Astronomers document a not-so-super supernova in the Milky Way

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[February 02, 2023]

By Will Dunham [February 02, 2023]

By Will Dunham

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Supernovas are not always so super. These

explosions that mark the death of a star often are spectacularly

energetic. But once in a while they are a complete dud.

Scientists on Wednesday detailed one of the duds - a massive star that

had so much of its material siphoned off by the gravitational tug of a

companion star in a stellar marriage called a binary system that by the

time it came to explode at the end of its life cycle it could barely

manage a whimper.

Its eventual explosion was so tame, in fact, that the collapsed star -

now an incredibly dense object called a neutron star - remains in a

docile circular orbit with its companion. A more powerful explosion at

the very least would have resulted in a more oval-shaped orbit and even

could have sent the star and its companion hurtling in opposite

directions.

This binary system, studied using a telescope at the Chile-based Cerro

Tololo Inter-American Observatory, is located about 11,000 light years

from Earth in our Milky Way galaxy in the direction of the constellation

Puppis. A light year is the distance light travels in a year, 5.9

trillion miles (9.5 trillion km).

The neutron star's mass is about 1.4 times that of our sun, having

previously been 12 times more massive than the sun. Its companion star

boasts a mass 18 to 19 times greater than the sun after cannibalizing

its mate. The two stars orbit around each other every 59-1/2 days,

separated by about eight-tenths of the distance existing between Earth

and the sun.

The anemic stellar explosion that did occur was called an

"ultra-stripped" supernova. These happen when a massive star collapses

as it runs out of fuel in its core, but cannot manage a strong blast

because a companion star has sucked off much of its outer layers and

removed material that otherwise would be violently ejected into space.

[to top of second column]

|

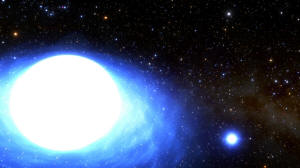

An undated illustration shows the binary

star system CPD-29 2176, located about 11,000 light years from

Earth. NOIRLab/National Science Foundation/AURA/J. da Silva/Spaceengine/Handout

via REUTERS

"Since there is little material in the stellar envelope, there is

almost no ejecta from the shock of the collapse," said Arizona-based

astronomer Noel Richardson of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University,

lead author of the study published in the journal Nature.

Study co-author Clarissa Pavao, an Embry-Riddle undergraduate

student studying physics, described the explosion as: "Faint, subtle

and passive."

"If there was more of an explosion, the orbit would not be

circular," Richardson said. "A normal supernova wouldn't necessarily

destroy the companion, but could disrupt the orbit a lot more. It

could, for example, give a kick to the system that either makes the

orbit much more elliptical or even sends the surviving star and the

neutron star on fast trajectories in opposite directions with speeds

that could even send them out of the galaxy."

The type of binary system examined in this study is rare, with

roughly 10 estimated to exist in a Milky Way populated by about

100-400 billion stars.

Unlike the lonely sun, perhaps half of our galaxy's stars reside in

binary systems. Scientists have pondered whether planets capable of

harboring life exist in such systems, as depicted, for example, with

"Star Wars" character Luke Skywalker's home planet Tatooine.

"We know of some systems that are binaries with planets, but these

are harder to confirm, and all of these are for stars with masses

like our sun," Richardson said. "In the case of these massive stars,

we have not yet detected planets around them. The stars weigh so

much more and are more luminous than sun-like stars, making the

planet detection more difficult than around the smaller stars."

(Reporting by Will Dunham, Editing by Rosalba O'Brien)

[© 2023 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |