|

Gillette Ransom of the Elkhart Historical Society

introduced Sternberg.

Sternberg owns the Starhill Forest Arboretum and has

written three tree books with his most recent being Native Trees of

North America from the Rockies to the Atlantic.

As Sternberg began his lecture, he said that trees affected by

emerald ash borers (EAB) generally die. There are few natural

predators of ash borers currently present in North America. When it

comes to emerald ash borers, black ash and green ash trees are

especially affected because the borers love them and white ash is

not far behind.

The blue ash tree is not closely related to green and black ash

because blue ash has a different metabolic and structural system.

Sternberg says that is a point in its favor. Blue ash is the main

species on Elkhart Hill and there are several very old blue ash

trees at the Elkhart nature preserve which have not been affected by

ash borers.

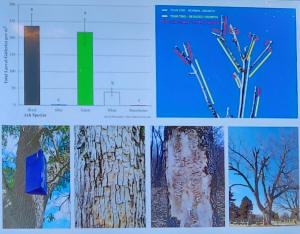

Sternberg showed photos of various ash trees. The

markings show the EAB infestation. If the problem is caught early,

these trees can be saved. Looking at the condition and size of the

growth from year to year is important. If the growth has slowed,

Sternberg said you better do something soon if you desire to save

the tree.

Early on, Barney traps (so-called because of their purple color) on

trees were used to track the spread of the invading insect. The

traps were something that Sternberg says won’t kill any significant

number of ash borers but can confirm their presence.

When looking at ash trees, Sternberg said shorter

annual twig growth, branch die-back and “D” shaped holes indicate

problems. This creates a bleaching, a pale colored appearance of the

bark in these areas. Woodpeckers can hear EAB munching on the trees

and will remove outer bark in an attempt to get at the larvae.

Sternberg said that alone does not solve the problem but gives us

one piece of the puzzle.

Where ash tree bark has already sloughed off, back and forth

squiggles tracks on the trunk show where emerald ash borers have

taken out the tissue of the tree. Sternberg said the tree is

basically dead by that point.

Questions Sternberg said you should ask are do you want to save the

tree? Is it worth saving? How large is it? Will you commit to

treating the tree for the foreseeable future either annually or

periodically?

If you decide to treat the tree Sternberg said is important to know

that the cost of treatment versus removal of the tree is about

equal.

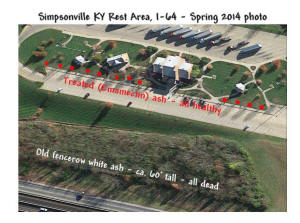

Along with many others, Sternberg has been working to

save ash trees. Some years ago, while he was driving through

Kentucky, Sternberg found an old highway right-of-way full of dead

white ash trees. But there was one survivor tree, which can be

useful for resistance breeding. A nearby rest area had many trees

that were being treated and all had survived.

Information from Michigan, Ohio and Kentucky, where blue ash is much

more common than it is here in Illinois, suggests that some of these

trees might be able to survive the emerald ash borer.

What Sternberg has found is that in the bluegrass

country of Kentucky, where limestone soils are well suited to blue

ash, observations have found that roughly 40 percent of the trees

that had been healthy when the borer arrived were still alive as the

pest population began to crash after about 10 to 12 years due to

loss of their food source.

The goal for Elkhart Hill was to bring as many of the ancient trees

there as possible into that 40% category with a one-time treatment

funded by private donations. In a three-week media blitz, Sternberg

said “we found so many generous people who agreed with that goal

that we were able to raise $14,000.” They realized no one in the

country had tried to do a media blitz like this one to help with the

problem.

Here is the story:

In April of 2021 on Elkhart Hill someone inspected the nature

preserve with Sternberg and they found a couple of dead ash trees

along the exposed edge of the area. They were not leafing out, but

many others were. The goal established for Elkhart hill was to

reinforce as many ancient trees as possible to preserve them until

biological controls could take over.

May 23, 2021, Sternberg and others began doing an Elkhart tree

inventory. He said they could do a certain number of inches in

diameter based upon the amount of money they had raised and were

looking at how many trees there were and how big they were. The

group wanted to save some of the best trees, the medium sized trees

still in good shape, and ones that had room to grow. They also

wanted to have some un-treated control trees to see if they also

would survive. After an initial walk through, the group started

measuring and marking trees, compared notes, and added GPS locations

and photos to find them later.

Sternberg said they had to get permissions and regulations from

Elkhart Hill Grove Nature Preserve (a private owner) and the

Illinois Nature Preserve Commission to comply with nature

preservation policies.

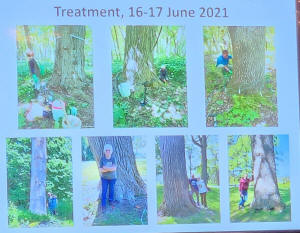

To treat trees Sternberg said they used Emamectin

Benzoate, which cost more than $500 a bottle. On June 16 and 17,

2021, treatment began with injecting thirty-two big blue ash trees.

They also arranged for eager adjacent landowners to have their own

trees treated.

On May 21, 2022, there was an Elkhart hill lightning strike at the

end of a stormy research tour. Sternberg said it was less than 100

feet from where he was standing, shook the ground, and created a

deafening sound and blinding light. At that point they left the

grove of trees for safety reasons. In October 2022 Sternberg and

others went back and found the two ash trees that had been struck by

lightning. They were blown apart, but one was still sprouting.

In fall of 2021, Sternberg and others began to gather

seed to grow seedlings and establish a new cohort (a successive

generation) of trees at the Elkhart nature preserve. Sternberg said

the team gathered local provenance seeds from female trees in

Elkhart. Some of the blue ash trees on Elkhart Hill are old enough

to predate the Revolutionary War. [to top of second

column] |

Next, they had them propagated (which is not easy) at

a commercial plant nursery in Missouri and grew them into small

seedlings for planting in the nature preserve in spring of 2023.

Donations were collected to raise money for the new trees and

several volunteers helped with the planting.

All of it was done with permission and assistance

from landowners and participation by the Illinois Nature Preserves

Commission.

Sternberg said they started with only thirty-two small trees grown

from local provenance, but if those trees mature, they will create a

new generation of this rare forest species.

When working on a nature preserve Sternberg said you

do not want to mix with the genetics of the preserve because it

contaminates what is already there.

When planting the trees in the preserve, they created open sky for

the seedlings by removing some existing groups of surplus sugar

maples. Deer resistant barriers were built using twigs and branches

from the downed maples on site, so no foreign wood or metal was

introduced to the preserve and no plantings from other areas were

brought in.

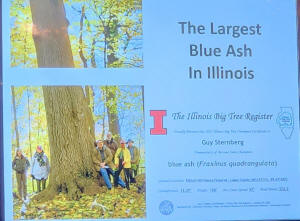

Elkhart Hill was also found to have had the largest

Blue Ash (fraxinus quadrangulata) in Illinois, making it the new

state champion for this species on the Illinois Big Tree Register.

To do tree breeding for future resistance Sternberg says you should

harvest seeds and scions from survivor trees of any affected ash

species for future resistance breeding.

The National Ash Tree Seed Collection Initiative is one organization

trying to collect trees for preservation. A brochure they have put

out says: “America is losing its ash trees at an alarming rate. An

invasive species, the emerald ash borer, has already destroyed

millions of ash trees.”

Because of that, “the loss of all of America’s ash

trees is a real possibility. An effort is underway to gather seed

from populations of native ash tree species nationwide.”

The initiative is asking people to assist in the effort by

collecting ash tree seeds and sending them to the Rose Lake Plant

Materials Center in East Lansing, Michigan.

When collecting seeds, the National Ash Tree Seed Collection

Initiative says to collect at least 500 seeds from each population

and check that seeds are filled. When mature the “seed is typically

brown to tan in color and separates easily from the tree.”

Once you have collected seeds, they should be put in a cloth or

paper bag and stored in cool, dry conditions until you are ready to

ship them. Do not put them in a plastic bag.

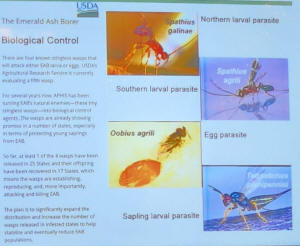

Though emerald ash borers continue to be a problem

Sternberg says they're hoping to have biological controls. The USDA

says, “there are four known stingless wasps from the emerald ash

borer’s native countries that will attack either EAB larva or eggs.”

The USDA Agricultural Research Center is currently evaluating a

fifth wasp.”

In an article on Biological Control, it says, “for several years

now, APHIS has been turning EAB’s natural enemies—these tiny

stingless wasps—into biological control agents. The wasps are

already showing promise in a number of states, especially in terms

of protecting young saplings from EAB.”

At this point, at least one of the four stingless wasps has been

released in 25 (infested) states. The offspring of these wasps have

been recovered in 17 states. The USDA says it shows “the wasps are

establishing, reproducing, and, more importantly, attacking and

killing EAB.” Additional good news for central Illinois is that a

wasp release has just been approved for public land in the Lincoln

area this year!

The plan is “significantly expand the distribution and increase the

number of wasps released in infested states to help stabilize and

eventually reduce EAB populations.”

As Sternberg says, we need to find ways to preserve what we do have.

In finishing his talk, Sternberg expressed thanks to all the people

made it possible.

One question was about treatments such as drenching a tree’s base

and why it is not effective on large trees.

The problem is uptake and longevity. Sternberg said

if you are mixing up a soil drench to pour around the base of a tree

to let roots absorb, you are counting on the roots absorbing enough

to go up through the entire tree and out to the leaves. You are

counting on that happening at a time when the beetles are starting

to reproduce.

When using the basal drench system Sternberg said that must be done

every year and he would only recommend it for small trees. Larger

trees cannot absorb enough of the insecticide to reach all of the

way up the tree. In the next year, the treatment would have to be

done again.

Sternberg said mechanized infusion treatments with

Emamectin chemicals kill what larvae is in the entire tree. The

process is expensive and invasive but it can last for up to three

years because the chemical goes straight through the tree and acts

both as an insecticide and a deterent.

With the parasitic wasps someone asked how hopeful he was that they

would begin to make a dent in the problem. She wanted to know the

long range prognosis for using these wasps.

For a while, Sternberg said we will need to keep treating other ash

trees to get them past the surge of the emerald ash borer. Sternberg

said people need to continue to protect trees. As wasps kill borers

and the wasps reproduce, it will create a balance so there are not

as many borers around that will overwhelm a tree. Hopefully

woodpeckers will continue to adapt to feeding on the larvae and

other controls will increase as well.

When it comes to the National Seed Collection

initiative someone asked whether it applies to just to blue ash or

all ash trees. Sternberg said the collection initiative applies to

all native ash species.

Sternberg was also asked when the ash tree seeds mature. He replied

the seeds mature in early fall.

A final question was about the growth rates of ash trees.

Sternberg said that if healthy they can grow a foot or more each

year.

The next Elkhart Historical Society dinner lecture will be held

Friday, June 23 at 5:00 p.m. at the Wildhare Café in Elkhart.

Reservations can be picked up at the café and must be turned in by

June 16.

The speaker will be Professor Tony Rothering of Lincoln Land

Community College. Rothering is an official bird bander. Recently,

he was in Elkhart and was able to catch and release 120 different

birds after banding, measuring and recording them. Rothering will

explain what is going on with our climate and what it is doing to

migration patterns we have been able to observe through the years.

Ransom said Elkhart is an oasis for migrating birds.

[Angela Reiners]

Related information:

Guy Sternberg

www.StarhillForest.com

Rose Lake Plant Materials Center

USDA-NRCS 7472 Stoll Road

East Lansing, Michigan. 48823

Telephone: 517-641-6330

Email: john.lief@mi.usda.gov

(If possible, email Lief after sending seeds)

|