Fossils show ancient long-necked sea beast's 'gruesome' decapitation

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[June 21, 2023]

By Will Dunham [June 21, 2023]

By Will Dunham

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - In shallow waters about 242 million years ago, a

strange marine reptile built unlike any other animal ever on Earth

hunted for fish and squid, using an inordinately elongated neck to

ambush prey. Suddenly and violently, its life ended - decapitated by a

powerful predator.

Scientists for two centuries have suspected that prehistoric marine

reptiles like this one, named Tanystropheus, possessing very long necks

were highly vulnerable to such attacks. A fresh examination of

Tanystropheus fossils unearthed in Switzerland decades ago on a mountain

called Monte San Giorgio has provided the first unambiguous evidence to

demonstrate it.

The researchers studied neck and head remains of two species of

Tanystropheus, detecting bite marks and other signs of trauma indicating

decapitation. The larger species, the one that ate fish and squid,

reached 20 feet (6 meters) long, though this individual was about 13

feet (4 meters). The smaller species was about 5 feet (1.5 meters) long,

with teeth indicating a diet of soft-shelled invertebrates like shrimp.

The neck of Tanystropheus was three times longer than its torso. Useful

in hunting, extreme neck elongation was common among marine reptiles

spanning about 175 million years during the age of dinosaurs. But this

came with a price: an obvious weak spot for predation.

There was evidence of predation in the fossils of both species. One has

two tooth-shaped punctures and a tooth scratch. The other has a pit

caused by a tooth hitting the bone. Both bear bone injuries where the

neck was severed.

"These very dramatic examples of predator-prey interaction are extremely

rare in fossils, and they give us an insight into how these animals

lived together. It reminds us that these creatures went through dramatic

events similar to what we see in nature today - in this case in a

particularly vivid and gruesome way," said paleontologist Stephan

Spiekman of the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart in Germany,

lead author of the research published this week in the journal Current

Biology.

The attacker of the bigger Tanystropheus species likely was a large

marine reptile, the researchers said, perhaps a species of:

Cymbospondylus, 33 feet (10 meters) long; Nothosaurus, 23 feet (7

meters) long; or Helveticosaurus, 12 feet (3.5 meters) long.

[to top of second column]

|

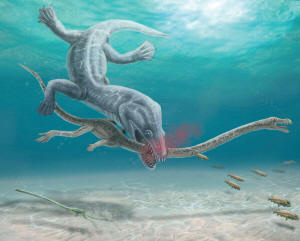

An undated artist's rendition of a

marine reptile predator attacking and decapitating the long-necked

marine reptile Tanystropheus hydroides during the Triassic Period.

Roc Olive (Institut Catala de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont)/FECYT/Handout

via REUTERS/File Photo

Various marine reptiles or predatory fish, they said, could have

decapitated the smaller species.

Tanystropheus, appearing during the Triassic Period at a time of

evolutionary innovation following Earth's worst mass extinction,

thrived across the northern hemisphere for 10 million years. It was

a distant relative of the dinosaurs, which first appeared roughly

230 million years ago.

"We think Tanystropheus spent most of its time in the water, staying

in the shallows, using its small head and long neck to ambush prey

from the sea floor," Spiekman said.

Its neck was composed of 13 elongated vertebrae, almost cylindrical

and hollow. Despite a marine existence, Tanystropheus lacked certain

swimming adaptations, with limbs resembling lizards or crocodiles

rather than flippers and no tail fluke. Its wide skull had

upward-facing nostrils like modern crocs.

"Tanystropheus is so interesting because its body plan is entirely

unique in the history of all of life. Sure, there are other animals

with a very long neck, but not a neck that is this long, this stiff

and this lightweight, with very long, string-like neck ribs. And

then what adds to the weirdness and mystery is that the rest of the

animal is also puzzling," Spiekman said.

It shows how evolution can be a game of trade-offs.

"The long-necked reptile might not realize that it is being attacked

until it is too late, especially if the predator comes from its back

and thus the small head is very far away. All in all, long-necked

marine reptiles were able to overcome this weak spot, likely because

the long neck had more advantages," said State Museum of Natural

History Stuttgart paleontologist and study co-author Eudald Mujal.

(Reporting by Will Dunham, Editing by Rosalba O'Brien)

[© 2023 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |