Problems with abuse, neglect and cover-ups at Choate extend to other

developmental centers in Illinois

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[July 12, 2023]

By MOLLY PARKER

Lee Enterprises Midwest

& BETH HUNDSDORFER

Capitol News Illinois

This year, Illinois officials announced what seemed like a solution to

the outcry over abuse and cover-ups at a state-run developmental center:

Downsize the facility and move about half the residents elsewhere. Some

of the roughly 120 relocated residents of the Choate Mental Health and

Developmental Center would receive care in community settings. Others

are expected to end up in one of the six developmental centers located

in other parts of the state. This year, Illinois officials announced what seemed like a solution to

the outcry over abuse and cover-ups at a state-run developmental center:

Downsize the facility and move about half the residents elsewhere. Some

of the roughly 120 relocated residents of the Choate Mental Health and

Developmental Center would receive care in community settings. Others

are expected to end up in one of the six developmental centers located

in other parts of the state.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker and Illinois Department of Human Services Secretary

Grace Hou said the plan would “reshape the way the state approaches care

for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

But a new investigation by Lee Enterprises Midwest, Capitol News

Illinois and ProPublica has found that the problems at Choate extend to

the other centers as well. People with developmental disabilities living

in Illinois’ publicly run institutions have been punched, slapped, hosed

down, thrown about and dragged across rooms; in other cases, staff

failures contributed to patient harm and death, state police and

internal investigative records show.

The Illinois State Police division that looks into alleged criminal

wrongdoing by state employees investigates more allegations against

workers at these seven residential centers than it does at any other

department’s workplaces, including state prisons, which house far more

people, according to an analysis of state police data.

It has opened 200 investigations into employee misconduct at these

developmental centers since 2012 — most of them outside of Choate.

The state’s seven developmental centers, home to about 1,600 people, are

situated from the bottom of the state at the edge of the Shawnee

National Forest all the way north to the Wisconsin border. The oldest

operating facility opened in 1873 and the newest one in 1987. They house

dozens, and in some cases hundreds, of people with developmental

disabilities in a hospital-like setting. These residents have a range of

conditions: genetic, acquired from a problematic birth, or resulting

from exposure to dangerous chemicals or from injury in childhood or

adolescence.

As in other states, many of these facilities were built in small towns

and rural areas. Today, they are short-staffed and at times chaotic and

dangerous, according to a slew of reports and interviews with workers

and advocates. This May, the safety concerns inside the developmental

centers prompted a court-appointed monitor to urge IDHS to stop placing

anyone covered by an expansive consent decree into any of the agency's

developmental centers.

“Too many residents suffer physical injury, sexual assault and death to

regard placement in such facilities as safe,” wrote Ronnie Cohn, the

monitor and a New-York based expert on disability services, in a report

that was prepared at the behest of a federal judge in ongoing

proceedings.

Illinois is a stubborn outlier among states, continuing to funnel huge

sums of money into institutional care. Many others have entirely

shuttered or significantly downsized their state-run institutions.

Illinois has about the same number of people living in them as do

California, Florida, New York and Ohio combined. In Illinois, the

lawsuit that led to the 2011 consent decree argued that the state had

violated the civil rights of people with developmental disabilities by

failing to offer enough options for community-based care. The next year,

the state closed one of its centers and tried to shut another; that

effort, to shutter the Murray Developmental Center in southern Illinois,

failed in the face of union and community pushback. Now, the state is

making space for 60 more residents at Murray, some of which will likely

transfer from Choate.

“This is one of the most backwards states in the nation on everything we

know how to measure when it comes to the care of people with

developmental disabilities,” said Allan Bergman, a consultant from

suburban Chicago who advises clients and governments across the U.S. on

disability policies and programs.

We asked IDHS about the new reporting on issues within the state’s

developmental centers. Agency spokesperson Marisa Kollias pointed out

that the state had announced a broader review of every facility that

IDHS operates as part of its response to the reporting on Choate. She

said in a statement that the state has worked to “identify the root

causes of misconduct” and correct them. Among recent improvements, IDHS

has appointed a new chief safety officer, held numerous trainings on how

to report abuse and neglect and ordered more than 400 security cameras

for installation across all of its facilities by the end of the year,

she said.

Additionally, IDHS acknowledged shortcomings in the community care

settings that operate under the agency’s oversight. Kollias said that

the community system had been financially neglected by the prior

administration and noted that Pritzker’s administration has successfully

advocated for millions of dollars in new spending for these programs.

Funding for home- and community-based care has roughly doubled what it

was when Pritzker took office to more than $1.7 billion, though

advocates contend it’s still not enough after years of steep cuts.

State Police Investigations Rise

State police investigations of claims against staff at Illinois’

developmental centers are on the rise: Nearly 70% of them over the past

decade were initiated since 2019, the year Pritzker took office.

Of the 200 state police investigations into employee misconduct over the

past decade, 161 pertained to allegations of physical abuse and criminal

battery; 25 to allegations of sexual assault and custodial sexual

misconduct; and 10 to alleged criminal neglect of residents. Four were

death investigations.

Of those cases, 22 led to convictions, almost all of them for abuse.

A spokesperson for the state police said the agency could not speak to

the reasons for the increase or for the disparity in the volume of cases

from IDHS facilities that it handled in recent years as compared with

Illinois Department of Corrections prisons or other agency workplaces.

But Kollias, the IDHS spokesperson, said the department views the

increase in state police investigations “as an improvement in

accountability at the facilities.” She also noted that most cases did

not lead to convictions.

Both the numbers and interviews show how difficult it is to pursue

charges, even when investigations get underway. In the facilities

outside of Choate, between 50% and 99% of residents have disabilities

that are diagnosed as “severe and profound”; some of those individuals

are nonverbal and unable to communicate in traditional ways.

Investigative records show instances of employees failing to report

abuse or working together to hide it, or a general reluctance on the

part of state employees to share information with investigators. Even

when there’s a conviction, state police investigators are not always

able to fully determine what happened.

For instance, among the more recent physical abuse cases where a

conviction was secured is one from Shapiro Developmental Center in

Kankakee, a small industrial city on the outskirts of suburban Chicago.

In 2020, a patient was found with U-shaped markings and dark bruising on

his chest, back, arms, legs and genitals.

A nurse examined his injuries but dismissed them as a rash from

medication. A physician who examined him the next day had a different

take: She believed the markings were consistent with someone striking

the patient with an object, such as a belt or cord. The U-shaped

markings looked like they could have been from a belt buckle, she told

investigators.

Police interviewed multiple employees who worked the night shift, but

they offered little information. The patient was unable to provide

police specific details of the incident. He was only able to tell them a

female worker “beat the hell” out of him on the night shift by striking

his genitals with an unknown object.

The patient’s treatment plan notes that he needs help managing behaviors

that include irritability, agitation and outbursts. One employee

admitted to police that she had slapped the patient across the face that

evening after she had directed the patient to stop a problematic

behavior and he told her to “shut up, bitch.” But the worker denied she

was responsible for any of his more serious injuries. No one else came

forward with any information.

The worker pleaded guilty last year to misdemeanor battery and received

12 months of court supervision. She was fired from Shapiro, but neither

state police nor IDHS’ inspector general were able to determine the

cause of the patient’s more extensive injuries.

Peter Neumer, the IDHS inspector general, said his department regularly

encounters cover-ups at facilities across the state, which prompted him

to push for a new legal measure enhancing the penalty options against

those who attempt to stonewall or obfuscate investigators. Pritzker

recently signed it into law.

The state police reports are not the only cause for concern. The

inspector general receives and investigates all allegations of resident

abuse and neglect. Some of those result in recommendations for civil

penalties against employees, up to termination, and suggestions to

address systemic failures. The most serious cases, where criminal

misconduct is alleged, are also passed on to the state police.

Between 2013 and 2022, the inspector general investigated nearly 4,000

allegations from the developmental centers — with the most recent five

years seeing a 45% increase in allegations compared with the earlier

part of the decade.

[to top of second column]

|

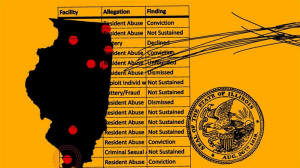

Credit: Alex Bandoni/ProPublica. Source

Images: Reporters’ notes and the Illinois state government.

There are also safety concerns documented in records from the

Illinois Department of Public Health, which responds to complaints

because it is responsible for ensuring compliance with Medicaid and

Medicare regulations.

These records show that in addition to the abuse cases, residents

have suffered from life-threatening mistakes and oversights by

employees.

At Mabley Developmental Center, in the small north-central Illinois

town of Dixon, a patient drank from a bottle of toilet bowl cleaner.

The inspector general found that a worker had neglected the patient,

who died of cardiac arrest three days later.

At Ludeman Developmental Center in Park Forest, in south suburban

Cook County, a resident who was supposed to be closely supervised

left the facility without permission and was later found walking

barefoot across a busy six-lane street. In a different elopement

case, a Ludeman resident suffered hypothermia after he went outside,

unbeknownst to staff, one early fall morning when the temperature

was in the 30s, wearing only a diaper and sat in the wet grass.

At Kiley Developmental Center in Waukegan, on the Wisconsin border,

staff locked a disruptive patient in his room using a bedsheet tied

across his door, an unauthorized form of restraint, according to

health department inspection records. That same facility

accidentally allowed an employee who the inspector general had

previously found had abused a patient to return to work for two

months before anyone noticed, according to staff interviews with

health department surveyors. The worker has since been fired,

according to a statement from IDHS.

Critical Staffing Shortages

This rise in allegations of violence and neglect comes amid

significant staffing shortages, leading employees to work

unsustainable and potentially dangerous overtime hours, according to

an analysis of overtime records and interviews with more than a

dozen employees at four facilities.

As of February, about 200 employees at developmental centers

statewide — about 5% of the workforce — were unable to perform the

job they were hired for pending the outcomes of abuse and neglect

allegations with the state police or inspector general’s office.

Most of them were on paid leave, including some who had been on paid

leave in excess of two years. Others had been reassigned from their

regular duties, and a small number had been suspended without pay

pending the outcome of criminal court cases against them.

Neumer, the inspector general, said his office has prioritized

working through cases more quickly to reduce the amount of time

employees are out on leave. But in cases involving law enforcement,

the inspector general cannot proceed with its internal investigation

until a criminal case concludes, he said. Some cases linger for

years with state police or prosecutors’ offices.

The staffing issues go well beyond those who are being disciplined.

Across the state, about 570 jobs at developmental centers — more

than 14% of positions — are unfilled.

AFSCME Council 31, the union that represents most workers at these

24/7 facilities, issued a report in December criticizing the state’s

use of forced overtime to address chronic understaffing and raising

alarms about its impacts on workers and residents.

In at least one case at Kiley, staffing shortages may have

contributed to a patient’s death.

In February 2022, an individual with a known swallowing disorder was

supposed to be closely monitored while eating. But on this day, a

worker went home sick, leaving her unit short-staffed. While no one

was watching, the resident choked and died, according to a report by

the Illinois Department of Public Health. A worker told public

health investigators that records were fabricated at a supervisor’s

request to make it look as though the facility had provided proper

supervision.

The inspector general’s investigation into the incident is ongoing,

and the employees who were involved remain on leave. IDHS said in a

statement that in response to the health department’s findings,

Kiley staff received training on “providing sufficient direct care

staff.”

That was the second time in two years that a patient at Kiley with a

known swallowing disorder choked to death while eating unsupervised.

In a 2020 case, according to a report by the inspector general, the

man may have been dead for several hours before anyone noticed and

called for help.

Kollias, the IDHS spokesperson, said that staffing shortages in

health care are a nationwide problem and that the state has taken

steps to more quickly fill positions. Contract staff are filling in

at every center to ensure required staffing levels for each shift

are met, she said.

Conditions Are “Beyond Dire”

In some of those facilities, employees have raised alarms to their

higher-ups, as a security chief at Choate had done before the state

took action to address problems there, email records obtained under

a Freedom of Information Act request to IDHS show.

This January, Matt Comerford, a Mabley employee, sent an email to

Hou, the IDHS secretary, seeking her immediate attention to

conditions he described as “beyond dire.” In his letter, he said

that patient injuries — including black eyes and, in one case, an

open head wound that required 13 staples — could not be accounted

for, and he accused staff, including administrators, of stonewalling

investigators.

“It has become normal for staff to never seem to know anything about

these injuries,” wrote Comerford, the facility’s business

administrator. He concluded his letter by saying that he believed

speaking out put his livelihood at risk. “But the risks of not

speaking out are far too great for me to remain silent.”

Mabley’s clinical services director, Patricia Fazekas, a longtime

employee who resigned in May, wrote about similar concerns in an

“exit” survey obtained by the news organizations.

“The system is broken and they know if they complain they will be

retaliated against,” she said of staff. If one were to visit Mabley,

they would “witness abused and neglected individuals being cared for

by verbally abused and neglected staff.”

In March, James Zarate, an assistant director at Kiley, emailed a

different senior IDHS official, telling her that residents’

well-being was in jeopardy in that facility, as well. Kiley staff,

he wrote, are receiving “little guidance or training” and the

facility is “operating with a shortage of staff which is being

exacerbated by a toxic work culture.” Six other Kiley employees, who

spoke with a reporter on the condition that their names be withheld

because they still work there, similarly expressed that staffing

issues and mismanagement had created a problematic work environment

that put residents and employees at risk of harm.

The department said that the concerns the employees raised in their

emails were passed on to the appropriate oversight bodies, and that

IDHS is “independently investigating the claims and will address

issues fully and appropriately.”

Both Comerford and Zarate, who do not know each other, faced

disciplinary action shortly after sending their emails and

additional complaints to various oversight bodies.

The department said the disciplinary decisions it made against the

employees were unrelated to their emails and complaints. Zarate, a

new hire, was terminated as a “probationary discharge” after six

months on the job. His final performance review said he had failed

to perform his job duties satisfactorily, such as by not ensuring

that staff completed tasks in a timely manner or seeking input from

his superiors. He was specifically admonished because subordinates

had reported to health department surveyors that a staffing crisis

resulted in residents not receiving “active treatment.”

“Mr. Zarate has made this an acceptable response when not meeting

expectations, resulting in a possible IDPH citation,” the

performance review stated.

The department didn’t dispute that staffing challenges exist, but in

a statement to the news organizations, it said such a response was

problematic because “essential services are expected to be provided

to residents despite staffing challenges.”

Zarate declined to speak for this article.

Comerford was placed on paid administrative leave for 10 weeks, then

suspended for 20 days without pay. Paid leave, the department said,

is not punitive. As for the suspension, a disciplinary letter from

the department said Comerford had, among other alleged infractions,

raised his voice and cursed during a meeting and took a call on his

private cellphone. The department said he had, on multiple

occasions, displayed conduct unbecoming of a state employee and

failed to perform job duties in an accurate and timely manner.

In a statement, Comerford said that “a well-worn page of the DHS

Mabley playbook is to discredit and defame those who address

systemic injustices against the most vulnerable population.” He said

that the department had lied about, exaggerated or taken out of

context many of the circumstances that led to the claims against

him. The department said Comerford had the ability to challenge the

discipline and did not do so. “He served his disciplinary time and

has returned to work,” IDHS said in a statement. |