More U.S. companies charging employees for job training if they quit

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[October 17, 2022] By

Diane Bartz [October 17, 2022] By

Diane Bartz

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - When a Washington

state beauty salon charged Simran Bal $1,900 for training after she

quit, she was shocked.

Not only was Bal a licensed esthetician with no need for instruction,

she argued that the trainings were specific to the shop and low quality.

Bal's story mirrors that of dozens of people and advocates in

healthcare, trucking, retail and other industries who complained

recently to U.S. regulators that some companies charge employees who

quit large sums of money for training.

Nearly 10% of American workers surveyed in 2020 were covered by a

training repayment agreement, said the Cornell Survey Research

Institute.

The practice, which critics call Training Repayment Agreement

Provisions, or TRAPs, is drawing scrutiny from U.S. regulators and

lawmakers.

On Capitol Hill, Senator Sherrod Brown is studying legislative options

with an eye toward introducing a bill next year to rein in the practice,

a Senate Democratic aide said.

At the state level, attorneys general like Minnesota's Keith Ellison are

assessing how prevalent the practice is and could update guidance.

Ellison told Reuters he would be inclined to oppose reimbursement

demands for job-specific instruction while it "could be different" if an

employer wanted reimbursement for training for a certification like a

commercial driving license that is widely recognized as valuable.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has begun reviewing the

practice, while the Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission have

received complaints about it.

The use of training agreements is growing even though unemployment is

low, which presumably gives workers more power, said Jonathan Harris who

teaches at the Loyola Law School Los Angeles.

"Employers are looking for ways to keep their workers from quitting

without raising wages or improving working conditions," said Harris.

The CFPB, which announced in June it was looking into the agreements,

has begun to focus on how they may prevent even skilled employees with

years of schooling, like nurses, from finding new, better jobs,

according to a CFPB official who was not authorized to speak on the

record.

"We have heard from workers and worker organizations that the products

may be restricting worker mobility," the official said.

TRAPs have been around in a small way since the late 1980s primarily in

high-wage positions where workers received valuable training. But in

recent years the agreements have become more widespread, said Loyola's

Harris.

One critic of the CFPB effort was the National Federation of Independent

Business, or NFIB, which said the issue was outside the agency's

authority because it was unrelated to consumer financial products and

services.

"(Some state governments) have authority to regulate employer-driven

debt. CFPB should defer to those governments, which are closer to the

people of the states than the CFPB," it added.

[to top of second column] |

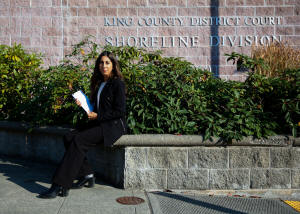

Licensed esthetician Simran Bal, who was

taken to court by her former employer to repay $1900 in trainings

they required her to attend, poses for a portrait outside the King

County District Court in Shoreline, Washington, U.S., October 13,

2022. Bal, whose case was dismissed, says she was already licensed

for services the trainings covered. REUTERS/Lindsey Wasson

NURSING AND TRUCKING

Bal said she was happy when she was hired by the Oh Sweet salon near

Seattle in August 2021.

But she soon found that before she could provide services for

clients, and earn more, she was required to attend trainings on such

things as sugaring to remove unwanted hair and lash and brow

maintenance.

But, she said, the salon owner was slow to schedule the trainings,

which would sometimes be postponed or cancelled. They were also not

informative; Bal described them as "introductory level." While

waiting to complete the training, Bal worked at the front desk,

which paid less.

When she quit in October 2021, Bal received a bill for $1,900 for

the instruction she did receive. "She was charging me for training

for services that I was already licensed in," said Bal.

Karina Villalta, who runs Oh Sweet LLC, filed a lawsuit in small

claims court to recover the money. Court records provided by Bal

show the case was dismissed in September by a judge who ruled that

Bal did not complete the promised training and owed nothing.

Villalta declined requests for comment.

In comments to the CFPB, National Nurses United said they did a

survey that found that the agreements are "increasingly ubiquitous

in the health care sector," with new nurses often affected.

The survey found that 589 of the 1,698 nurses surveyed were required

to take training programs and 326 of them were required to pay

employers if they left before a certain time.

Many nurses said they were not told about the training repayment

requirement before beginning work, and that classroom instruction

often repeated what they learned in school.

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters said in comments that

training repayment demands were "particularly egregious" in

commercial trucking. They said firms like CRST and C.R. England

train people for a commercial drivers license but charge more than

$6,000 if they leave the company before a certain time. Neither

company responded to a request for comment.

The American Trucking Associations argues that the license is

portable from one employer to another and required by the

government. It urged the CFPB to not characterize it as

employer-driven debt.

Steve Viscelli, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania who

spent six months training and then driving truck, said the issue

deserved scrutiny.

"Anytime we have training contracts for low-skilled workers, we

should be asking why," he said. "If you have a good job, you don't

need a training contract. People are going to want to stay."

(Reporting by Diane Bartz; Editing by Chris Sanders and Lisa

Shumaker)

[© 2022 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]

This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|