restrain a patient: A smart watch jostled in the struggle

had accidentally dialed emergency services. They discovered that the

voice heard pleading for help belonged to Alijah Luellen, who has

Prader-Willi syndrome, a genetic condition that can cause severe

childhood obesity, intellectual disability and behavioral problems. They

also discovered that the other voices belonged to the employees paid to

care for him.

Nonetheless, such incriminating evidence was not enough to hold anyone

accountable.

Such failures of accountability at Choate, which is run by the Illinois

Department of Human Services, do not begin or end with the 911 call.

Reporting by Lee Enterprises Midwest, Capitol News Illinois and

ProPublica reveals a culture of cover-ups that makes it harder to reform

the 270-bed developmental center for people with intellectual and

developmental disabilities and mental illnesses. In dozens of cases,

records show that Choate employees have lied to state police and to

investigators with IDHS’ Office of the Inspector General; walked out of

interviews, plotted to cover up or obfuscate alleged abuse and neglect;

and failed to follow policies intended to protect the integrity of

investigations.

The findings follow stories by the three news organizations last month

that exposed abuses patients have suffered at Choate. In response to

those articles, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker issued a warning to state

workers: Put an end to “awful” abuses or the state may be forced to shut

the facility down.

IDHS did not dispute any of the news organizations’ findings, and it

said in a statement that the agency requires employees to cooperate with

OIG investigations and trains them on the need to be truthful with both

the OIG and state police. Similarly, IDHS trains staff on preventing and

reporting abuse and neglect on at least a yearly basis.

But as the 911 incident reveals, cleaning up the facility’s practices

may not be easy.

When police questioned several of the employees on shift that night,

they all told the investigators that they believed it had been a routine

restraint, something they did to Luellen several times a week. One

worker also said the order for strapping Luellen to his bed was made

after the patient was “verbally uncooperative” and reached for the shirt

of an employee who told him he couldn’t stay up and watch TV after 10

p.m., according to the police report. Records show he remained in

restraints for two hours. During a medical examination after the

incident, a doctor found tenderness in his finger and bruises on his

upper body.

The investigators played the audio recording of the 911 call to each

employee and wrote down their reactions. According to notes from their

interviews, one worker acted nervous and told them all the shouting was

making her anxious; another told them he wished that they didn’t have

the audio because it “sounds bad.”

Yet they all claimed they couldn’t recognize the voice of the worker who

threatened the patient on the 911 call.

In addition, two employees cut their interviews with investigators short

and walked out. (Law enforcement cannot compel employees to answer

questions, according to state police; IDHS said that employees’

participation in criminal investigations is not mandated as a condition

of employment.) Another employee, in internal paperwork, initially

stated he assisted in the restraint. He later told police he had

falsified the paperwork and wasn’t actually in the room, according to

the police report.

The victim’s statement also wasn’t helpful in making the case: Because

of Luellen’s severe speech impediment, state police investigators asked

him to write down the initials of anyone who hurt him. He returned to

them a page of illegible scribbles.

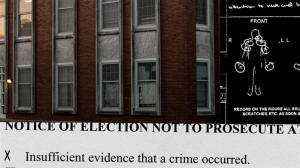

This June, two years after the incident, the Union County prosecutor

declined to bring charges, citing insufficient evidence. State police

interviewed six mental health technicians and one nurse who were working

on the unit that night. Two of the mental health techs who participated

in restraining Luellen were trainees; one was fired and the other

resigned. Two permanent employees have been on paid administrative leave

since the incident. None of the permanent employees were fired. The

nurse who ordered the restraints left Choate in December 2021 and

accepted a new job with the Illinois Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Reporters obtained a copy of the 911 call by making a Freedom of

Information Act request to Union County and provided the agency a copy

of the recording and questions about their handling of the case. But

when asked about the recording, the agency spokesperson said senior

officials had not listened to the 911 call and that it couldn’t be

released to them because it was part of an ongoing OIG review. That

review could lead to discipline against employees.

Benita Hunter, Luellen’s aunt and legal guardian, also received the

recording from reporters; hearing it for the first time left her stunned

and heartbroken.

“They’re supposed to be there to support and help the clients that they

have coming in,” Hunter said. “Alijah, he wouldn’t be able to explain

everything because of his developmental delays, and they know that. He

cannot defend himself and speak against them.”

Elusive Justice

While audio evidence of abuse is rare, the actions taken by Choate staff

in the aftermath of the investigation were not.

The OIG cited Choate employees in more than four dozen cases between

2015 and 2021 for lying or providing false statements to OIG

investigators; for failing to report an allegation within four hours of

its discovery, as is required by law; and for other failures to follow

department policy concerning the reporting and investigation of abuse

and neglect, according to an analysis of OIG records by the news

organizations.

Of the 1,180 allegations of abuse and neglect made during that time

frame, OIG ruled that only a tiny fraction were substantiated — meaning

that it found credible evidence to support the allegation. But records

and interviews make clear that investigatory missteps and lack of

employee cooperation can quickly derail an investigation.

Stacey Aschemann of Equip for Equality, a disability rights legal aid

organization that officially monitors the facility for the state, said,

“We commonly observe that no staff saw or heard anything, which is

unlikely.”

She added, “We have reason to believe that there are multiple cases that

would have been substantiated if additional evidence had been

available.”

In an interview, Union County State’s Attorney Tyler Tripp said he was

disturbed by the 911 recording in which Luellen was threatened. He was

also troubled by the fact that he couldn’t make a case. He kept it open

for two years, he said, hoping someone would come forward with more

information.

It’s not the only case in which he has encountered stonewalling that has

made prosecution difficult.

“In these types of situations, a select group of bad actors coordinate

in anticipation of an investigation to get their stories straight, to

obscure evidence and to frustrate the investigation,” Tripp said.

He said investigations are typically stymied if patient testimony is not

corroborated by employee witnesses. In addition, he said, some patients

aren’t even able to tell police what happened. Nearly 15% of residents

at Choate have a developmental disability that is diagnosed as severe or

profound, and about 10% are nonverbal.

Another case from the same year that has languished on Tripp’s desk

involves a resident who alleges a Choate employee wrapped a towel around

the patient’s neck until he passed out, according to two people who are

intimately familiar with the investigation but not authorized to comment

on it. A different staffer discovered the patient unconscious with a red

mark on his neck.

The accused employee denied the accusation and refused an interview by

police. Other employees claimed they didn’t know what happened.

Tripp has yet to make a decision on whether he will press charges, and

he declined to comment on the details of the case. He said that in

general, when he delays a decision, it’s because an investigation has

brought forth some evidence but not as much as is needed to successfully

prosecute a case.

Though uncooperative facility staff had long frustrated state police

investigations, administrators became the target of an investigation in

January 2020. It started when two employees reported that they witnessed

a colleague, Kevin Jackson, remove his belt and repeatedly use it to

whip a female patient. The employees, who worked in a neighboring

building, reported that they saw the assault through the victim’s

bedroom window.

After an OIG investigator notified state police of the allegation

against Jackson, assistant administrators Teresa Smith and Gary Goins

looked at the investigatory file and then sent a psychologist to speak

with the patient while the police were still on their way, according to

then-security chief Barry Smoot, in his testimony before a Union County

grand jury. After the police arrived, the victim said that someone other

than Jackson had hit her.

[to top of second column]

|

Alex Bandoni/ProPublica (Source Images:

Whitney Curtis for ProPublica and an Illinois State Police case

file)

Longstanding OIG policy had prohibited administrative involvement in

abuse and neglect investigations to avoid conflicts of interest.

According to Smoot, facility director Bryant Davis also accessed the

file, along with Smith, on a different occasion. And state police Sgt.

Rick White testified before a Union County grand jury that the

administrators’ interventions were unusual and threatened to derail the

investigation, court records show.

Jackson, the mental health tech, pleaded not guilty to a felony battery

charge and his case is pending. The administrators were also initially

charged with felony official misconduct; the state’s attorney withdrew

those charges but left open the possibility of filing new ones.

Senior department officials have defended the actions of the Choate

administrators. Attempts to reach the administrators for comment,

including facility director Davis, were not successful. Jackson declined

to comment.

State Sen. Terri Bryant, a Republican from Murphysboro whose district

includes Choate, said she was alarmed by the department’s handling of

this case. Shortly after the reported assault, Bryant said, she received

a call from a worker informing her that employees had placed paper over

the windows on the unit where the incident occurred.

Bryant said she went to see it for herself, then called an IDHS

administrator in Springfield to inquire about it. He called the facility

and was told the paper had been taken down. He relayed that information

to Bryant. But Bryant said she was sitting outside the building when he

called her back and could see from her car that it was still up. In

August, 20 months after the assault, the paper was still there.

An IDHS spokesperson said, “At times, paper was on windows because the

window fixtures were on order. The paper would have been for privacy in

resident bedrooms.”

Few Consequences

Serious consequences in cases of abuse and misconduct are rare. The

Illinois State Police opened at least 40 investigations at Choate over

the past decade. Of those, 28, including Luellen’s case, did not result

in any criminal charges, with the Union County prosecutor most

frequently citing insufficient evidence as the reason for not moving

forward. The other 12 investigations resulted in felony charges against

26 employees, with most pleading guilty to misdemeanor charges or having

their cases dismissed entirely. (A few are pending.) Only one employee

was convicted of a felony — for hiding evidence, rather than for the

underlying abuse. To date, no one has served prison time.

Beyond the lack of criminal sanctions, employees are also rarely fired

for misconduct, including actions that obstruct investigations.

According to a review of records where OIG cited Choate for problems, by

far the most common response to the deficiencies cited was a

recommendation for “retraining.” The response was included in cases

where OIG cited employees for lying or otherwise impeding an

investigation. One former official at Choate said the department’s

retraining amounted to providing employees with a policy document and

having them sign a form saying that they’d read it.

In one 2016 case, Choate planned a training for the entire staff that

addresses “late reporting of abuse/neglect, staff members encouraging,

bribing or coercing individuals regarding OIG investigations and

obstruction with an ongoing OIG investigation,” IDHS records show. The

department redacted details about what prompted the retraining.

In 25 cases, the department acknowledged a need to retrain workers in

how to treat Choate’s clients with “dignity and respect.” IDHS’ policy

for employees demands that they do not engage in dehumanizing practices,

such as cursing, yelling, mocking or other cruel treatment.

Though the details of incidents were redacted in most of these cases,

employees have been cited by OIG in recent years for using racist,

homophobic and derogatory language toward people with disabilities,

including calling them “retards.”

Code of Silence

C. Thomas Cook, who has worked with people with developmental

disabilities for more than 50 years across four Midwestern states,

including Illinois, said that it’s not uncommon for employees in large

facilities like Choate to close ranks and protect one another in the

face of abuse allegations.

When the code of silence is deeply entrenched, Cook said, it takes far

more than retraining to change the culture. Things like cameras and

monitors can help, Cook said, but employees also need to know that they

will face strict sanctions, including criminal charges and dismissals,

if they cover for abusive colleagues.

“There are ways to disrupt that code of silence,” Cook said. “It’s the

responsibility of the people who run the programs to do it.”

It's especially problematic, he said, in communities where the employees

are part of a tightly knit population with a common interest in

protecting each other.

That characterization could perfectly describe the facility in rural

Anna, a town with a population of about 4,200. Reporters identified

numerous instances in which investigations involved two or more suspects

who were relatives, friends or in romantic relationships with one

another, according to the police records.

In one case, a Choate social worker offered to help police interview

patients during an abuse investigation, but then police discovered she

was the girlfriend of the technician who was the target of the

investigation. Two recently charged employees are relatives of the

current acting security chief, whose job is on the front line of

investigations. He declined to comment. This August, a senior IDHS

official grew concerned enough about the familial relationships between

security officers and the employees they were investigating that he sent

an email to select staff reminding them of the need to recuse themselves

to avoid even the appearance of a conflict of interest, emails obtained

by reporters showed.

When a facility is critical to a struggling local economy, Cook said,

that can compound the incentives to cover up misconduct. Choate serves

the poorest part of the state, and the facility has been Union County’s

largest employer for decades. A former administrator once told The

Southern Illinoisan that if Choate wasn’t there, “Anna would dry up and

probably blow away.” The facility has employed generations of the same

families, including that of longtime Anna Mayor Steve Hartline, whose

mother and father worked there while he was growing up.

Hartline went on to serve for decades as head of security at Choate,

where his officers were the first line of inquiry when there was an

allegation of patient mistreatment. Hartline said he believed the

scrutiny resulting from the recent staff arrests has given Choate an

unfair bad rap; he rejected the premise that employees were protecting

each other.

“There’s no such thing as a code of silence at Choate. If there is

something found, such as a broken policy, it’s duly noted and dealt with

by administration and labor relations,” he said.

But Hunter, Luellen’s aunt, said that it was upsetting that the

employees who threatened and mocked her nephew did not face serious

consequences for their behavior. Luellen has since moved to a different

state-run center about 100 miles north. But during the more than two

years the young man lived at Choate, Hunter said she believed staff

restrained him too often and failed to teach him skills to manage his

behavior. Every time she spoke with staff, “they promised that he was

getting the utmost care,” she said. “But my heart and my spirit was not

telling me that he was actually receiving that from them.”

*****

The Numbers Behind Choate’s Cover-Up Culture

Between 2015 and 2021, the Office of the Inspector General for the

Illinois Department of Human Services received 1,180 allegations of

abuse and neglect at Choate. But late reporting, uncooperative

employees, lack of video evidence, conflicting witness accounts and

other investigatory missteps can result in the OIG being unable to

obtain enough evidence to substantiate an allegation — even when there

are unexplained patient injuries.

We requested these records, but OIG refused to send them all, citing

state law that prohibits the release of details from unsubstantiated

cases. They did send a stack of information from that same time period

regarding substantiated cases, along with records from 184 cases in

which the OIG identified problems and asked Choate administrators to

respond with their plans for remedying the situation. These are cases in

which OIG flagged serious issues, although they may not have had enough

evidence to support the allegation.

The files they sent are a record of Choate’s required responses. Most of

them were heavily redacted, but they offered a window into some of the

problems OIG investigators face at Choate:

• In 29 cases, Choate administrators acknowledged that employees failed

to follow department policy concerning the reporting and investigation

of abuse and neglect.

• In 11 instances, Choate employees failed to report an allegation of

abuse or neglect within four hours of discovery, as the law requires.

• In nine cases, the OIG found that employees lied or provided false

statements to investigators.

• In more than one-third of the 184 cases where the OIG asked for a

response, the only recommendation from Choate officials was to “retrain”

employees.

• In 14 cases, employees were discharged, terminated or suspended.

Ultimately, the OIG revealed that over the seven years for which we

requested data, it was only able to substantiate 48 cases — roughly 4%.

This article was produced for

ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Lee

Enterprises,

along with Capitol

News Illinois. |